The Hon. Mark Wolf has had to make many difficult decisions in his long career. As a U.S. District Court judge he required the FBI to divulge that James (Whitey) Bulger was a top-echelon informant. He sentenced Salvatore Di Masi, the former Massachusetts Speaker of the House, to eight years in prison for extortion and fraud. And he became the state’s first judge in 50 years to sentence a man to death, ordering the execution of serial killer Gary Lee Sampson in 2003.

But the decision to come to Martha’s Vineyard every summer for the past several decades? That hasn’t taken much deliberation at all.

“The Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis said he could do twelve months’ work in eleven, but not in twelve,” Judge Wolf recalled from the back porch of the no-frills cottage he rents every July off Main street in Vineyard Haven. “And about 25 years ago, that became my philosophy too.”

Earlier this summer, a man who has spent most of his illustrious career sitting alone behind the bench, reflected on the multigenerational group of friends he has built as a summer resident of Martha’s Vineyard. It is a group that has not only enriched the month he spends on the Island every year, but has had an indelible influence on the 11 months he spends elsewhere.

In a line that has resonance for many regular visitors to the Vineyard, Judge Wolf said, “At home, we have a lot of friends. But on Martha’s Vineyard, we have a community.”

As the 2019 summer comes to a close that community, centered around the area once known as Writers Row in Vineyard Haven, has by now dispersed around the country. But it is clear that Judge Wolf and his compatriots not only leave their mark on the Vineyard, but that the Vineyard has helped to shape them — as authors, businessmen and women, civil servants, lawyers, journalists — and as a judge.

“The Vineyard has really helped sustain me,” Judge Wolf said. “Being a judge can be a lonely endeavor. And this is a place where I’ve been very comfortable developing friendships with a wide range of people, and renewing them year after year.”

A graduate of Yale who went on to Harvard Law School in the early 1970s, the young man who grew up idolizing defense lawyer Perry Mason on television decided that he wanted a career in public service, only on the other side of the bar. He worked for Deputy U.S. Attorney Laurence Silberman during the Nixon administration, and was there to watch the American president resign during the Watergate proceedings.

“It was quite an extraordinary experience,” he recalled. “And that gave me exposure to a range of issues, including how do you hold the highest officials accountable for criminal conduct in our democracy? I developed an enduring interest in that, which led me to be chief public corruption officer in Boston, and then later, a federal judge.”

During that time, he also began to get his first taste of the Vineyard. He and his wife, Lynne, came to the Island in 1972 after learning about it from his college classmate, Sam Pease, a longtime summer resident. Starting in 1977, they returned regularly.

At the age of 38, he was appointed by President Reagan to the U.S. District Court in Massachusetts, the second youngest judge in commonwealth history to take the federal bench.

Over the next 30 years, he oversaw a number of high-profile cases, including the mafia trials that led to the prosecution of New England mob boss Raymond Patriarcha Jr. and Vincent Ferrara. But probably the most notorious case of his career came in the late 1990s, when he held hearings that revealed the FBI’s corrupt relationship with two organized crime figures, Stephen (The Rifleman) Flemmi and Whitey Bulger.

Judge Wolf began writing his decision for the Bulger case in 1999. By the end of June, he still hadn’t finished. He wasn’t going to let that stop him from spending July on the Vineyard.

“Of course, I was working with some highly confidential documents,” he recalled. “They had the names, for example, of people who were FBI informants against the mafia. If that ever got disclosed, those people would be in grave danger.”

Maintaining secrecy was paramount. A United States marshal who lived on Cape Cod would bring the documents over by ferry early every morning. A state police trooper would pick her up and drive her to Judge Wolf’s house at 10 o’clock, where she would give him the sealed files. The judge would work on them until early afternoon, when the state trooper would pick up the marshal and bring her back to the ferry. The routine repeated itself throughout the month, until Judge Wolf had finished his 661-page decision that determined the FBI was complicit in murders committed by Mr. Bulger and Mr. Flemmi, but that Mr. Flemmi could not be prosecuted with the information he provided as an informant. Mr. Bulger remained a fugitive, with an enormous bounty on his head. The case cut deeply into the law enforcement community.

Although not entirely.

“About the only good thing that came of the Bulger case was that the marshal married the state policeman,” Judge Wolf said. “That was truly a marriage made on Martha’s Vineyard.”

Judge Wolf’s eldest son Jonathan also found love on the Vineyard. Bored and looking for a job as a teenager, his father nudged him to volunteer at Camp Jabberwocky. There he met his future wife Mandy Adams. Lynne Wolf was chairman of the board of directors for Camp Jabberwocky when the young couple was married there 10 years ago, with campers as many of the officiates.

“It literally changed his life,” Judge Wolf said.

The Vineyard has changed Judge Wolf’s life too. It’s mostly what he wants to talk about. He’s keen, serious and careful with his words when discussing cases. But when discussing the Island, his hands creep above the table, his eyes come alive, and he becomes effusive about the only place that has allowed him to focus on docks rather than dockets, motion rather than motions, brunches rather than benches.

Every morning on the Island, he wakes up and plays tennis at the Vineyard Haven Yacht Club. It was there, at his court away from court, that he met Tod Sedgwick, who in 2009 Judge Wolf swore in as the U.S. ambassador to Slovakia. The ceremony took place on his Vineyard front porch. Nearly a decade later, Judge Wolf has gone to the country four times to speak about and fight international corruption, a cause which he now devotes himself to since taking senior status as a judge in 2013. His NGO, Integrity Initiatives International, aims to create an international anti-corruption court that will hold kleptocratic governments in check.

“The Vineyard community is the foundation of Integrity Initiatives,” Judge Wolf said.

When he’s not working, Judge Wolf spends time with his friends on the Island. That includes dinners with contemporaries like Bill and Lia Poorvu and Chuck and Nancy Parrish. One friend in particular stands out.

“I count my days on the Vineyard in roses,” Judge Wolf quipped. “The more times I encounter Rose Styron, the better.”

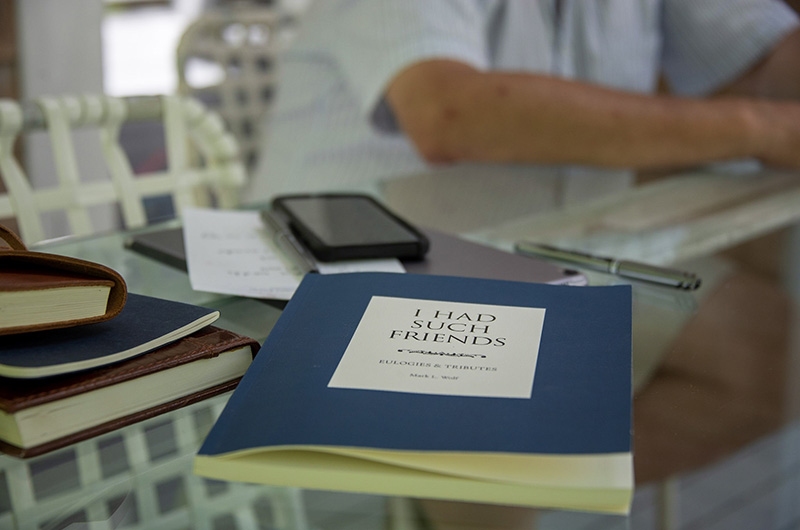

It also includes trips to the cemetery to visit generations now gone. He has a self-published anthology of eulogies that he has given for Art Buchwald, Bill Styron, his “fratello” Luciano Rebay, and others. Almost all include poetry.

Every year, he and his wife throw a Fourth of July party on the Island. It has since become a tradition to read the Declaration of Independence during the festivities. Last year, he presided over a series of immigration cases in which he determined that Immigration and Customs Enforcement was illegally deporting aliens married to citizens. He said he couldn’t have made that decision without his time on the Island, and in particular, those annual readings.

“This country was founded with a declaration of human rights,” he said. “Reading the declaration every year on the Vineyard influenced me to look at those immigration cases not just as really challenging legal questions, but in the context of the history of this country, and what it aspires to be.”

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »