Jessie Benton’s comfortable summer home in Chilmark was just a shack on a windy hill when her parents, the painters Thomas Hart Benton and Rita Piacenza, bought it in 1923.

It was her mother who discovered the Vineyard first, in 1919, Ms. Benton said in an interview at her home last week. “She came here because she heard there was a colony of deaf mutes in Chilmark.”

An Italian immigrant, Ms. Piacenza had learned English from a Scotswoman and wound up with a brogue that mortified her, Ms. Benton explained. On the Vineyard, she learned to communicate in signs.

“She wanted to paint and go barefoot and not have to be embarrassed when she spoke — she could just use the hand language,” said Ms. Benton, who also learned the local signs for milk and eggs when she was old enough to shop at the Chilmark Store.

The shack Ms. Piacenza rented for her first Island summer was on the same property she and Mr. Benton would purchase a few years later after marrying in 1922.

“In back of it was a barn with a hayloft where my brother slept,” said Ms. Benton, who was born 13 years after her brother Thomas Piacenza (T.P.) Benton. “I slept in the closet.”

By the time she came along in 1939, Ms. Benton was the only child in wha t was becoming a summer colony of artists and intellectuals, where her father’s fishing buddies were the actor James Cagney and artists Denys Wortman and Steve Dohanos. “There were these famous, famous people that we didn’t even know were famous,” she recalled. Like Somerset Maugham, who stayed with the Bentons years before she would discover, in a college classroom, that he was a prominent author. With T.P. — who’d had Jackson Pollock for a babysitter — now far too old to play with a little girl, Ms. Benton had no playmates until a British family with young boys settled in a nearby barn to wait out the war.

“That was my first friend,” she recalled. A triple portrait by Alfred Eisenstadt shows her at about age six, flanked by her English friend and a cousin, their small faces alight.

“I’m very dressed because I have my shoes on,” she said. “I insisted on shoes and socks for the photograph.”

The summer colony was one big family for Ms. Benton, who would make the rounds to visit neighbors every day.

“There was a sense of belonging to everyone who lived here too,” she said. “It didn’t matter which mother would take care of us. We all took care of each other.”

Now surrounded by woods, the neighborhood three quarters of a century ago was a mostly treeless landscape of sheep and cow pastures, with expansive views that persist in Ms. Benton’s memory.

“We could see water all the way to Quitsa,” she said.

From one point on the property, Ms. Benton said, “you could see the whole (Menemsha) pond and the cut and the Coast Guard station.” All those vistas are now gone, along with the livestock that terrified her as a child.

“I was deathly afraid of cows,” she recalled. “I needed to piggyback to the beach every day.” Electricity and running water didn’t come to the neighborhood until well after the end of the war, during which Ms. Benton remembers the blackout curtains that covered windows by night so light from the family’s kerosene lanterns could not offer a target to offshore German forces.

In war and peace, the Bentons made their way to Chilmark every summer, first from New York city and later from Kansas City, Mo. In his studio, now a guest house, Mr. Benton painted for more than 50 seasons. Many of his works hang in the home today, including The Butterfly Catcher. One of the paintings he created for his daughter’s birthday every year, on a theme of her suggestion, this one from her 10th is not Ms. Benton’s favorite.

“I was very disappointed,” she said. “The other disappointment for a birthday painting was the one of the seven animals coming to my [seventh] birthday, because I had visions of Walt Disney kind of animals, really cute little bunnies and squirrels, and instead they were Daddy’s kind of elongated, very scary animals and ducks . . .

“I still don’t like the painting very much.”

A musician as well as a painter, Mr. Benton was an accomplished harmonica player who invented a form of written notation to transcribe classical compositions for harmonica.

“Daddy was a really good musician. The Hohner harmonica people used his notations,” Ms. Benton said.

“I think if he was a better musician, he would have been a musician instead of an artist, to tell you the truth. Plus you can see music in the way he paints, especially in the earlier stuff,” she continued, citing her father’s dramatic 1934 canvas The Ballad of the Jealous Lover of the Lone Green Valley.

The Bentons’ regular home music nights — “we called them sings” — were commemorated on a 1942 78-rpm record that is now available online.

“Decca Records made Saturday Night at Tom Benton’s because every Saturday night we had music,” Ms. Benton said.

“There was music always in this house, and so of course both my brother and I became musicians.”

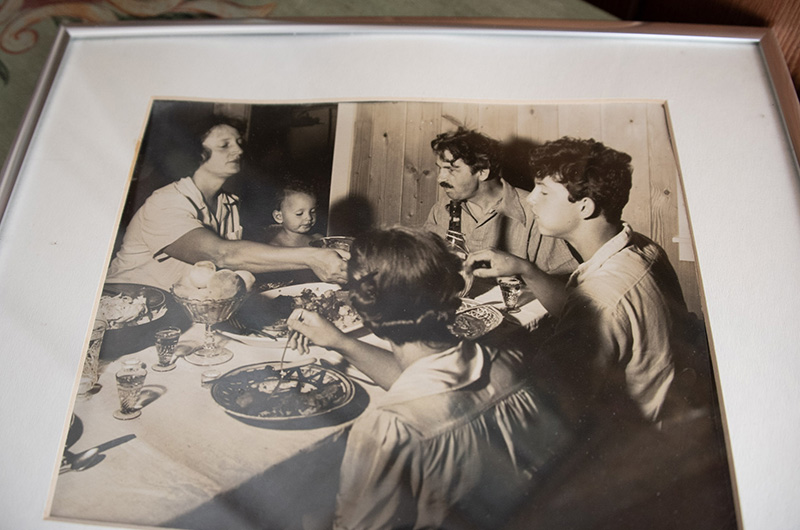

As a baby, Ms. Benton appears to be gumming the harmonica in a framed photograph of the Benton and Gale Huntington families playing music on the Vineyard in the early 1940s. But when she grew older, she chose the guitar as her instrument.

“I was a folk musician,” she said. Her father’s famous portrait, Jessie With Guitar, hangs in her Chilmark living room not far from the piano where she learned to play her first song — She’ll Be Coming Round the Mountain — from Ruth Crawford Seeger.

Next to the piano hangs a photograph of Ms. Seeger’s famous son Pete. Over the door there’s a photo of another musician, the late Mel Lyman.

While Ms. Benton is not a visual artist — “I can paint; I don’t paint,” she said — the family music tradition continues. Her husband Richie Guerin is a multi-instrumentalist and all three of their children, who live in the area, play as well. Last weekend, the guitarist Jim Kweskin dropped by the house to jam.

When they’re not at the house in Chilmark, Ms. Benton and Mr. Guerin might be working on one of the properties they own in Gay Head or Sandwich. In winter, they reside in the Hollywood Hills and Baja, Calif.

But Chilmark is the touchstone of their lives, where the wind and birdsong are the loudest sounds and the memories of Ms. Benton’s free-range, musical and often solitary childhood remain fresh.

“It was just a beautiful, beautiful time to be alone on Martha’s Vineyard,” she said.

Comments (6)

Comments

Comment policy »