July 8, 1671, was a great day for Thomas Mayhew. It was a bit more complicated for everyone else.

Summoned months earlier to Fort James, N.Y. by written decree of the Colonel Francis Lovelace, Mr. Mayhew had spent the past two years avoiding the jaunty new royal governor and emissary of the “Merrie Monarchy,” as Charles Banks described him in his history of the Vineyard.

A puritanical man with little regard for his revolving door of English (and Catholic) overlords, Mr. Mayhew was too busy converting Wampanoags to Christianty and buying up, parcelling and selling their land on Martha’s Vineyard to respond to Col. Lovelace’s supplicatory epistles.

By 1670, the Island, still very much a wilderness, had settlements of Great Harbor and Takemmy, with smaller outposts at Starbuck’s Neck in Edgartown, extending past Tower Hill toward Katama, as well as along the Edgartown Great Pond, West Tisbury and the Vineyard Haven harbor, according to historian and Martha's Vineyard Museum research librarian Bow Van Riper.

Industry was largely non-existent; most Islanders were farmers or subsistence fishermen.

Critically, significant Wampanoag settlements existed not only in Chappaquiddick and Aquinnah, but throughout the Island, at Farm Neck, on the southern end of the Lagoon, Tashmoo, Beach Bottom Cove in Tisbury Great Pond and significant chunks of Chilmark.

Mr. Mayhew ruled over it all with little or no colonial oversight or governing structure, a free man at the forefront of a new world.

But when an English merchant barque owned by a certain Mr. Richard Cutts of Portsmouth crashed in Vineyard waters, leaving a cache of good Barbados rum as its only survivor, the little lord Lovelace decided he’d had enough, requesting the immediate attention of Mr. Mayhew.

“Indeed, I did expect an Account of this accident from yorself,” Lord Lovelace wrote Mr. Mayhew in a Sept. 7, 1669 letter. When Mr. Mayhew ignored the letter, Col. Lovelace grew more forceful. “It is ordered . . . Mr. Mayhew . . . take a Journey hither,” minutes from a May 14, 1670 governor council meeting read. “The Governor intends to settle those Parts,” referring, of course, to Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket.

Thus, with his long-held freedom, and Island, at stake, the octogenarian Mr. Mayhew had little choice but to journey down to Fort James, his 23-year-old grandson Matthew in tow.

He didn’t know what to expect.

“For 30 years, since 1641, he had been responsible to none, and now he was facing a crisis in his affairs at the summons of an unknown master, set in authority over him by his ‘Dread Sovereign Lord,’ Charles the King,” Charles Banks writes in the first volume of his History of Martha’s Vineyard.

Mr. Van Riper put it more succinctly.

“Lovelace is the new sheriff in town,” he said. “And doubtless, Mayhew is thinking, oh crap.”

But Mr. Mayhew’s fears were unfounded.

The “roistering” and “Popish” colonial governor, as Banks called him — ironically the direct antithesis of the Puritans he was ordered to govern — was in fact quite satisfied with Mr. Mayhew’s work “reclayming and civilizing” the Wampanoags. So satisfied, that he ordered that Mr. Mayhew “dureing his naturall life bee Governor of the Island called Martin’s or Martha’s Vineyard, both over the English inhabitants, and Indians.”

And what was the price for Mr. Mayhew’s governorship for life?

“Six barrels of Merchantable Cod-Fish,” annually.

“Laus deo,” or “Praise be,” Mr. Mayhew wrote in a letter regarding the occasion.

“He says what anybody would say in that instance,” Mr. Van Riper explained. “Yes, your lordship. Very encouraged, your lordship.”

•

Exactly 350 years later, and the dramatic conference at Fort James is relevant less for Mr. Mayhew’s lifetime governorship — which lasted all of two years, when the Dutch retook New York from the English — but a different, more bureaucratic development that occurred on July 8, 1671.

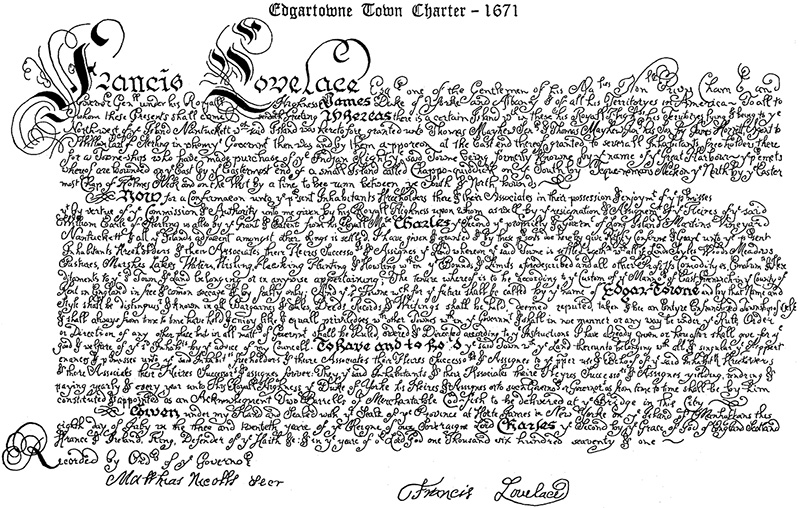

As part of Mr. Mayhew’s deal, Francis Lovelace officially incorporated Great Harbor and Takemmy with town charters, conferring on their inhabitants all the “privileges . . . granted them by enfranchizing them in town corporacon.”

The towns of Edgartown and Tisbury were thus born as part of New York Colony, fraternal twins that on Thursday this week celebrated their sesquarcentennial anniversaries. The Tisbury town seal still has the barrels and codfish required as recompense.

Edgartown will have a picnic at a still-undetermined date in September to honor the occasion. Tisbury’s celebration has yet to take shape.

“July 8, 1671 is significant not so much in the sense that either town was brought into existence as a social entity,” Mr. Van Riper said. “There were already clusters of people living there. Instead, 1671 is the ‘single ladies put a ring on it’ moment, where the governor charters two towns and creates . . . the political geography that will hold for two centuries.”

In exchange for the incorporations, Mr. Mayhew was granted the “Manor of Tisbury” under his feudal domain, which two decades later would later become Chilmark. It was likely one of the only feudal domains in New England.

“Mayhew comes back with the charters, he comes back with the governor for life thing, he takes a deep breath, and he goes, ‘Woohoo, I’m set, my authority over the entire Island has been confirmed.’”

For Mr. Mayhew, that meant substantial land and the power of judge, jury and executioner. For other white men, it led quickly to a failed rebellion by Simon Athearn, who balked at Mr. Mayhew’s governorship. Wampanoags were less lucky. They were required to “live quietly and peaceably with true submission to that authority wch now is sett over them,” Colonel Lovelace wrote, referring to the new governor. Sachems, or Wampanoag leaders, had to pay homage to their royal highness, and Mr. Mayhew was ordered to encourage them to make “Sewan” — likely wampum — jewelry, according to Charles Banks.

The establishment of colonial authority and town incorporation also accelerated the displacement of Wampanoags to the Island’s less arable fringes, a dark movement partially advanced by the power of the charters signed that fateful day.

“This moment is only about halfway through the process by which the English shoved the Wampanoags out to Chappaquiddick and Gay Head,” Mr. Van Riper said. “The process of the English takeover just continues to accelerate the next 50 years.”

•

While Mr. Mayhew is long dead, and only a few physical vestiges of his world remain, including the Vincent House behind the Whaling Church in Edgartown, according to Mr. Van Riper, and possibly the Hancock Mitchell Mayhew House in Quansoo, the political implications of the charters are still felt across the Island.

In the eons since the signing, Dukes County has become part of Massachusetts, Oak Bluffs has split off from Edgartown, West Tisbury split off from Tisbury, and English philanthropists, worried that the Wampanoags would have no land if settlement continued, set aside a small area in Aquinnah for their residence. Today’s balkanized political geography began with the chartered 1671 divisions, boundaries that are still shifting with the sands of time.

As for the charters themselves, those have also been partially lost to history.

Tisbury was only able to locate their original — a sepia, faded work of 17th century calligraphy — after the over-six-foot-tall town accountant, Jon Snyder, took a peek in the town vault, noticing it high above stacks of other historical arcana.

Edgartown was less successful, with town clerk Karen Medeiros unable to find the 1671 charter despite a Nancy Drew-like detective hunt, calling first the state of Massachusetts archives division and then New York, to no avail. By Thursday afternoon, Paulo De Oliviera at the Registry of Deeds had located a transcribed version of the document from 1764, thereby declaring that the land, and all its “woods, meadows, pastures, marshes, lakes, waters,” and “all other commodities” shall be known as Edgartown into the future.

A digital copy of the charter sat before a distraught Ms. Medeiros in her office on Thursday, the town vault wide open.

“I can’t seem to find the original,” the town clerk said. “But I will keep looking.”

Mr. Mayhew could be heard rustling in his Edgartown grave. Everyone else was just happy to no longer be part of New York.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »