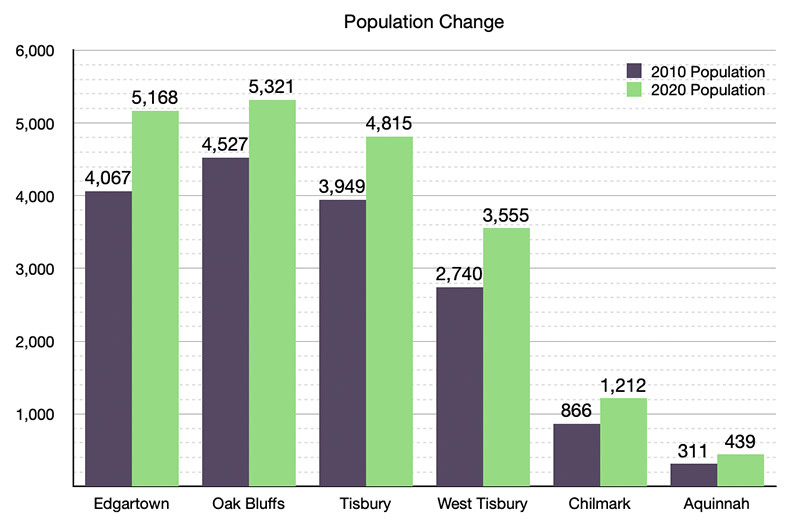

The University of Massachusetts Donahue Institute projected in recent population estimates that tiny Aquinnah would lose approximately 50 residents in the 2020 U.S. Census, bringing its population down to about 270 people.

In fact, the smallest town on the Island ballooned by a larger percentage than any other community in the state, rising from 311 people in 2010 to 439 people in 2020, an increase of 41 per cent.

“They predicted Aquinnah going down,” said Adam Turner, executive director of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission. “The degree and the nature of the census was way different than what had been projected. We’re happy that some of the numbers are laying out what’s really happening here.”

With long-awaited 2020 U.S. census data released last Thursday, the surprise jump in Aquinnah’s size played out similarly across the Island, showing a significant population increase in all six towns over the past decade.

Although unsurprising for local public officials, the dramatic growth codified in the Vineyard census bucked national trends, defied expert predictions and will have wide-ranging ramifications for the decade to come, increasing potential money from state and federal agencies and giving the Island a greater voice in its congressional districts.

The census also reflects a rapidly changing Vineyard — one that is becoming significantly more diverse and significantly more year-round, even as housing development slows and inventory evaporates.

But more broadly, the census finally puts a hard number on the wider demographic changes Island planners have been clamoring about for much of the past decade and earlier.

“The Island is growing,” Mr. Turner said. “It’s not a surprise . . . but it’s an entirely different look than what we saw in 2010. These things will lead to important discussions about public policy.”

According to the data, the year-round population of Martha’s Vineyard swelled by 24 per cent in the past 10 years, growing from 16,535 in 2010 to 20,600 in 2020.

Every down-Island town gained approximately 1,000 residents and saw double-digit population increases, ranging from an 18 per cent increase in Oak Bluffs to a 27 per cent jump in Edgartown.

Oak Bluffs, the largest town on the Island, grew from 4,527 in 2010 to 5,341 in 2020. Tisbury grew by 22 per cent, from 3,949 people in 2010 to 4,815 people in 2020. And Edgartown grew from 4,067 people in 2010 to 5,168 people in 2020.

Up-Island towns saw even larger changes in population.

Chilmark nearly rivaled Aquinnah, growing by 40 per cent — tied with Nantucket for the second largest percentage increase in the commonwealth — from 866 people in 2010 to 1,212 people in 2020. West Tisbury grew by 30 per cent, from 2,740 people to 3,555.

In an interview, county commissioner Keith Chatinover, who headed the Island’s complete count committee with support from commission planner Alex Elvin, praised results from the census, saying he saw 19,000 as the “over-under” for year-round population numbers.

Hitting the 20,600 mark, Mr. Cahtinover said, showed the results of a year of hard work from counters, public officials and volunteers who knocked on doors and campaigned to promote census awareness.

“I was really excited,” Mr. Chatinover said. “We’ll get more money, and be a bigger player in state districting.”

Coming just weeks after the Covid-19 pandemic hit, the decennial census was an effort to count the number of people living or staying in a given location as of April 1, 2020. Although exact figures remain elusive, data from the Steamship Authority, voter registration and elsewhere indicate that several thousand additional people moved to the Island full-time over the past year.

“If we had the 2021 census, we would be even higher,” Mr. Chatinover said. “It’s probably still an undercount, but I think that it’s closer to where we are. I felt happy with it.”

Beyond mere population statistics, the census data also showed that the Island, like the country, is becoming more diverse. The Island’s black population jumped 67 per cent, from 477 people in 2010 to 798 people in 2020, outpacing white population growth threefold.

Latino and American Indian population increases also outpaced white population growth, albeit by slightly smaller amounts.

But the Island demographic that saw the largest population increase was the multi-racial category — described by officials involved with the census as an imperfect catch-all that likely includes a portion of the Island’s Brazilian population that does not identify as white.

Multi-racial populations skyrocketed in every town except Aquinnah, growing by nearly 400 per cent, from 494 multi-racial residents in 2010 to 1,914 in 2020. Non-white residents made up 14 per cent of the Island in 2010. They now make up 22 per cent, driving overall population growth on the Vineyard.

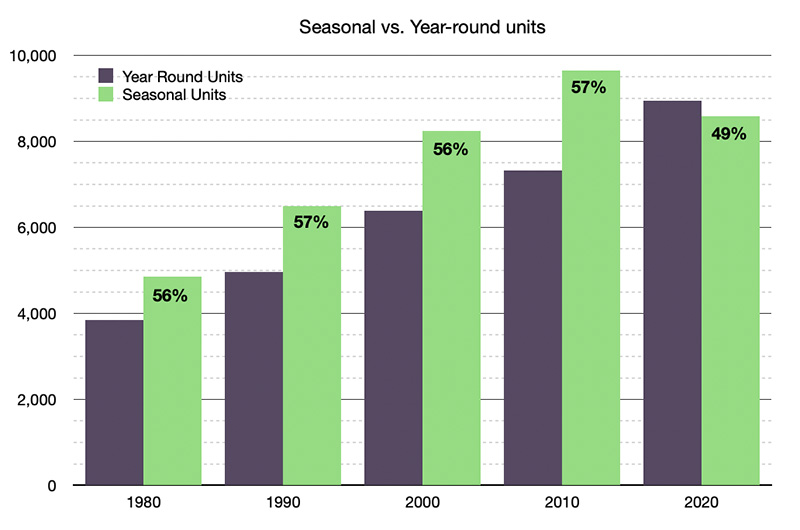

Yet even as population, and particularly, the non-white population, increased on the Island, growth in overall housing development slowed significantly over the past decade, census data showed, further squeezing a housing market that was upended by the pandemic.

The Island added 342 new housing units from 2010 to 2020, an increase of two per cent (from 17,188 to 17,530) while population went up by 10 times that. In the prior decade, the Island added 2,500 housing units, with much smaller population growth.

“This has a significant impact in terms of affordability, for those trying to get into the market and have sustainable year-round housing,” said commission housing and economic development planner Christine Flynn, who added she felt the 342 number was likely low. “And for Covid, the infusion of real estate values has only made that gap significantly wider.”

Just as housing development slows, year-round occupancy rates are rising rapidly, with more year-round than seasonal single-family residences on the Island for the first time in four decades (since data has been publicly available). Island homes are now 49 per cent seasonal, down approximately eight per cent from 2010, even though there has been little home development — suggesting population growth has also largely been driven by year-round residency. While the Island had 9,644 seasonal homes in 2010, it had about 8,580 in 2020, making it possible that as many as 1,000 homes shifted from seasonal to year-round residences — a shift planners believe was mainly borne out during the past year.

“There were second-home owners who opted to come to the Vineyard to stay for the pandemic, and a significant increase in those who opted to rent a home and work remotely,” Ms. Flynn said.

Mr. Turner and Ms. Flynn said the commission will continue to mine the more granular data in the hopes of better understanding the Vineyard’s changing demographic trends. While they were — at different points — surprised, heartened and concerned with the results, there was general excitement that the census bore out year-round population growth that had been felt anecdotally for the past 10 years.

They now have hard data to prove it.

“There was a lot of work that went into this. We hired a person to help do it, and we did it because we felt like we’ve seen all the incidentals,” Mr. Turner said. “Traffic counts are higher. There’s a lot of home sales. All the incidentals that you’re looking at have all been higher. So no, I’m not surprised at all by the population growth. But by the degree of it — I probably am.”

Comments (9)

Comments

Comment policy »