There is no purer pleasure for anglers on Martha’s Vineyard than the tug on the line of the first striped bass of the season. The fish needn’t be large, and likely isn’t. But that first hit in early May or June, that initial electric transfer of wild energy along the thinnest of filaments from migrating fish to hopeful human, renews a seasonal relationship that is as old as the Island itself. There are other fish in the sea, of course, but the return of stripers on their ancient journey up the Atlantic is a promise fulfilled. Stripers are the preeminent fish of summer; they carry the season with them.

But the seasons are changing in the waters that the striped bass inhabit. No one can say exactly how any single species will ultimately be affected by the ongoing global climate change. One thing is certain according to the scientists who study both fish and climate, however. The change is already underway at every point in the striped bass’s complicated life cycle.

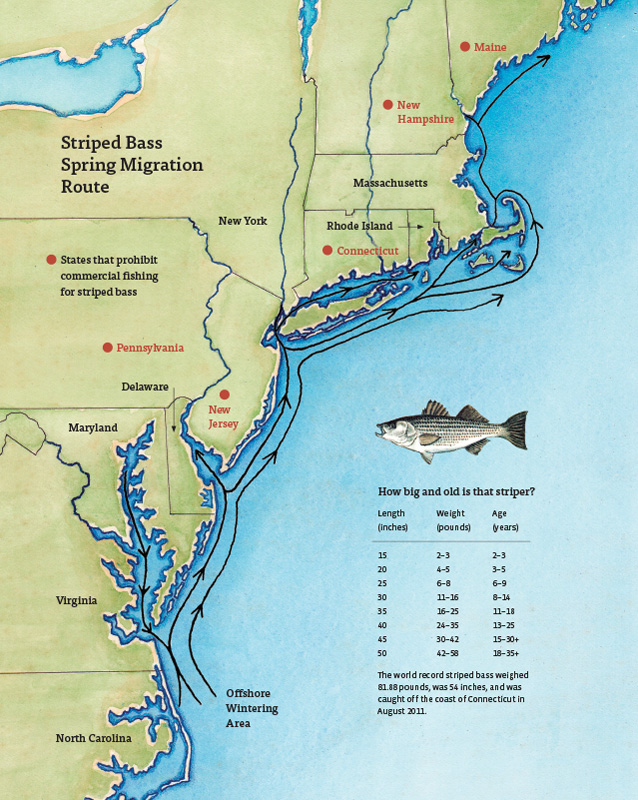

It’s changing in the Chesapeake, Hudson, Delaware and other estuaries where stripers spawn over the course of a few weeks in the spring, and where they live for the first few years of their lives. It’s changing up and down the coast, where the adult fish migrate north in summer following some combination of warmer water, baitfish concentrations, and an internal genetic compass. It’s changing in the waters of the continental shelf, where great schools of stripers hold in the winter months after the same genetic compass brings them back past the Vineyard in the fall. It’s even changing in the far northern waters of Canada, where pioneer striped bass may be colonizing new habitats at the expense of other species.

Global climate change is, as the name implies, a worldwide phenomenon. But it is not a uniform process. Numerous scientific studies have shown that warming in the northwest Atlantic has been accelerating since 2003, and the region is currently considered to be changing faster than 99 per cent of the rest of the world’s oceans.

“The reason the northwest Atlantic, and particularly the Gulf of Maine and Southern New England, is so susceptible to the warming is it’s a double whammy,” said Dr. Glen Gawarkiewicz via Zoom from his office at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, where he is associate scientist for the physical oceanography department. “You’ve got changes to the jet stream there. The biggest example was in 2012, when the jet stream never brought cold air south in winter. That was the warmest on record, though I bet 2021 beats it.”

There were immediate effects on some species. “You may remember that was the year the lobster fishery was disrupted,” Dr. Gawarkiewicz said. “There were the lobster wars with Canada, where Canada was refusing to process lobsters because the molting timing changed by six weeks. That was also when the puffin chicks were starving, because butterfish went into the Gulf of Maine and replaced a lot of the other species that could fit in the puffin chick’s gullets.”

Dr. Gawarkiewicz’s own research focuses not on atmospheric currents, but on the waters at the edge of the continental shelf, which begins some 80 miles south of the Vineyard. There, studies have conclusively shown that the Gulf Stream, the great oceanic current that brings warm water up the coast of North America into the North Atlantic, has become far less predictable over the past two decades.

“The double whammy is the Gulf Stream has much bigger meanders, so it’s bringing on periodically anywhere from five to twelve degree warmer water on top of what the jet stream is doing,” Dr. Gawarkiewicz explained. The meanders, called warm core rings, are like great temporary and unpredictable eddies that carry warmer, saltier water far closer to land than the main stem of the Gulf Stream normally flows.

The rings have always occurred, but the typical number of them that occur each year has grown from eighteen in the late 20th century, to thirty-two a year in the decades since 2000. Dr. Gawarkiewicz said that in recent years the rings have also been coming far closer to land and persisting longer before dissipating.

“In August of 2018 we had another one of those shocking ‘I don’t believe my instruments’ moments,” the scientist said. “We did a profile of temperature and salinity and there was salinity over thirty-six. We were just off of Nomans, and that’s undiluted Gulf Stream water.”

Nomans is an uninhabited island roughly five miles south of the Vineyard. “That’s an enormous difference in salinity so obviously you have an entirely different assemblage of organisms that thrive in that,” Dr. Gawarkeiwicz said.

The increase in salinity of the waters near and on the continental shelf was something of a surprise to researchers, who as recently as 2014 expected that the enormous inflow of fresh water melting out of Greenland and elsewhere would have the opposite effect.

“We are definitely getting pulses of fresh water with extreme rainfall events,” said Dr. Gawarkeiwicz. “But in general it’s the increasing influence of the Gulf Stream that has been more important than the ice melt coming down from the north.”

•

Striped bass, being diadromous, live part of their lives in fresh water and part of their lives in the ocean. As a result, they have a wide tolerance for changes in the chemistry of the water they inhabit. Except, that is, for the crucial first few weeks before they hatch. Females reach sexual maturity at between four and eight years old, males at around two to three years. Though their “natal fidelity” is likely not as high as salmon, adult stripers almost invariably return to the river of their birth in late winter or early spring. There, a 20-year-old, 40-plus-pound female can deposit as many as three million eggs, which are fertilized as they are released by groups of much smaller males.

The eggs are deposited in fresh or brackish water above the tide line over the course of a month or more. Fertilized eggs drift in the water column for up to about 80 hours before hatching. This period is when the striped bass as a species is probably most vulnerable to unusual weather, regardless of whether it’s caused by cyclical variation or by long-term climate change. If for some reason the fertilized eggs drift prematurely into the saltier ocean water, chances are good they won’t hatch at all.

“Striped bass do best with a cold, wet spring,” said Benjamin Gahagan, a diadromous fish biologist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. A large and steady flow of fresh cold water from upstream creates what he called “this big, thick boundary layer” between salt and fresh water with plenty of food for the larval fish.

“So cold and wet is good. Warm and dry is better for bluefish and menhaden and some other things,” said Mr. Gahagan, who is based in Gloucester. “And that’s the big question. Is climate change going to mess that dynamic up?”

Historically the most important spawning area for the fish that migrate past Martha’s Vineyard every summer is the Chesapeake Bay, followed by the Hudson River. In the Chesapeake in particular, Mr. Gahagan said, “environmental conditions for successful reproduction of large year classes have been pretty consistently poor since 2005, and maybe going back to 2000 if you really want to push it.”

One possible response to warmer springs may be an earlier spawning period. A 2014 study done by scientists at the University of Maryland showed that large female striped bass, which tend to spawn earlier than smaller females, migrated to their spawning grounds roughly three days earlier for every increase in water temperature of one degree Celsius.

One concern is that while some fish may successfully breed earlier in the year in response to warmer temperatures, the date at the end of the spawning period after which it is too warm for breeding may be shifting back even faster. Mr. Gahagan said the American river herring, which used to be plentiful enough on the Vineyard to support a major fishery but has declined markedly in the past century, may be a good analogy. “The spawning window for some river herring runs seems to be getting narrower over time,” Mr. Gahagan said.

Other research has shown that unusually strong storm events can potentially be the cause of unusual mortality levels for striped bass eggs and larvae. This suggests that the increased volatility of weather associated with climate change may also affect spawning success in the Chesapeake and elsewhere.

Even if striped bass eggs do successfully hatch, and the young of the year reach the age where they can tolerate saltier waters, there are other challenges in the Chesapeake before the fish mature enough to leave for the open ocean. Mr. Gahagan noted that there are now more than 17 million people living in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, and not all the issues are strictly related to climate change. There is ample evidence from studies of the Chesapeake and elsewhere, however, that warmer water temperatures can exacerbate water quality issues including hypoxia, or low oxygenation of the water.

“Most summers now, a great part of the center of the bay is a dead zone and it pushes all of the life to the edges,” Mr. Gahagan said. “It becomes a very habitat-limited place with these very narrow windows along the shoreline where there’s enough oxygen and the temperature is low enough for fish to be surviving and thriving. So we don’t really know what that’s doing to striped bass and a bunch of other fish, but it’s probably not good.”

“Is this a climate driven thing?” Mr. Gahagian asked rhetorically. “Is this a human driven thing? I’m someone who is very opposed to reductionism. I think both of those things have places in the conversation. But now we are at a point where it looks like that engine of the Chesapeake isn’t quite firing on all cylinders and hasn’t been for 20 years.”

•

The Chesapeake is by no means a lost cause, and it will remain the most important nursery for striped bass in the foreseeable future. Still, it’s comforting to striper fans that there are other estuaries where the fish reproduce with varying success. Mr. Gahagan is currently working with Nathalie M. LeBlanc, a biologist and computer scientist with the University of New Brunswick, and other colleagues to use cutting edge technologies, including genetic markers and acoustic telemetry to gain a better understanding of what is a far more complex network of striped bass migrations and spawning behaviors than previously thought.

“Over past 20 to 25 years the technology that has become available for scientists to track fish or ask fish questions about fishes early life histories and past has just kind of blossomed,” Mr. Gahagan said. “We have had no reliable way to break up the coastal stock, all these fish that are caught out in the ocean, or migrating between Maine and North Carolina over the course of the year. There’s been no way to say ‘oh these are from Hudson these are from Chesapeake Bay.’ So on and so on.”

The project is in the early stages, and will be the basis of a PhD that Mr. Gahagan is pursuing at the University of Massachusetts. There has not yet been enough research specific to striped bass to say anything definitive yet about whether climate change is causing striped bass to shift their spawning patterns geographically, Mr. Gahagan said. But based on his work with other species, and the work of others, he wouldn’t be surprised to see the evidence emerge.

“I think if you look across fish and even diagenous fish, other diagenous fish, there has been some research and there’s been a lot of anecdotal observations and research to show that there have been changes underway,” Mr. Gahagan said. “There are probably people on the Vineyard who remember fishing for rainbow smelt,” Mr. Gahagan said. Rainbow smelt are a small diadromous fish that spawn in cold estuarine environments. “In the early 1950s the southern extent of the range for rainbow smelt was the Chesapeake Bay. And southern extent of the range now is Massachusetts. They are disappearing now from Massachusetts and New Hampshire. And even Maine now is seeing decline. So it’s not just an urbanization or a coastal population issue.”

“I don’t know if we are seeing that for striped bass yet. I personally think we are going to start seeing that,” Mr. Gahagan said. “And a big factor there is just that there is no system that has the available breeding habitat that the Chesapeake has until you get up to the St. Lawrence. There’s nothing to rival it on the eastern seaboard until you get way further up into the Canadian Maritimes.”

Historically there were healthy breeding populations of striped bass in the St. Lawrence and in all the large rivers of Maine. But most of those populations were lost or seriously degraded in the 19th and 20th centuries, along with their genetic diversity. The primary cause was not climate change, but dams constructed near the head of the tide, which cut off or eliminated the spawning habitat. There has been some progress in restoring and restocking some of the rivers in recent decades, notably the Kennebec in Maine. In the St. Lawrence, a breeding population has been reestablished with stocked fish from further south.

“For me, thinking on a century time scale, I think if you want to be serious about having as many striped bass for our great grandkids as we have — if we manage to not screw everything else up — we need to think of undamming some of these big rivers in Maine and wherever else we can that might be able to host striped bass, and restoring the habitat so they can spawn there,” Mr. Gahagan said.

“But it’s going to be a kind of hopscotch course to get the fish up to a point where the St Lawrence is in the thermal sweet spot for that fish and is really just pumping out tons of fish. And then Massachusetts is going to be at the southern end of the range rather than the northern end.”

•

Striped bass are not in danger of extinction. There are stripers far south of the Chesapeake in the St. John River in Florida, and in the Appalachicola system in the Gulf of Mexico. There are stripers in the Pacific, where they were intentionally introduced in San Francisco a century and a half ago and now range from Mexico to British Columbia.

Nor are they complete strangers to climate change. When the most recent ice age began to wane some 12,000 years ago, there were no stripers north of the glacial moraines that would become Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, and Cape Cod. Even the Chesapeake and the mid-Atlantic may have then been too cold for them. Twice in the past five years, however, huge schools of small stripers have made fall runs up the Labrador coast in the far north, where they have stayed too long and been killed, presumably by the cold. What they were feeding on is not certain, but likely includes Atlantic salmon smolt.

“They are super resilient fish,” said Mr. Gahagan. “They do crazy things. They hold over in deep holes in fresh water systems for the winter. They get in that cold water and their metabolism slows down so they don’t have to burn a lot of energy. At the same time they make ridiculous coastal migrations of thousands of miles annually.”

“They’ll survive,” he said. “It’s just a question of are they going to be this cornerstone of our cultural and recreational experience on the East Coast. That’s going to be the question.”

Comments (15)

Comments

Comment policy »