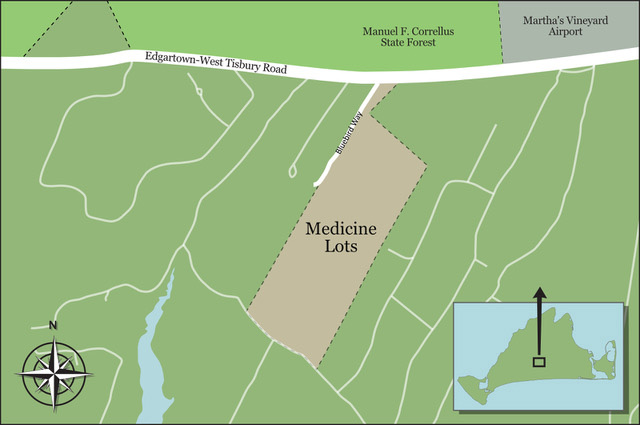

Along the Edgartown-West Tisbury Road just past Bluebird Way near the airport there is an extra chill in the air, the cause of which dates back to the ice age. The area is home to one of the Island’s last undeveloped frost bottoms, an extremely rare micro-habitat made up of remnants from glacial riverbeds.

This particular 97-acre frost bottom is surrounded by sandplain coastal barrens, a habitat that’s home to 19 plant and animal species listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

But in recent weeks, the distant roar of excavators can also be heard, as conservationists from The Nature Conservancy look to save the land by tearing some of it up. The area, known as the Medicine Lots, has become overgrown and as a result is at risk of losing some of its key species.

The restoration effort has been in the planning stages for years and is expected to be finished in early March, said Mike Whittemore, the Nature Conservancy stewardship manager for the Cape and Islands.

“I know it looks a little bit like a wasteland right now,” Mr. Whittemore said during a recent visit to the site. “After this initial project we won’t be doing something this extreme again. We’ll just subtly manage it, keeping an eye on the structure and vegetation so that species can benefit.”

To maintain the Medicine Lots’ biodiversity, human intervention is critical, Mr. Whittemore continued. Humans are also ultimately responsible for the ecosystem’s fragility, he added.

Throughout millennia the barrens have relied on wildfires to help nourish the soil and keep shrubbery at bay. But decades of fire prevention have transformed the area from an open grassy area to a thick forest, leaving it in a state that’s unsuitable for many of its inhabitants and vulnerable to more intense and potentially devastating fires.

“[The conservancy] actually does a fair amount of controlled burning on the Island,” said Mr. Whittemore. “We’ll actually be burning three other sites this year . . . I wanted to get this site approved but there’s a lot of very expensive housing in the area and it’s a liability.”

The best time to conduct controlled burns is in the summer and fall when the ground is at its driest and plants are starting to seed, added Mr. Whittemore. But this also happens to be peak tourist season.

Instead of controlled burns, Mr. Whittemore and his team are focusing on removing and mowing overgrowth, and clearing out most of the oak trees with the exception of some scrub oak, a tree that is beneficial to a rare and critical species of moth.

The goal, he explained, is to create a mosaic of flora in the sandplain barrens that prioritizes the health and biodiversity of the frost bottom.

Restoration of the Medicine Lots has been a long time coming. The land was originally acquired by the Nature Conservancy in 2013 with the help of then director of conservation strategies Tom Chase, who had his eye on the property for decades.

Mr. Chase’s family roots go back generations on the Island, and he originally wanted to purchase the land in 1986 while working with the Trustees of the Reservations, but the deal fell through due to title issues. He finally secured the property for the Nature Conservancy nearly 27 years later with the help of attorney Anne Risso and land protection specialist David McGowan. Mr. Chase, though no longer affiliated with the Nature Conservancy, remains passionate about Island conservation and is pleased to see the project finally take place.

“It’s so gratifying to see when a conservation project is pursued to actual ecological restoration,” he said. “Many of these things take incredible hours of human endeavor and generations of time.”

Mr. Chase is the founder and CEO of the nonprofit Village and Wilderness, which focuses on local climate change adaptation and mitigation. He said he feels that the community’s understanding of the importance of environmental protection has weakened, and in the era of climate change, many of the Vineyard’s plant and animal species are at risk.

“I am saddened to say that much of the Vineyard population has forgotten the truth that used to be so well known to all of us,” he said.

Most frost bottom species the Nature Conservancy is working to protect are indicator species, he explained. Their presence is a sign that a habitat is healthy. They help with pollination, carbon sequestration and watershed protection.

“We can’t necessarily see pollination occur, other than maybe a single bee pollinating a tomato plant,” said Mr. Chase. “It’s hard for people to understand that most of the benefits they get from nature isn’t the stuff that they can see in their hand.”

Mr. Chase stressed that public education is just as important as the physical restoration work that’s being done. Sometimes the critical role that biodiversity plays isn’t easily understood, but the best way to learn, he said, is by taking a walk on the land with someone who’s been there longer.

“Conservation work, unlike what many people understand, takes decades and multiple generations to secure,” he said. “In the meantime, walk the land.”

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »