Seventy five miles off the coast of the Vineyard, where cool shallow waters drop off into a salty abyss, robotic submarines swam for years between long buoy lines straddling sea and sky. This metallic forest of oceanographic equipment, the Pioneer Array, has dutifully collected advanced environmental data since 2016.

But as of this September that forest was uprooted, and as of Wednesday it was replanted off the coast of North Carolina

The relocation of the Pioneer Array signals the end of an era for the high-tech system, one of five active stations in the National Science Foundation’s Ocean Observatories Initiative. Over the past six years, it has captured a wealth of data on changing conditions off the Vineyard coast, informing nearly a decade of groundbreaking research into rapidly shifting ocean currents with implications for local fisheries and global climate change trends.

“Researchers have some very interesting results from the New England array,” said Al Plueddemann, a physical oceanography scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), who worked on developing the array.

It is an innovative project, probing the mysteries of waters much deeper than those another WHOI installation, the research buoy visible from South Beach.

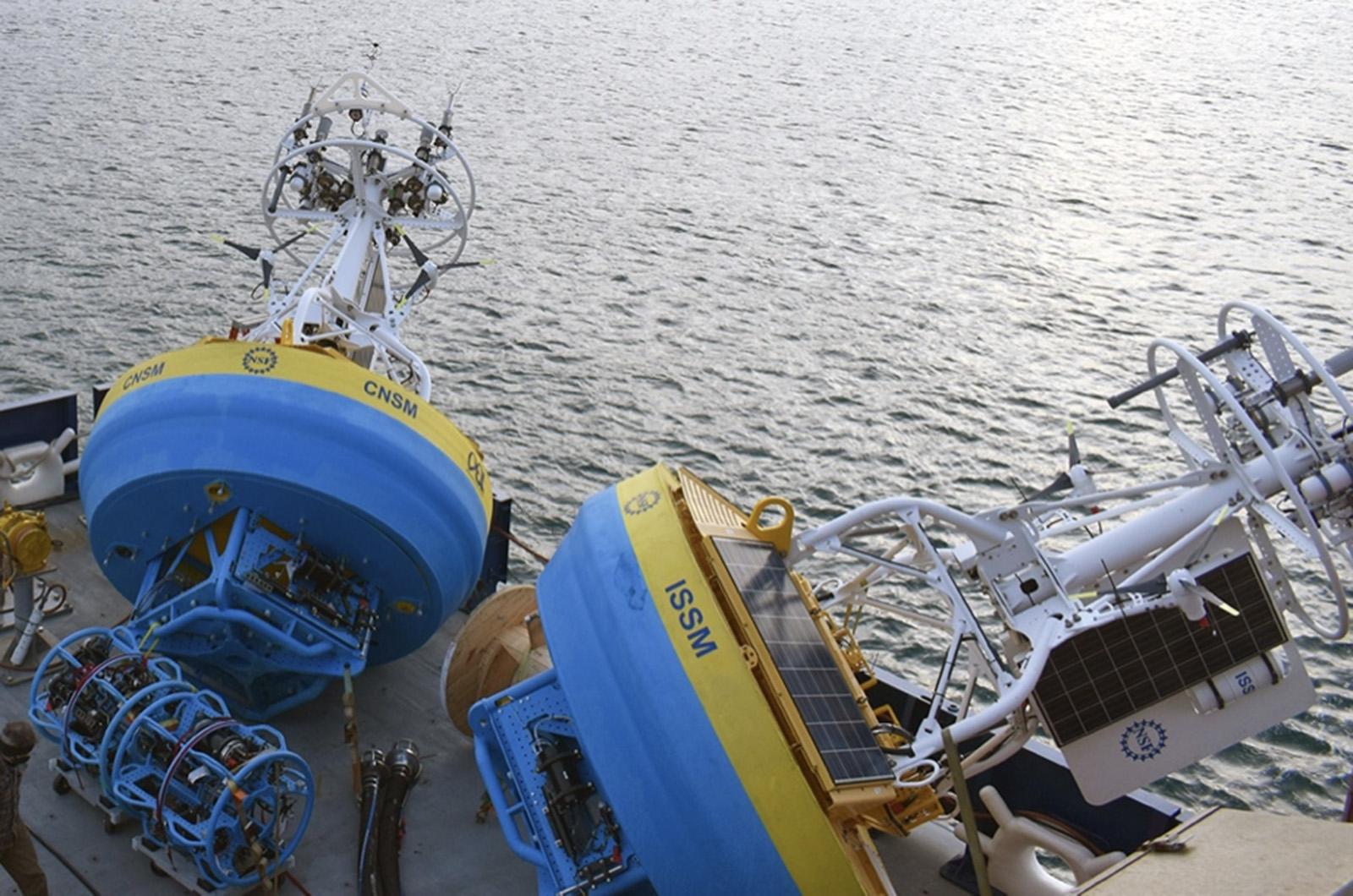

In an email to the Gazette sent from the deck of the RV Neil Armstrong in Charleston, S.C., Mr. Plueddemann described the technology involved in the Pioneer Array.

“The array is comprised of instrumented moorings, ocean gliders and propeller-driven [autonomous underwater vehicles],” he wrote, with each machine contributing its own strengths.

While slow roving gliders sample wide swaths of ocean, intermittent buoys send consistent data from a single point stretching from the surface to the ocean floor.

“The combination is more powerful than any one element,” Mr. Plueddemann wrote.

Just as important as the technology in the array was the location of its installation, the continental shelf break, where the shallow floor of the continental shelf, nearer the coast, dips down to the continental slope.

There, the group of subaqueous robotic systems and buoys became eager assistants to scientists studying a complex confluence of currents that occur in this area of maritime transition, as WHOI research associate Svenja Ryan explained.

“The shelf region has experienced this drastic change and warming since 2010 . . . and we’re trying to understand the physical mechanisms that potentially drive these changes,” said Ms. Ryan.

It is an area of transition, she said, home to the shelf break front phenomenon, where cooler and fresher waters, ultimately coming from the Arctic, collide with a warm salty current from the Gulf Stream. Interactions between those waters drive local conditions, both physical and biological, but in recent decades the front has ceased to behave as it normally would.

“It’s a new system that we have to understand,” said Ms. Ryan.

As researchers have begun to untangle the web of factors contributing to the “marine heat wave” events now sweeping the seas of the northeast, the Pioneer Array has been indispensable for gathering data.

“We really don’t have a lot of underwater observations,” said Ms. Ryan of the data collection landscape.

The array’s contributing mountains of data about water temperature, salinity and atmospheric conditions, all on a 24/7 basis, has allowed them to start cracking the code of maritime warmth. Though many questions remain unanswered, researchers have found the phenomenon of “warm core rings” to be a major driving factor in the region. These rings, huge oceanic donuts of warm water, originate as swirling eddies thrown off the Gulf Stream.

Research from WHOI scientist Magdalena Andres has indicated that the Gulf Stream is becoming “wigglier,” said Ms. Ryan, and is thus throwing off more of these rings.

Such abstract phenomena have a real, material impact on New England fishermen. Ms. Ryan said researchers have also tapped into the unrivaled environmental awareness of local fishermen.

“My advisor, Glen Gawarkiewicz, has established an incredible relationship with the local fishing industry over recent years, and the Pioneer Array was a key part of that,” she said.

Fishermen have noted a marked increase in warm-water fish, and especially squid, on the continental shelf. Combining fishermen’s observations with Pioneer data, researchers have developed a working theory that the warm core rings act like a warm-water bridge between the gulf stream and the continental shelf, enabling unusual aquatic migrations.

But much work remains in order to understand ocean dynamics, especially as climate change becomes more of a factor.

Mr. Plueddemann said the new location for the Pioneer Array, a region known as the Mid-Atlantic Bight, will help provide more unique data to study.

“[The bight] is an important region of the U.S. coastal ocean and has a vibrant ecosystem associated with complex physical processes. Arguably more complex than the New England site,” he said. “Re-locating the array makes sense, and will likely have a big payoff in terms of new understanding.”

Meanwhile, back in Woods Hole, Ms. Ryan said the huge body of data collected during the Pioneer’s Vineyard years remains a rich area of research, and one with continuing relevance for local mariners.

“It’s a very exciting region, particularly because it has these strong implications on the local fishery and the community. To me that’s a strong motivation to work in this region...At least for me personally, it’s about making these connections.”

Comments

Comment policy »