Looming above a serene village in the Northeast of France, against the luminous navy sky at dawn or dusk, two objects float, flanking a crescent moon: a massive boulder and its mirror image as a cloud.

The images are part of René Magritte’s painting, The Battle of the Argonne, and for Aquinnah summer resident, pre-historian and independent researcher Duncan Caldwell, they are secrets to unravel.

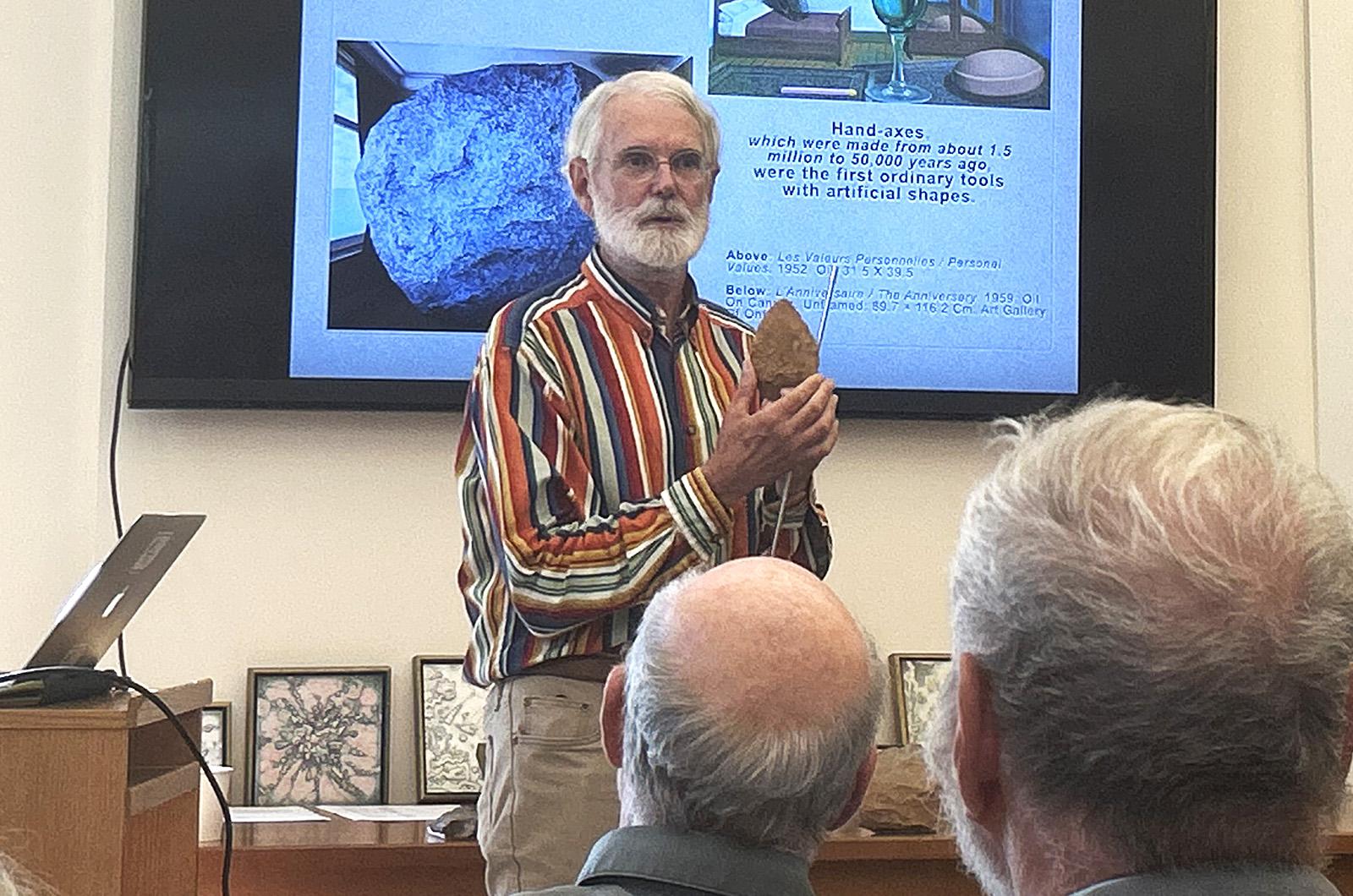

Mr. Caldwell gave a talk at the Chilmark Library last week, connecting Mr. Magritte’s work to the artistry of a much earlier era. The boulder in the Battle of Argonne, he said, as well as those in dozens of other of Magritte's well known boulder paintings, are in fact accurate portrayals of prehistoric hand axe tools.

“They could be illustrations from a prehistoric tool guide,” Mr. Caldwell said, while discussing his forthcoming article, The Prehistoric Secret of Magritte’s Boulders: The Hand-axe Paintings, to be published in the journal RES: Anthropology & Aesthetics in conjunction with the Chicago University Press and Harvard’s Peabody Museum.

Mr. Caldwell has had a lifelong connection to the Vineyard, briefly attending the Chilmark School during a globetrotting childhood that stretched from Chilmark to Vietnam, Syria and Cyprus. Since the 1970s, Mr. Caldwell has split his time between Paris and Aquinnah.

During his decades-long career, Mr. Caldwell has written broadly on topics of art and anthropology. His most recent paper is his third to be published by the Peabody Museum, having previously written papers for them on the topics of African American and Congolese segregated troops during WWI and on an interpretation of artifacts pre-contact “woodland” culture of Native Americans east of the Mississippi.

His deep dive into Magritte paintings draws from a wide range of interests, from art and technology of the ancient past, to the artistic movements of the 20th century.

“This has been my mind for a very, very long time,” he told the audience. “I was surprised that people hadn’t recognized that Magritte’s boulders . . . are typologically accurate depictions of hand axes.”

Mr. Caldwell, both a student and a collector of prehistoric hand axes, also called bifaces, was just the man to discover such a connection.

“I’ve written five different tool guides about prehistoric tools of the old world,” he said.

He also brought to the event some of his collection of hand axes for display. He presented one such specimen, a biface from the central Sahara, as evidence for his theory, pointing out the “conchoidal fractures” typical to the tools.

“These flake scars don’t occur naturally,” he said, but they do appear in the painting of Mr. Magritte.

But the identification of the boulders as depictions of ancient tools raises the question of interpretation, a difficult task when considering an artist like Mr. Magritte who never discussed the meaning of his works.

“He was a deadpan trickster, and even a malevolent one,” said Mr. Caldwell of the artist’s sensibility. He recounted a story of how, as a boy in Belgium, Mr. Magritte and his brothers purposely starved the family donkey. That behavior, he said, extended to Mr. Magritte's art.

“Magritte set up to jolt the audience out of complacency, to provoke in them feelings of discomfort,” he said.

In creating the hand axe, Mr. Caldwell said, the “first artist” created a tool, a weapon and a piece of non-representational art.

“Magritte seems to be saying that the implications of man’s first breakthrough now haunt our entire existence,” Mr. Caldwell said. “[Magritte’s boulders] still bear witness to the strangeness of our universe, and that feeling that is mysterious, not necessarily in a sentimental way.”

Comments

Comment policy »