In the autumn of 1825, three young women, Chilmarkers all, departed from their small, insular, up-Island community. The three of them, Lovey Mayhew, the eldest at 24, along with sisters Sally and Mary Smith, ages 19 and 14, boarded a boat for a long journey to inland Connecticut.

The girls could not speak, nor could they hear. They knew just one language: Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language. The journey would make them the first residents of the Vineyard to attend the new American School for the Deaf, located in Hartford, Conn.

“Imagine you’re a parent in 1825, and you’re allowing your daughters to ship off to New Haven and then find their way up to Hartford....This required some courage,” said Richard Meier, a professor of linguistics at the University of Texas at Austin.

“We’ve found one story in which a deaf woman lobbied, pleaded with her father for seven years, apparently, to be allowed to go,” he said. “The rate of literacy might have been higher in the deaf population on Martha’s Vineyard than it was in the general population.”

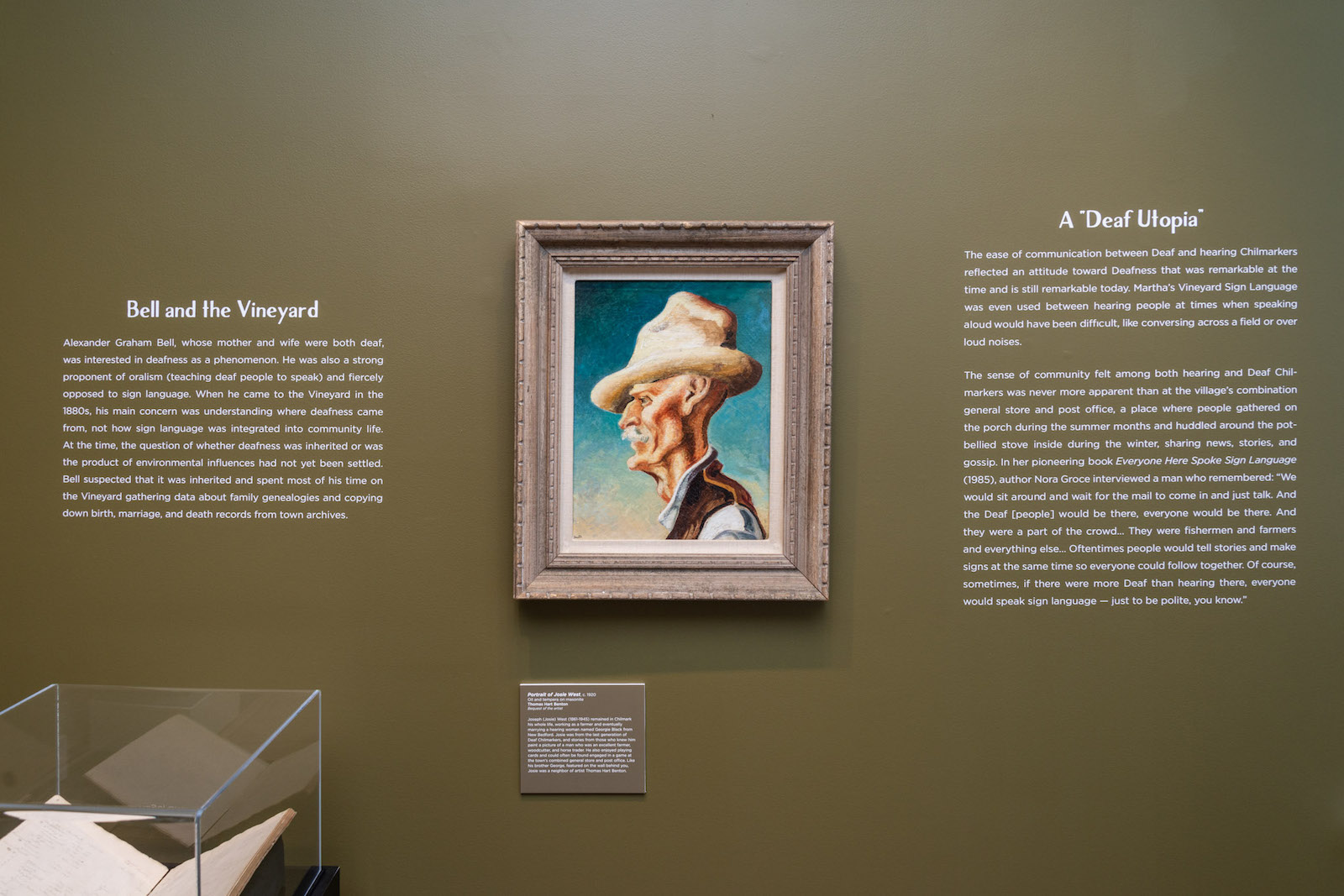

For nearly four decades, ever since anthropologist Nora Ellen Groce published Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language, her landmark study of Martha’s Vineyard sign language, the Island has remained a touchstone for researchers studying the emergence and function of “village” sign language in local societies. Less studied, however, is the relationship the Vineyard had to the mainland deaf community of the early-19th century and the impact those connections had back home.

That topic, and its implications for the traditional account of the Island’s deaf community, is the topic of a new paper entitled The Historical Demography of the Martha’s Vineyard Signing Community, authored by Mr. Meier and fellow University of Texas at Austin linguistics professor Justin Power. The paper was recently published in the Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education.

“The perspective that we tried to take on the story was trying to emphasize the agency of the deaf people who lived on Martha’s Vineyard,” said Mr. Power. “We tried to frame it to focus not on what happened to the deaf population necessarily, but that those deaf individuals chose to become members of a wider deaf community.”

Ms. Groce’s book Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language is still a central example for researchers studying the emergence of sign languages, Mr. Meir said, and was their starting point for research.

“It was really one of the first detailed histories of a so-called village sign language and for that reason it’s extremely important,” he said. “For the last 20 or more years, I’ve taught Nora Ellen Groce’s book in graduate and undergraduate classes.”

The phenomenon of village sign languages, which develop organically in isolated deaf communities, are in turn important examples for the broader field of linguistics.

“If we look at spoken languages, we can’t examine in front of our eyes the development of a new language. There’s always a prior form of a spoken language,” Mr. Meier explained. “On the other hand, we can find deaf communities where there is not a continuous history of sign language being passed down.”

And so, when the pair of researchers set out to reexamine Ms. Groce’s study, her account of the language’s origins were key.

For Ms. Groce, the story began not on the Vineyard, but in the rural county of Kent in England, where she theorized hereditary deafness could have caused a local sign language to emerge in the early-17th century. Ms. Groce found evidence for that theory in an account of a prominent diplomat from that time period, George Downing, namesake of Downing street in London, who grew up in Kent.

“He apparently had a network of spies in London, and at least some of them were deaf,” Mr. Power said. “There’s the inference that because [George Downing] was able to sign with these deaf individuals, and he was from apparently from Kent, that maybe there was a widespread sign language.”

Ms. Groce then traced a small group of Kentish villagers on their journey as Puritan colonists to mainland Massachusetts, then to Martha’s Vineyard, theorizing that their sign language may have made the journey with them — a hypothesis that Mr. Power and Mr. Meir don’t agree with.

“We have very thin evidence of any such community,” Mr. Power said.

Instead, in their analysis of census records, correspondence and other historical documents, Mr. Power and Mr. Meier contend that Vineyard sign language did not emerge until the late-18th century.

“We’re arguing that the language probably really dates to 1785. And that’s when deafness starts to become frequent in Chilmark,” Mr. Power said.

The researchers found evidence of only a few scattered deaf individuals on the Island beforehand. By 1785, however, there were 11 deaf individuals, all concentrated around Squibnocket.

“With 11 deaf individuals plus their family members in a relatively-small town, you can certainly imagine that a sign language had developed,” he said.

This analysis, Mr. Meier said, re-centers the role of the Vineyard.

“We’re suggesting that Martha’s Vineyard sign language was a creation of the community on the Island. It was not imported from England.”

The idea of a later emergence of Vineyard sign language was borne out by recent research from University of Texas at Austin PhD candidate Lee Orfila, who compared records of Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language with other contemporary English sign languages. Her paper is now undergoing peer review.

“As for the comparison with British Sign Language, the results are pretty messy. It wasn’t a clear picture,” she said, noting she was unable to draw any clear connection between the two.

What Ms. Orfila did find, however, was a clear connection between the Vineyard’s sign language and American sign language, which emerged in the early- 19th century. That connection matches with another one of Mr. Power’s and Mr. Meier’s key findings: beginning in 1825, as more deaf Islanders attended mainland schools, the Island deaf community ceased to be isolated.

“Although prior scholarship has cast the Martha’s Vineyard signing community as a remote, outlying community,” they wrote in the paper’s introduction, “we will argue that, by the mid-19th century, it was well connected to the nascent New England signing community and that its growth and subsequent decline were in part caused by that connection.”

When deaf students returned to the Vineyard, they brought back strong linguistic influences from mainland sign language, though much Vineyard vocabulary — especially that relating to boats and fishing — remained unique.

Many students also returned with spouses, which the authors say may have led to the decline of deafness on the Island. As deaf Vineyarders had children with mainlanders who were deaf by different causes, the original genetic source of Island deafness faded away.

By the early 1950s, the last inheritor of Vineyard hereditary deafness died.

But for Mr. Power, the dwindling of the Vineyard deaf community is not merely a story of cultural loss, as it is sometimes made out to be.

“There’s one way to kind of frame this story as, there was this deaf and hearing utopia, where deaf and hearing individuals interacted perfectly in peace and in harmony. And then there was this event that disrupted that deaf Eden. And it sounds like a kind of tragedy,” he said. “But [deaf Islanders] were active participants in a new deaf community that was forming on the mainland. They chose to do that. And that, I think, gives the deaf people a little bit more agency and makes the story less of a tragedy.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »