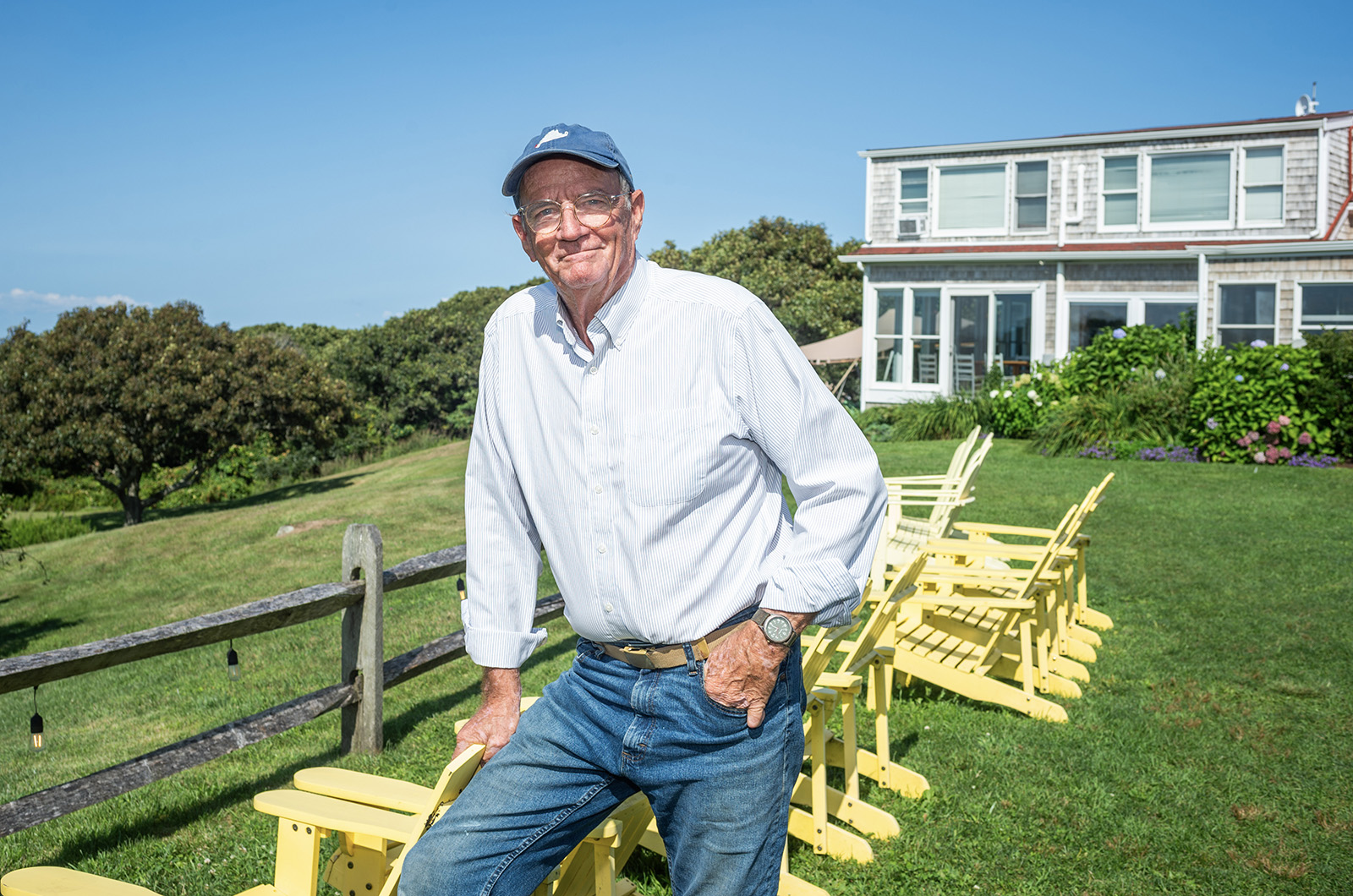

It has been years since a guest stayed at the Outermost Inn in Aquinnah.

The restaurant still bustles with activity, booking out weeks in advance. But since 2021, Hugh Taylor, the proprietor of the Outermost Inn, has put the inn’s eight guest rooms to an unconventional purpose: employee housing.

“I can’t say that it’s a permanent condition, but it certainly seems to work at this point,” Mr. Taylor said.

For Mr. Taylor and countless other Island businesses, providing employee housing has become a cost of doing business. With housing prices, both year-round and seasonal, continuing to rise to unprecedented levels, business owners must provide stable, subsidized housing for their workers, or risk losing them.

Larkin Stallings, owner and operator of the Ritz in Oak Bluffs, said he has no other option if he wants to stay in business.

“I don’t want to be a landlord. It’s not what I do for a living,” he said.

Mr. Stallings rents an apartment above the Ritz and leases another property on Edgartown-Vineyard Haven Road and offers the rooms to employees at a subsidized rate. And yet the two properties hardly make a dent in his housing needs, he said.

It is an Islandwide issue, one faced by both small and large businesses, who in addition to the demands of finding staff for the intense summer season when the bulk of their annual income is generated, must now come up with a patchwork of living arrangements. However, each added responsibility can bring with it new complications.

Martha’s Vineyard Commission housing planner Laura Silber said that when more than 20 Island business owners and nonprofit leaders met with the state secretary of housing earlier this summer, each said that employee housing “was not an ideal solution.”

“Every single business owner, nonprofit directors, small businesses, larger businesses, banking, all said they do not want to be having to provide housing for their employees,” Ms. Silber said.

They described employee housing as “a default position that they have to take responsibility for in order to keep their services running,” Ms. Silber said.

For employers, providing employee housing poses two main challenges. The Island’s housing supply is limited and expensive, so finding properties that employers can afford to lease or purchase can be difficult. And once housing is secured, employers face a host of ethical, legal and emotional issues not previously in their job description.

At Morning Glory Farm, Simon Athearn has overseen a continual push to expand employee housing.

In 2018, Morning Glory Farm built a small dormitory capable of housing nine workers, created to complement two cabins and an existing dormitory on the farm grounds. Over the past few months, Mr. Athearn has built five additional double-occupancy cabins on his family’s land in West Tisbury.

Mr. Athearn said that 38 workers — more than a quarter of the farm’s summer payroll — live in employee housing. More than half of those workers are now year-round staff members, a major shift after the pandemic drove up housing prices and rentals way past what employees could afford — even in the offseason.

“A big change for us was when what were stable Island employees lost their stable housing, and needed to move in with us in order to keep them on,” Mr. Athearn said.

The new cabins in West Tisbury were built to accommodate those year-round staffing needs, Mr. Athearn said.

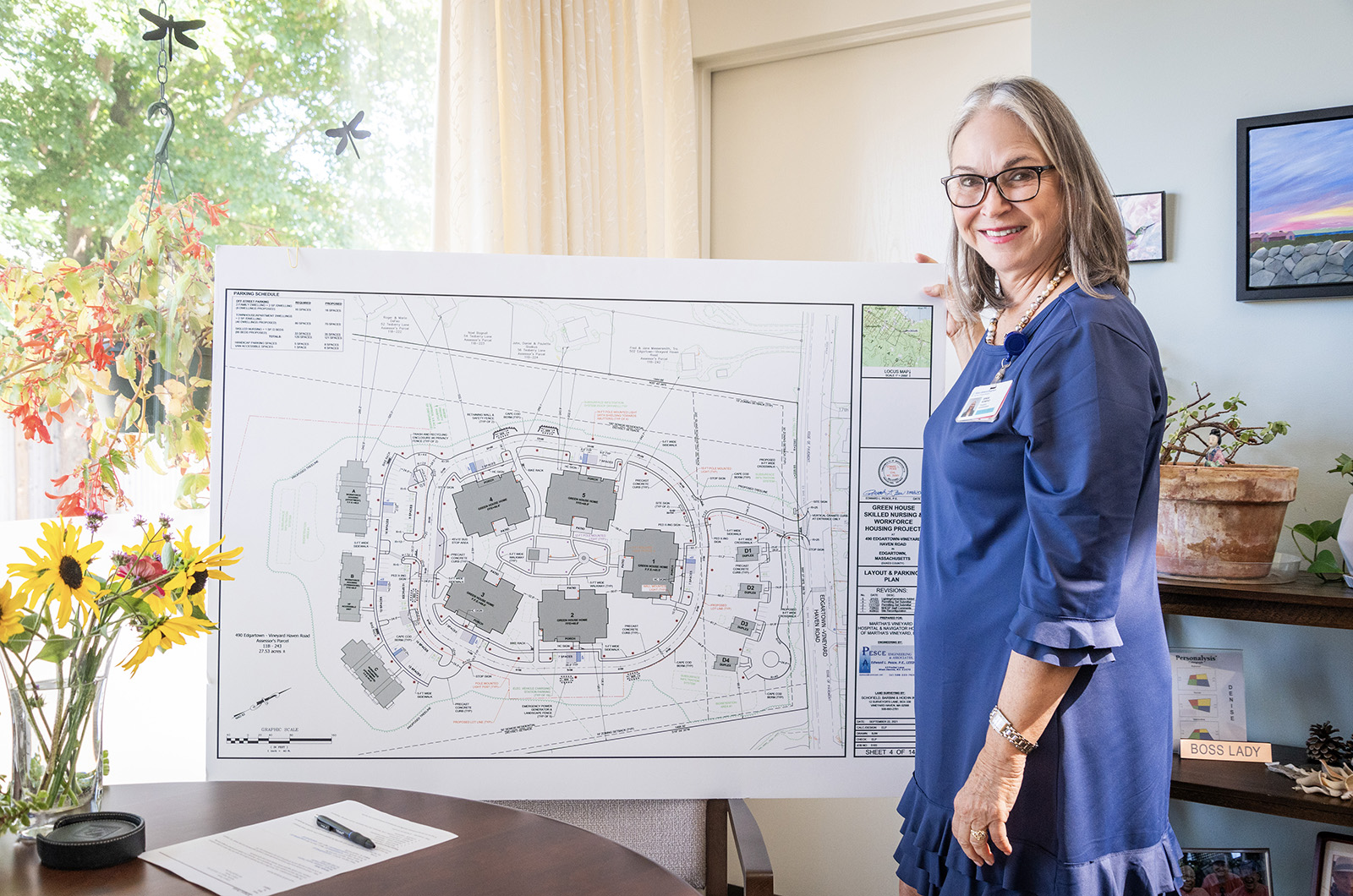

The scale of employee housing needs and costs increases by an order of magnitude with the size of an organization. Martha’s Vineyard Hospital president Denise Schepici said that 250 of the hospital’s 900 employees live in housing owned or leased by the hospital, which it provides to workers at a subsidized rate.

The number of employees housed by the hospital was up 48 per cent between July of this year and July of last year, Ms. Schepici said.

“We have everything from physicians who cover weekends and nights or are here for the summer, to nurses, all the way to water and facilities people, environmental services staff [in employee housing],” Ms. Schepici said.

The hospital currently holds 135 leases with 81 different landlords, Ms. Schepici said. Nearly all of those leases are for one year terms and therefore subject to unpredictable increases in rent. So, like Morning Glory, the hospital has begun a series of new employee housing construction projects, designed to scale down the number of leases it holds.

Navigator Homes, the planned long-term skilled nursing homes development set to replace Windemere next summer, includes 48 units of employee housing with 76 beds, to be divided between the nursing home (30 beds) and the hospital (46 beds). The employee housing alone will cost the hospital nearly $35 million, Ms. Schepici estimated.

A neighboring home owned by the hospital is also being renovated, Ms. Schepici said.

“My goal is to have controllable, affordable housing for hospital staff because if I don’t have hospital staff, we’re not going to have health care,” Ms. Schepici said.

As a result, Ms. Schepici must oversee an entire staff dedicated to managing the hospital’s employee housing. The hospital even employs a handyman, per diem, to service the failing refrigerators, broken screens and leaking air conditioners at leased units.

At the Harbor View Hotel, chief operating officer Alton Chun said that house-cleaners and facility staff double as the maintenance crew for the hotel’s employee housing, which, like the hospital, it owns and leases around the Island.

“If there’s maintenance, we have an engineering team. If there’s housekeeping, we have a housekeeping team here. So we do cross utilize some of our employees, which is also great because we want to take care of our employees like we would our guests,” Mr. Chun said.

With so many employees living in staff housing, Mr. Athearn and other employers said they have had to set up boundaries to mediate disputes.

At Morning Glory Farm, a live-in house manager at the dormitory reports regularly to the farm’s management on any facilities issues or personal misconduct. If repeated warnings are not heeded, employees can lose their housing, Mr. Athearn said.

Similar rules prevail at the hospital, Ms. Schepici said.

The close connection between employment and housing risks putting employers in difficult ethical, and even legal, positions: Can I let an employee go if they will lose their housing? Can I afford to kick someone out of housing if I will lose their labor?

“I’ve talked with several other Island businesses about this exact thing,” Mr. Athearn said.

Mr. Athearn said that his family are farmers and did not intend to be in the housing business, right down to providing amenities such as laundry soap and towels to workers in employee housing. And yet wading into the world of real estate is now a necessity.

“It would bristle for my dad to hear that,” Mr. Athearn said.

There is no going backwards, however, as the need for employee housing increases. Employers are making do in whatever ways they can, and they are looking to government officials to step up, both with funding and, when necessary, zoning changes.

The hospital’s Navigator Homes employee housing development required the amendment of town zoning laws, Ms. Schepici said. But for others, more granular issues exist.

Mr. Taylor said that he would happily build a multi-room summertime employee housing on the Outermost Inn’s nine acres. However, any new building would push the property passed its formal wastewater limit, he said.

Mr. Stallings said he hopes that members of the Island business and nonprofit communities can band together to create a permanent workforce housing development that could support summer workers and take the pressure off employers as landlords. That type of development is in the works in Provincetown, Nantucket and Rocky Mountain ski towns.

Ms. Silber also pointed to the need for a more proactive approach by the community and local government.

“We have a choice about how we want to handle this,” Ms. Silber said. “But it doesn’t happen automatically, it’s an intensive, long-term effort that takes professional coordination . . . and planning over the long term on the part of local governments. And it takes public funds to address.”

Comments (28)

Comments

Comment policy »