When Joe Solmonese, a longtime political strategist and year-round Island resident, was hired as CEO of the 2020 Democratic National Convention in Milwaukee a little over a year ago, he knew that there were going to have to be some changes.

He just didn’t know he was going to be making them from Chilmark.

“I came back to Chilmark on March 16,” Mr. Solmonese said in an interview with the Gazette this week. “And the first thing we did was reschedule. Now, it just seems like such a naive notion, to say ‘oh, we’ll just push it back five weeks.’ But at the time we thought we’d maybe solved the problem. Of course, we didn’t.”

“By the end of that week,” he recalled, “I knew that we would have to be prepared to think very differently about this.”

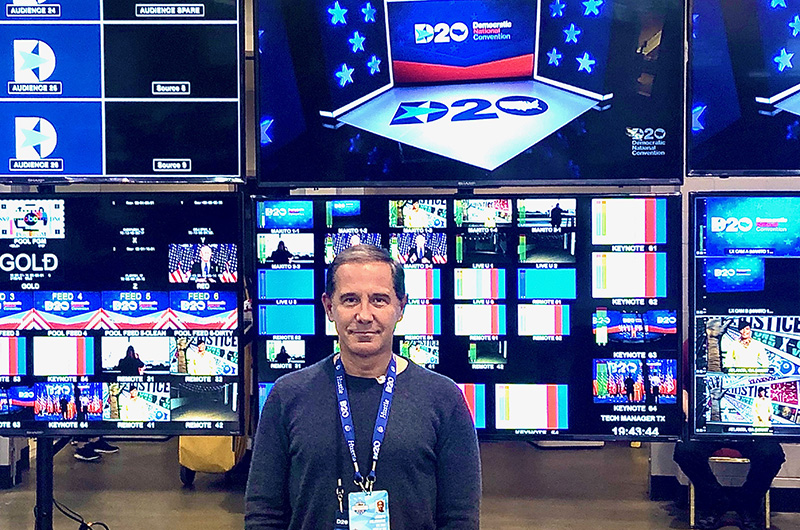

Over the course of the next six months, Mr. Solmonese led the effort to completely overhaul last week’s unprecedented 2020 Democratic convention, transforming it from a traditionally raucous, in-person affair into an intimate, but entirely virtual production — all from his house in the hills of Chilmark.

The timeworn traditions of live audiences, packed arenas and hotels, interminable political soliloquies, button collecting and delegate meet-and-greets were done away with, replaced with testimonials from regular Americans, fireside chats, a live-streamed roll call and an extremely strict five-minute time limit on Bill Clinton’s speaking slot.

A force majeure known as Covid-19 had made those changes necessary. But for Mr. Solmonese, who has been to every Democratic nomination convention since 1988, they were changes he had been, to some extent, planning all along — the natural evolution of an ancient, but now antiquated political tradition that had over time become more spectacle than substance.

It was the extent — and the immediacy of those changes — that he didn’t expect.

“We were thinking already about being more concise. We were already talking about having a more strategic narrative arc. We were already talking about the idea of having real people tell their stories,” Mr. Solmonese said. “A lot of that was already under way. But when Covid hit, what became apparent over April, May and June, was the degree to which we were going to have to do it virtually.”

Mr. Solmonese was hired to be CEO of the convention approximately one year ago. Although he had a long career in politics, working as a staffer in the Dukakis administration and as head of both EMILY’s List, a pro-choice political action committee, and the Human Rights Campaign, he had never run logistics and programming for an event as large, and as consequential, as the DNC.

He quickly got an apartment in Milwaukee and began commuting between Chilmark, where he has lived for the past two years with his husband Jed Hastings and their dog Owen, and Wisconsin. The first six months were relatively normal, focusing on event logistics while preparing for the usual shifts and unpredictability that come with political work in an election year.

“We were just in the initial planning phases. How many hotel rooms do we need to rent? How many buses do we need to rent? What does the security footprint look like?” Mr. Solmonese said. “That’s a lot of what the early convention planning is, the operational part of it, and the raising of the money. Then you kind of have to wait and see.”

He didn’t have to wait long. By Super Tuesday, the once-crowded political field had played itself out — in incredibly fast and conclusive fashion, with Joe Biden emerging as the presumptive nominee.

But only days later, a much more serious problem than a crowded primary arose. It’s one thing to organize a convention when you don’t have the candidate. It’s another to have the candidate and not know if you can organize the convention.

A week after Super Tuesday, on Friday, March 13, Mr. Solmonese closed his Milwaukee office because of the pandemic and immediately moved back to Chilmark full time. His days started at 7 a.m. and ended after 11 p.m., with the scheduling of Zoom calls, phone calls and, of course, one very important roll call, packed in between.

“It was challenging,” Mr. Solmonese said. “At first, you’re functioning like it’s a snow day . . . and then the situation just kept getting worse and worse.”

The first move was to postpone the event. Two weeks later, Mr. Solmonese said it was clear that the team would have to shrink attendance. About a month after that, Mr. Solmonese made the decision to tell most delegates that they wouldn’t be able to come at all.

As the pandemic improved in Massachusetts over the summer, it surged elsewhere, including in Wisconsin. About a month ago, his team made the decision to have no one in the convention room. And then, two weeks ago, with the event looming, Vice President Biden himself made the decision not to travel. Everything had to go virtual. Mr. Solmonese traveled to Wisconsin. Almost no one else did.

“At each of those steps along the way, the many months worth of planning that we had done, had to be completely reimagined,” Mr. Solmonese said.

But his vision for the event remained largely the same. And without a traditional presidential summer, the event took on more significance, and that vision, in fact, became even more essential.

“I love a convention,” Mr. Solmonese said. “But if you think about a party convention . . . you are really televising the proceedings of the convention, and there are a lot of people in the arena who are very excited to be there, and everybody at home is just sort of watching. So, for us, it was a question of, how do we change that up? And how do we make it so that if you’re tuning in from home, it’s a more impactful experience.”

Speeches were no longer written with applause lines. Speakers were chosen not on the volume of their voice, but the power of their message. In a convention where no one could attend physically, Mr. Solmonese made it his mission that everyone could feel like they were included. Accomplishing party business and satisfying internal politics became secondary. Diversity became primary. And most importantly, the focus was shifted away from criticizing Donald Trump and onto telling Joe Biden’s story.

Incumbents only have to convince people to re-elect them, Mr. Solmonese explained. But challengers have to convince people to fire the incumbent and hire them instead. It’s a trickier needle to thread, especially when it has to be done fiber optically.

“To spend a lot of time bashing Donald Trump in an arena full of people, where the crowd is affirming what you’re doing, is one thing,” he said. “But in direct conversation with the American people, you need to do it in a different way.”

That way was through storytelling — through a 13-year-old with a stutter who Joe Biden had helped on the campaign trail, or a woman whose father had died of Covid-19, and was really telling a broader story about health care in America.

“The best way to talk to the American people about Joe Biden, is for people to tell their stories about Joe Biden,” Mr. Solmonese said. “And there’s no better story than a story about Joe Biden.”

And there are few better storytellers than the Obamas, he also said. While President Obama gave his speech from Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Michelle Obama gave her speech from the Vineyard. Mr. Solmonese said it was important to him that people spoke from locations that made them comfortable. For Ms. Obama, that place was the Island.

“Those were very different speeches than they would normally give,” Mr. Solmonese said about the Obamas. “The cadence, the flow, that was all designed to be an intimate conversation with people. And of course, what is so extraordinary about Michelle Obama is that she just knew exactly what she needed to do, and did it in the most powerful way.”

Mr. Solmonese said the most nerve-wracking bridge to cross during the production was a literal one — the panoramic shot above Alabama’s Edmund Pettus Bridge at the beginning of the virtual roll call. The roll call involved continuous live-streams in all 57 states and territories, a difficulty he underestimated.

But other difficulties that normally plague organizers — like having to jockey with celebrities and big-ego politicians for limited stage time — were mostly non-existent for this convention.

“I had a standard answer for most people,” Mr. Solmonese said. “Which was, this year, Bill Clinton is getting five minutes. That put everything else in perspective.”

He returned to the Island Sunday. He’s barely left Lucy Vincent Beach. Looking back on the experience of the past year, he felt the pandemic had finally made it possible for the convention to focus on the inclusivity of stories. He was simply thankful he had the opportunity to help Americans listen to them.

“It’s a thing that had never been done before,” Mr. Solmonese said, speaking about the virtual convention. “So last Friday, when I woke up, it was sort of surreal . . . my desire was for it to be more impactful, that we do a better job telling a story and delivering a message. And I think we had no choice but to do that, because of the fact that all we were left with, right, was the opportunity to tell a story.”

Comments (22)

Comments

Comment policy »