Teenagers and young adults on Martha’s Vineyard face a lack of educational and career opportunities that puts at risk not only their own future success, but that of the greater Island community, according to a report presented Monday by a team of graduate students from the University of Massachusetts medical school.

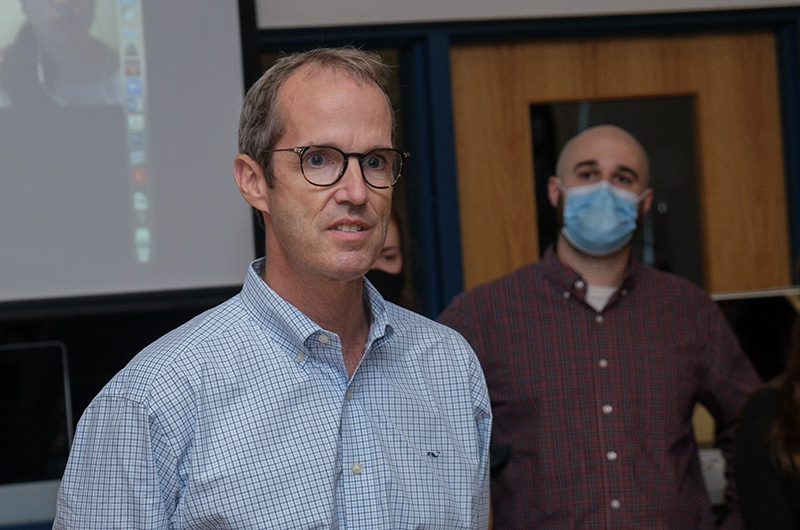

“The population on Martha’s Vineyard is aging, and there is a huge need for youth to . . . take over the existing businesses here,” said David Runyon, one of eight future doctors and nurses in the medical school’s Rural Scholars program who spent the previous 10 days living on the Vineyard and interviewing scores of Island residents.

“We spoke to many employers who expressed the need . . . to find people to employ,” Mr. Runyon said.

But with no community college, limited access to job training and an ever-worsening housing crisis, many young Islanders are likely to leave the Vineyard or slip through the cracks into substance abuse, mental illnesses and homelessness, according to the report.

“Every single interview we had, somebody mentioned housing,” said Brian Nickley, another member of the team.

In past years, Rural Scholars teams have examined Islandwide health issues including homelessness, aging, reproductive health care and substance use disorders.

This time, at the request of community education provider ACE MV, the future health care providers focused on conditions for Islanders aged 16 to 26 who may be disconnected from the larger Vineyard community.

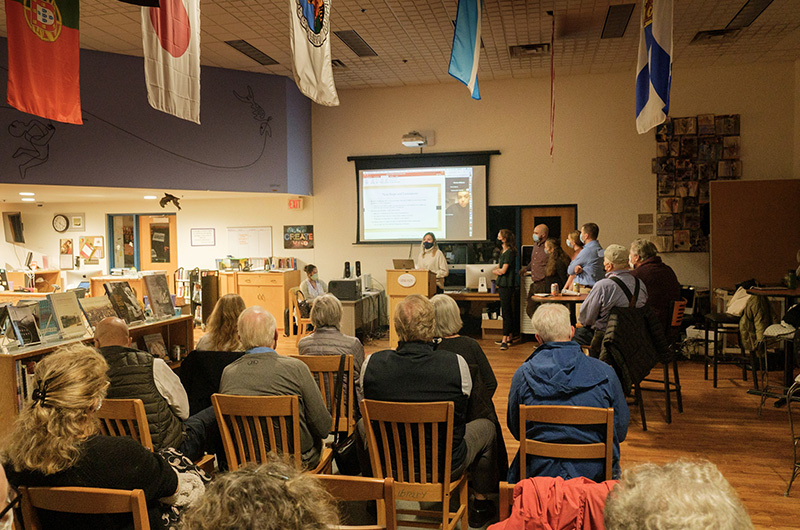

“The young adult population is one of the least served on Martha’s Vineyard,” ACE MV executive director Holly Bellebuono said, as she introduced the UMass team to about 40 people who turned out for Monday’s presentation in the regional high school library.

Youth is also the least-understood part of the Island community, said Dr. Dan Pesch of the Dukes County Health Council, which selected ACE MV as the scholars’ host this year.

“Sixteen- to 26-year-olds have eluded us in all the prior studies,” Dr. Pesch told the audience Monday.

Even the UMass team, dedicated to learning more about this age group, were only able to speak with 13 young Islanders among the more than 65 they interviewed last month.

They also fell short in surveying the Wampanoag community, interviewing only two tribal members during their storm-plagued Vineyard residency, the students said.

But the conversations and focus groups over the 10-day stay yielded some bleak assessments of the options for young people here, presented in a series of direct quotes from Islanders in the study:

“I know that my children will not be able to live here.”

“There are plenty of jobs, but they can’t afford to live here.”

“We’re graduating too many kids without options.”

“The older generation doesn’t like change.”

Yet change is needed if the Vineyard is to retain and cultivate its much-needed rising generations, according to the Rural Scholar report, which included an array of recommendations for improvement.

While the regional high school generally received good marks from the graduate students for its supportive, if small, counseling staff, the shortage of mental health providers on the Island is reaching crisis proportions, the scholars said.

“There needs to be a focus on attracting more behavioral health specialists, particularly those clinicians who have experience serving the youth,” Mr. Runyon said.

“We’re also recommending that the high school consider funding a full-time position for an advanced behavioral health clinician,” he said.

“We commend them for taking the steps to bring somebody in on a part-time basis, especially someone who is bilingual, and I think that’s been a really valued resource here, but our opinion is that there’s enough demand and enough need to support somebody in that position on a full-time basis,” Mr. Runyon said.

Tele-medicine is not an adequate alternative to in-person counseling for the 16-26 age group, Ms. Bellebuono said, stepping in to answer a question from the audience.

“A lot of the disconnected youth and young adults that we’re trying to reach . . . they’re truly disconnected. They don’t have a home, necessarily. They couch surf from family to family. They may have a job, but it’s a temporary or seasonal job or they may bounce around to seven or eight employers in the course of a year,” she said.

“Just thinking about tele-health as an option, they really don’t have a grounded center from which they can approach resources such as that, so reaching them and offering these services is much more difficult.”

The UMass team also recommended a shift in culture at the high school — among families and educators alike — away from the primacy of college as the default post-graduation goal.

The medical students also suggested the concept of a gap year after high school, to allow young graduates to firm up social skills that Island living does not always encourage, but which are important in careers and college.

“It was voiced frequently [in interviews], and even from students . . . that they just weren’t quite ready,” said team member Sabine Shaughnessy.

Mentorships and apprenticeships with Island companies should be bolstered, and pathways to work are needed for undocumented youth as well, Ms. Shaughnessy said.

“There needs to be, without a doubt, paid opportunities for undocumented students to participate in work study and co-op programs,” she said.

Although specific numbers for the Vineyard were not available, statewide the Brazilian population increased by 27 per cent between 2008 and 2017, according to the Rural Scholars report.

Among other recommendations, the UMass team urged a summit of youth-serving organizations modeled on the Vineyard’s Food Equity Network, members of which were included in the study interviews.

“We thought that was a wonderful model,” Mr. Nickley said.

Ms. Bellebuono said the Rural Scholars presentation will be made available to the community through ACE MV.

“We definitely anticipate continuing this conversation,” she said.

“We do count on Ace MV to carry the torch on this,” Dr. Pesch said.

Comments (4)

Comments

Comment policy »