The Gazette’s files of yellowed article clippings and fading typewritten letters, each neatly signed “Eisie” in upright black letters that could pass as calligraphy, show a man of unfailing manners and attention to detail, but of course it is the pictures that tell the story. The late Alfred Eisenstaedt cared deeply about the Vineyard, an affection most clearly expressed on film, in black and white (“I know it looks better than color,” he said, allowing that “flowers and fashion should be in color.”)

Two years after European-born Mr. Eisenstaedt arrived in the United States, he arrived on the Vineyard. The slight man who became a giant in his field came here in 1937 aboard the powerboat captained by his boss, Life Magazine publisher Roy Larson, and later reported his first impression: The view of the Gay Head Cliffs was “so unbelievably beautiful that it made my eyes fill with tears.” And so in the latter half of the century, Mr. Eisenstaedt — or Eisie, as he was so widely known — spent most of the year traveling the world as the pioneer of what we now call photojournalism, and each August on Martha’s Vineyard.

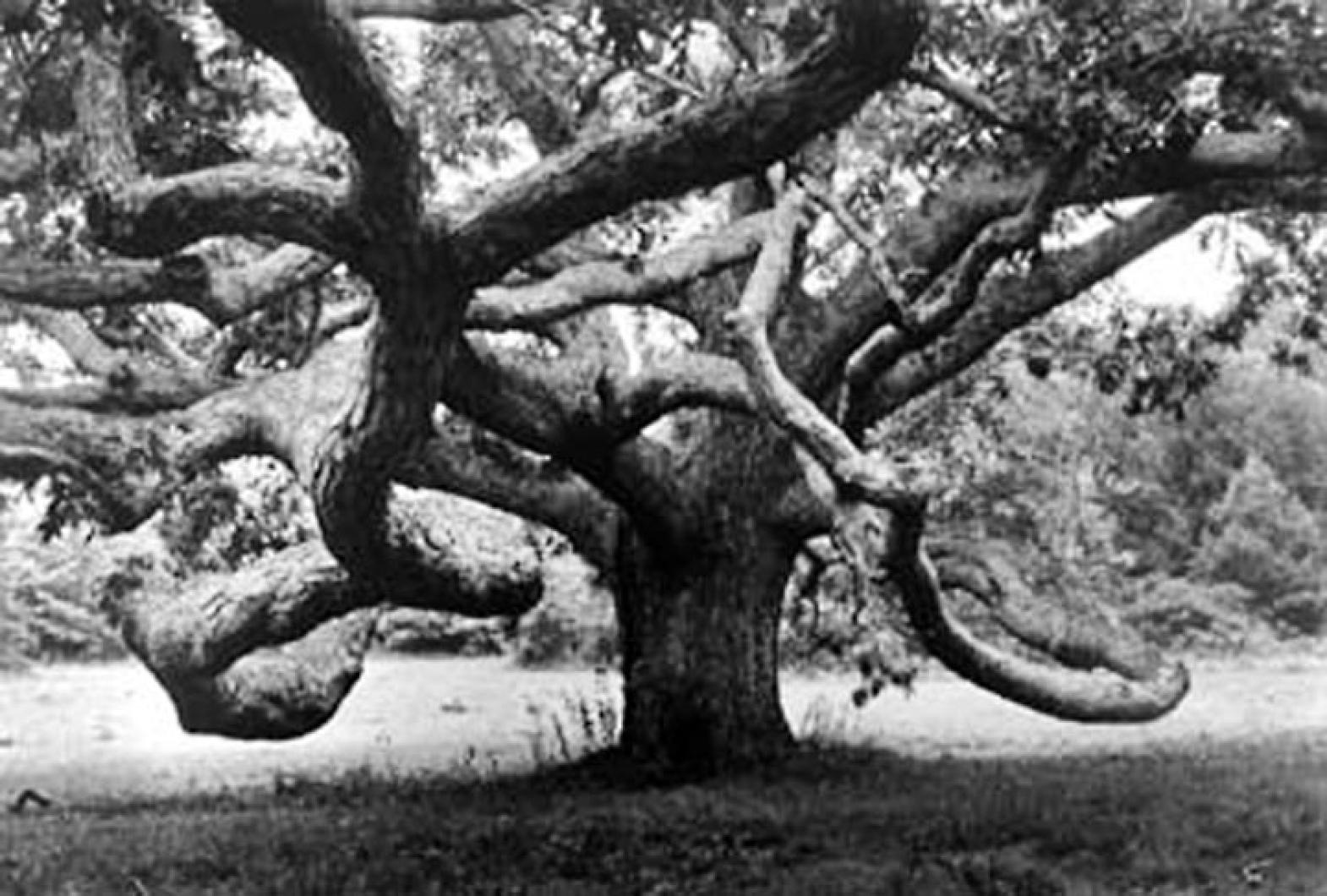

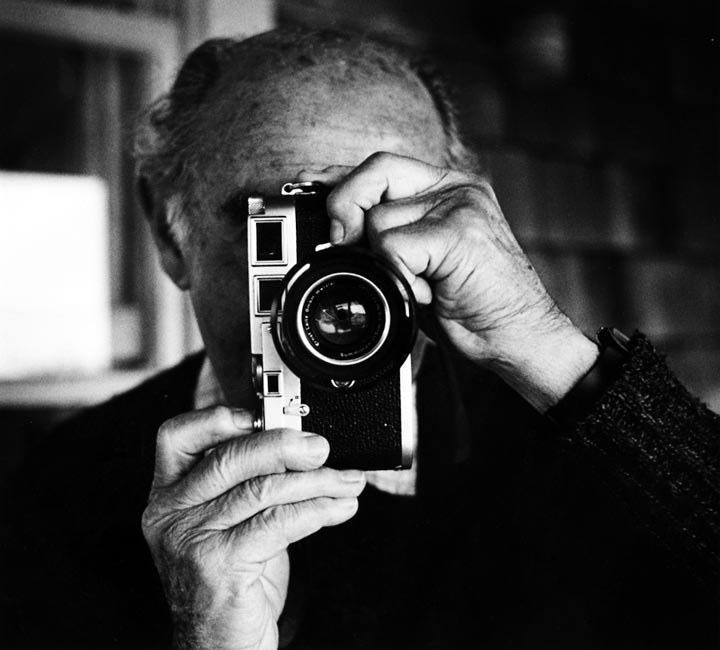

Here too he carried his Leica — often two, one with color film, one with black and white — and though he was on vacation, he kept shooting. The same gentleness, patience and genius that saw him lauded as the photojournalist of the century also won him lifelong friends and admirers on the Island. One of those is Chris Morse, who with his wife now owns the Granary Gallery where Eisie’s work was exhibited. On Sunday Mr. Morse will present a free talk, Remembering Alfred Eisenstaedt at 2 p.m. at the Vineyard Haven Public Library, spanning his classic Life images (including one where he stooped beneath a puppet show stage to capture the children’s faces when the dragon appeared) and his Vineyard work (including a shot of the great oak tree in North Tisbury, an image Mr. Morse says “captures the essence of the tree rather than a piece of the landscape.”)

While still in high school, Mr. Morse began working at the Granary. He would take cases of books to the Menemsha Cottage where Eisie and his wife, Kathy, always stayed, and visit while the photographer signed them. The playful Eisie would make a game of it, timing himself; how many books could he sign in an hour? Their professional and personal friendship would develop over more than a decade. So on Sunday Mr. Morse will show Eisie’s photos while telling stories of his life. Perhaps it will not be unlike the much-anticipated slide shows Eisie himself hosted many summers here.

Henry Luce said it was Eisie who first proved that a camera could deal with an entire subject, not just a moment in time. So it was with the subject of the Vineyard, which was his subject more than any other place. He lamented the changes in taste in photojournalism over the course of his lifetime (he recalled an early assignment to shoot Roosevelt Hospital where the only direction given him was “I don’t want to see any blood,” complaining that later blood would become the preeminent feature of his trade.) Likewise he lamented about the Vineyard in 1975, “Progress is spoiling everything.”

This from a man who began his career with 240 pounds of equipment in tow (yet never did that dampen his dapperness; his tuxedos had reinforced pockets for the steel holders that held the glass plates for his images). He became the master of the 35-millimetre lens and the chronicler of world and national figures and events.

Eisie himself said, “They can send me into an empty room, and I can do a story.” Here, where he began staying at Gay Head before electricity had reached it, he found much more to occupy his lens. And refreshingly, or nostalgically perhaps, always it was the best of the Vineyard. “I don’t want to show the bad side of life,” he said.

Comments

Comment policy »