A honeybee visits between 50 and 100 flowers during one collection flight from the hive. On its flight from blossom to blossom, honeybees transfer pollen from plant to plant, fertilizing the plants and enabling them to bear fruit.

But what if the fruits and vegetables we don’t even think twice about buying were no longer available? Due to a phenomenon called colony collapse disorder, disappearing bees means disappearing fruit is an increasing possibility.

Vineyarders learned more about this crisis and what they can do to help at the Bee My Honey Brunch hosted by Slow Food Martha’s Vineyard last Sunday at the Chilmark Community Center. While there is still some controversy over the cause of the disease, organic beekeepers believe systemic pesticides poison the fuzzy pollinators when they go to feast on the pollen. These pesticides are mainly used on monoculture farms, but invasive parasites, viruses and food supply are also considered to be contributing factors to the decline.

After feasting on a honey-based breakfast of chicken and waffles, coffee cake, honey tea, couscous, Mermaid Farm yogurt with a berry honey sauce and ginger honey scones, the sweetness continued when attendees learned the Vineyard has been mostly spared by the disorder.

“We are so lucky here because we don’t have farms that grow one crop,” said Randi Baird, a beekeeper and founder of the Island Grown Bees program. “Most of our family farms on the Island grow a variety of crops and that’s one aspect of colony collapse disorder.”

Commercial honeybee operations are used to help pollinate crops, sometimes traveling across the country to increase production, and make up one out of every three bites of food. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, bee pollination is responsible for $15 billion in added crop value. But as a result of the disorder, it is estimated one third of the honeybee colonies in the country have disappeared.

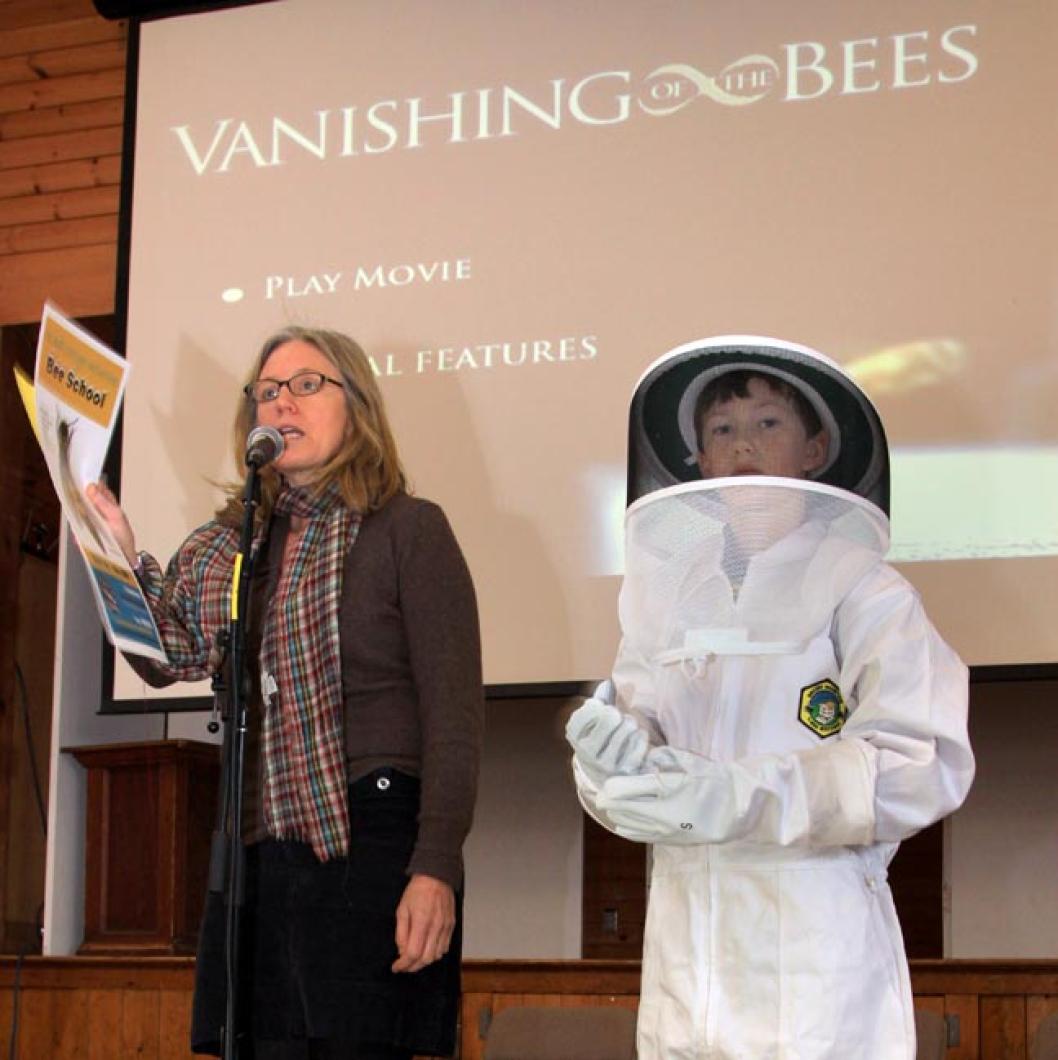

Pennsylvania beekeeper David Hackenberg first noticed the crisis in 2006 when his bees began disappearing and dying off. In a screening of Vanishing of the Bees at Sunday’s event, Islanders learned Mr. Hackenberg’s story and how he catapulted the disorder into a national discussion. Since its discovery, the disorder has been found in 35 states.

Vineyard Haven beekeeper Tim Colon has 50 to 60 hives, produces 500 pounds of honey a year and has bees stationed at Morning Glory Farm in Edgartown and North Tabor Farm in Chilmark to assist in pollination. Neither Mr. Colon nor Ms. Baird have seen effects of the disorder on the Island; fungi and Vero mites have been the only pests they’ve dealt with.

“I have not seen it, doesn’t mean they’re not there,” Mr. Colon said. “We are lucky in the way that we are a little bit isolated from commercial bees and a lot of bees from the Island have been coming from Everett [Zurlinden] for the last year or so, and he’s pretty good about keeping an eye on his bees.”

Mr. Zurlinden is a Rhode Island apiarist who will host a bee school April 1 to April 3 for people interested in becoming beekeepers.

Tips for keeping the honeybees close to home include putting in plants that attract them, leaving a patch of wild growth for them to feast on and eliminating use of pesticides. One bee lover pointed out that chemicals on lawns and tree treatments are some of the most notable pesticides used across the Island.

Current beekeepers looked for answers to keeping their bees around, and Ms. Baird, Mr. Colon and Owen Ackerman recommended sprinkling powdered sugar on the hives and rotating the comb so it doesn’t become infected with unwanted chemicals.

“[Colony collapse disorder] was originally a commercial disease,” said Mr. Ackerman, who has an apiary in Norfolk. “We didn’t really see too much of it. We’re seeing some of it this year. I lost a hive; it’s kind of questionable to lose a hive in the middle of January when there were bees there in December, a healthy hive.”

The majority of the disorder is seen in large commercial operations. As a result of the disorder, Australian bees were shipped to the United States to help replenish the necessary pollinators, but as of last month the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service banned the importation of honeybee queens and package bees.

At a honey tasting table, the commercial honeys drew the lowest marks. Andy and Susan’s honey tasted like the honey sticks kids sneak into their parents’ shopping baskets (they sell their honey at a roadside table on Middle Road). Ms. Baird described the Katama honey as “fall flowers,” while the Island Bee Company honey tasted like a spring arrangement.

“I think living on Martha’s Vineyard is a really unique opportunity to keep bees for political reasons, for personal reasons and personal enjoyment,” Ms. Baird said. “I started beekeeping just because I read a book, The Secret Life of Bees, and I said to myself I had to become a beekeeper. Right now there’s a lot of interest in beekeeping because of Slow Food and other organizations that realize there’s a real importance to promote beekeeping. And as individuals you can do something about that.”

For more information on beekeeping, the Martha’s Vineyard Garden Club is hosting Howland Blackiston, author of Beekeeping for Dummies on March 5 at the Wakeman Center in West Tisbury. To register for the bee school, visit islandgrown.org/pollination.

Comments

Comment policy »