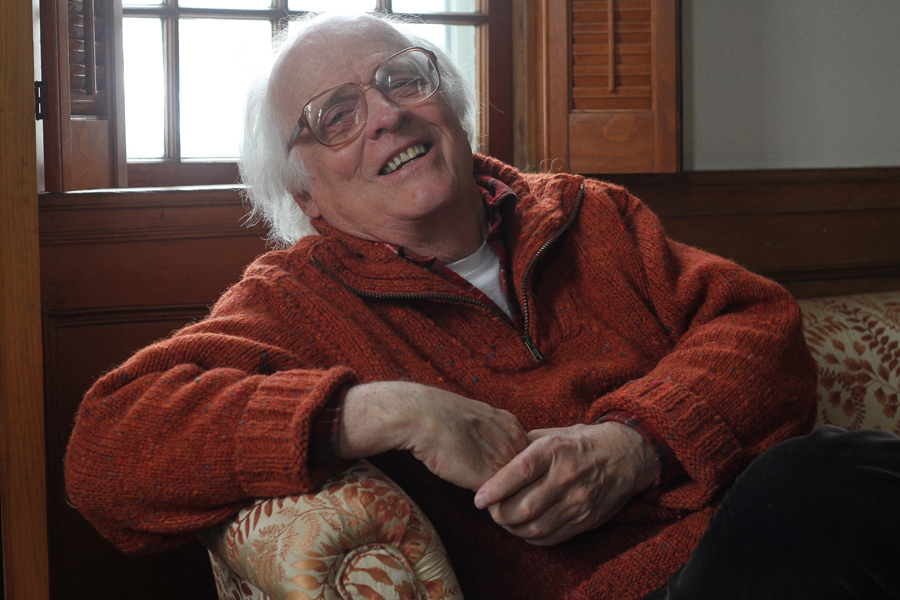

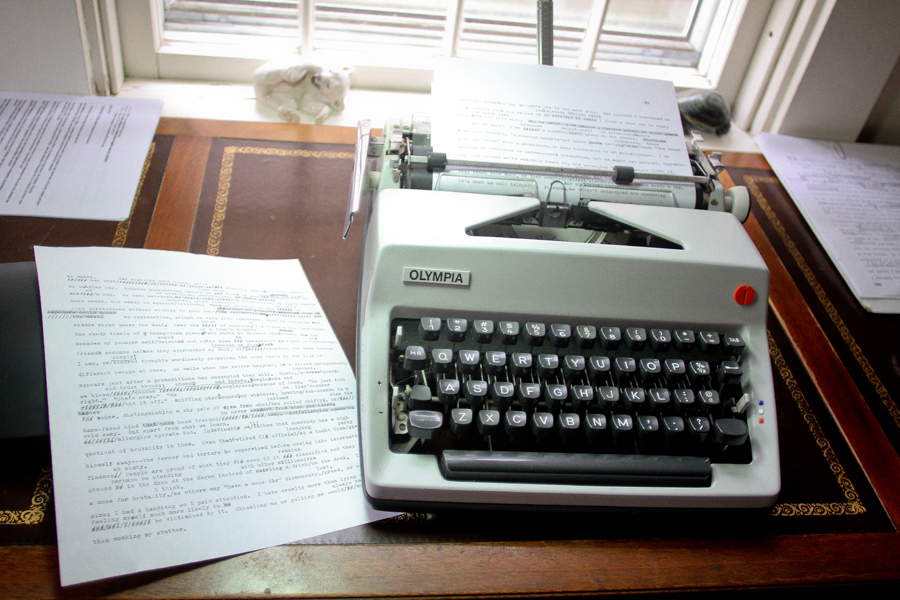

In his small office with wide floorboards and rippled glass windows, Edward Hoagland sat in front of his bookshelf at his 18th century Edgartown home earlier this week. Behind him on his desk was a 1968 Olympia typewriter, the ink still wet from the essay he had been working on earlier that morning. Old New Yorker magazine covers with circus scenes on them decorated the walls, a few African masks hung above the windows and classical music played in the background.

Mark Twain, Franz Kafka and Thomas Mann jumped off the spines of the classics that filled one of his many shelves, but Mr. Hoagland was looking for one in particular.

He pulled out a copy of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden and read the personalized inscription from the author of the introduction, John Updike: “For Ted Hoagland, our own Thoreau.”

“I wanted to be a writer partly because I had a talent for it, partly because I stuttered 30 times worse than I do now. I could hardly speak,” Mr. Hoagland said. “My only outlet was writing. I did have a few friends [including Mr. Updike] but I didn’t have the ordinary outlets socially that people have who are not handicapped.”

Mr. Hoagland, 78, writes about what he loves — traveling across the world, the two summers he spent working for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, and the grittiness of city life, to name a few. But when it comes to his essays on nature and the human connection, it’s as though the reader is brought into a Pieter Breughel painting and confronted with the complexities of the natural and human worlds.

In Mr. Hoagland’s latest collection of essays, Sex and the River Styx, he meanders his way through intricate reflections on relationships, aging, life and nature.

Mr. Hoagland is proud of his life’s work, which includes 21 books, editing the Penguin Natural Classics Series and writing countless essays and short stories. He completed his first novel, Cat Man, while at Harvard in 1958, but he prefers the faster gratification of short form writing.

“I would publish [essays] in the Village Voice, which was only a few blocks from my apartment in New York, so I had the joy of turning in something on Monday and seeing people on the subway and Staten Island ferry reading it on Wednesday The rewards were immediate in terms not just of ego but in terms of communicating, which is why people write,” he said.

“I mainly work from my memories at this point, I don’t need to add anything to my life list,” he said. “I’m glad I found my genre essayists work in present tense for the most part and your genre is essentially talking directly to other people in an ordinary way, and with a handicap, you have a leg up as an essayist because you long to talk to people.”

Mr. Hoagland has lived a life without regrets. After two marriages, circus life and learning to “trust everybody a little and nobody a lot,” the greatest sadness he’s had comes every spring when he hears fewer bird songs.

“I do think I’m an Emersonian in that tradition, which means that I believe all life is essentially holy,” said Mr. Hoagland. “I do look forward to death as a recycling going back to the ocean, where we all came from. Being reconstituted into whatever life force or form of energy. I don’t believe in reincarnation as a gnat or a dog, I’m not a cynic in that sense. I have a life-affirming center in my beliefs, but I’m heartbroken by what is happening to nature and therefore ultimately what will happen to us as well.”

Mr. Hoagland has crawled into the cages of panthers, travelled to the Northwest and Alaska nine times and, when he was 17 years old, lunched with John Steinbeck, but the most powerful experience, he recalls, came in 1993 when he visited a refugee camp in southern Sudan.

Mr. Hoagland was traveling with a nonprofit aid group and visited three refugee camps, where 100,000 people had not received an aid delivery in three months. There were no more songbirds; the insects, the rodents — everything had been eaten. With his fair skin and white hair, Mr. Hoagland was thought to be a king, or better yet a representative from the United Nations. The children were told he was there to save them, and they clung to him as their savior.

“I was just a wandering freelance journalist,” he recalled. “It was a scalding scene.”

Nearly 20 years later, Mr. Hoagland has had time to pause and reflect on these experiences. When he’s not writing during the day he enjoys outtings to Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary and the Fuller street beach, or attending the foreign film series at the Edgartown Library. Mr. Hoagland is an off-season-only Vineyard resident; he spends summers at his home in northern Vermont with no electricty. He lives by the sun.

Aging has allowed him to be realistic about the future. There’s no formula to save the planet or our humanity, he said, and sitting at a computer screen archiving history is not sufficient for human survival.

His greatest survival tip might be the simplest. Love is a cliché, he said, butclichés tend to have a core.

“You work best and function best in our lives if we are operating from love,” he said. “It’s not something you consciously flick on like an electric switch, but I’ve written about what I love and of course that’s also helped to raise a family or have a circle of friendships. So love is a secret of life.”

Edward Hoagland will discuss Sex and the River Styx tonight, Friday, April 29, upstairs at the Bunch of Grapes on Main street in Vineyard Haven.

Comments

Comment policy »