Caveat emptor: If you watch this thoroughly engrossing film, you may very well recognize as-yet-undiagnosed symptoms of learning disabilities or other psychological variations in your own family.

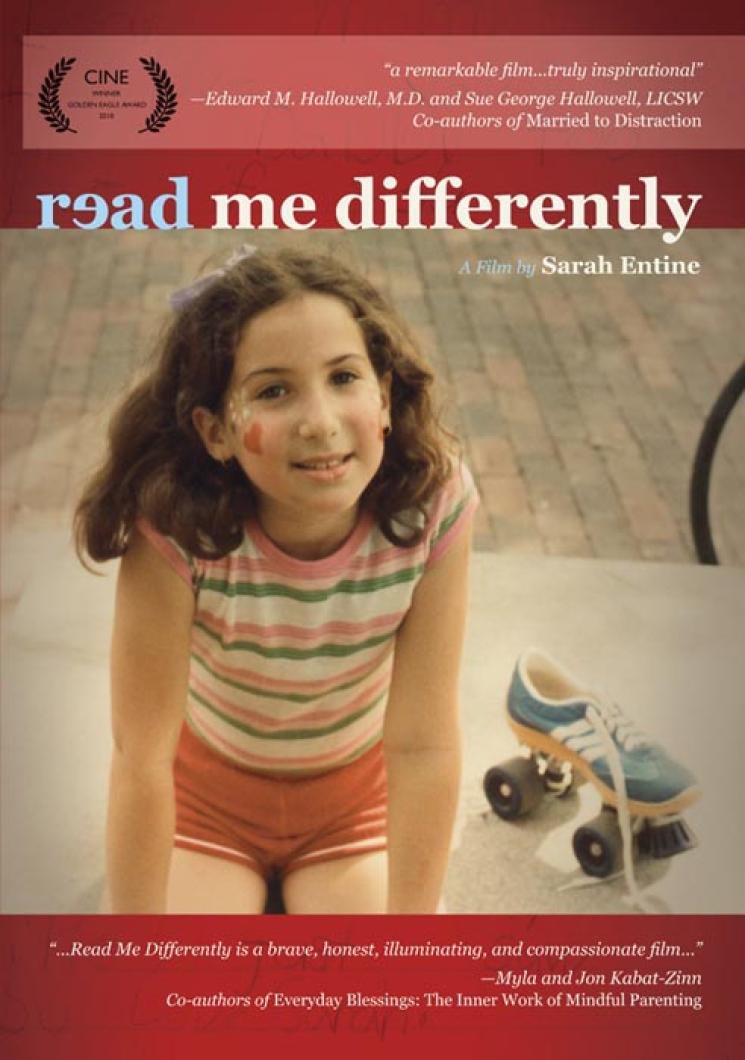

Sarah Entine, frequent visitor to Martha’s Vineyard, whose mother, Jean Entine, has lived since 1996 in Aquinnah, has made a film about her discovery — in graduate school, of all places — of her own phantom case of dyslexia and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. “I opened a can of worms,” she admits in the film, called Read Me Differently.

The can involved her grandmother, Sylvia, first glimpsed in her Memphis home strewn with papers, newsletters and photographs scattered over every available surface including the floor.

“Everybody visiting Grandma tries to get her organized,” narrates Sarah.

We see the two of them in the midst of the chaos. Sylvia, 94, picks up a page and reads out loud an article about storms. It’s not that the topic fails to fascinate, but Sarah knows how easily Grandma is sidetracked. “Let’s organize,” she coaxes.

Sylvia is undeterred. “Maybe I need paper clips,” she announces.

Sarah’s father, Alan Entine, attended Middlebury College and proved a Phi Beta Kappa and valedictorian. Sarah’s mother, Jean Entine, also was academically more than proficient. But Grandma Sylvia’s growing up years in Memphis yielded a different story in a time when learning disabilities were not only undiagnosed but essentially unknown:

Sylvia reveals that her parents wanted her to blossom into a southern belle, sweet, pretty, charming and anything but smart. “School was hard and boring. I had such a difficult time reading that I thought there was something wrong with my eyes. When I went to see a doctor about my vision, he told me college probably wasn’t the right choice for me.”

She tried college briefly, then dropped out to get married.

Jean says that her mother’s conversation always flummoxed her. “She starts every story in the middle. She repeats herself and travels through four different stories to arrive at the place she started and, more often than not, she forgets what she originally meant to say. I go directly to being impatient.”

Clearly these tendencies are more pronounced with age, but Jean recalls being bedeviled by her mother’s circumlocutions from a very early age. Friction attended most of their conversations.

Jean moved to New York after her marriage to Alan and they had two girls, Jennifer and Sarah. Jennifer met the parents’ high expectations, but Sarah presented learning problems from the minute she entered school.

“We had no labels for it then,” Sarah narrates in the film, “but I had a phonological disorder.”

In other words, she was unable to recognize sounds from letters viewed on a page. From second grade on she worked with a tutor, a psychologist whom she revisits in the documentary.

By the second grade, Sarah’s parents had divorced and Jean moved with her two young daughters to Cambridge. Sarah reports that schools by that time — in the mid-70s — had become more open to differences in learning styles, and the second grader found herself more accepted at school than at home.

Her high-achieving mother put her through the paces of reading children’s books out loud. “Reading was torture for me,” admits Sarah.

Both her parents believed she simply needed to apply herself with greater intensity. “Try harder!” her mother would urge her.

Meanwhile Sarah interpreted Jean’s disapproval as withholding of affection, a not-uncommon response from children with learning disabilities supervised by high-achieving parents. The hurt disclosed itself in some of Sarah’s early essays written in a child’s scrawl: “If you like me, just say so.” “I hate you and I don’t care very much, Mommy. Sarah.”

Sarah did apply herself to the best of her ability and her reward was acceptance into Grinnell College in Iowa. All the same, studies proved a problem: “I was 285th in a class of 321.”

After she graduated, she returned to Cambridge and took a job in a flower shop. She found to her delight she had a talent for flower arrangement. She was no longer required to think in a linear fashion, something that never came easily to her. Instead her creative juices flowed and she reveled in the changeover to a right-brain activity. “I finally felt good about something I was doing.”

She worked at the flower shop for a full two years. Her mother expressed concern about this particular transition: “I worried about Sarah: Had her menu become too small?”

Sarah felt her parents’ academic pressures mounting but, more importantly, she may have unconsciously gone in search of her own psychological issues. What better place to discover them than in a graduate school in social work?

For her internship, she found herself in a conference room with a crowd of other students. The phones rang constantly, people worked with open notebooks as they ate and conversed: Sarah felt bushwhacked by all the extra stimuli. She called her mother and her older sister and their advice was the usual, “Buck up” and “Try harder.”

One day Sarah opened the diagnostic manual, the DSM IV, and she found the section on learning disorders. All of a sudden everything came clear, starting with her grandmother’s paper chaos, and her stories that began in the middle and then went helter-skelter in every direction.

Read Me Differently is about Sylvia, Jean and Sarah’s on-camera attempts to connect with one another. Grandma steals the show with her Lucille Ball antics. At one point her daughter and granddaughter arrive to find her Memphis home swept clean. It turns out she stashed all her papers and photographs under the heavily skirted bed.

“Grandma has all the attributes of ADD,” says Sarah, but at the same time the nonegenarian gets the others to laugh about it. Her own coping technique has been humor: Life with Sylvia has been, among its vexations for the linear-thinking Jean, a laugh-out-loud riot for everyone concerned.

Sarah and Jean attempt to cross the bridge of their differences, although Jean is sometimes quick to react with anger, as when Sarah questions her mother’s irritation with her own mother reemerging when her daughter, too, shows signs of learning disarray. Jean snaps, “I’m a daughter to one and a mother to another!”

Yet in a future conversation Jean says with profound compassion for all three of them, “How much we’ve overcome!”

The ground-breaking documentary Read Me Differently will debut on Monday, Sept. 19 at 10 p.m. on WGBH in Boston (PBS, channel 2). A second screening for Vineyard audiences will take place at the Vineyard Haven Public Library on Oct. 11 at 7 p.m.

Comments

Comment policy »