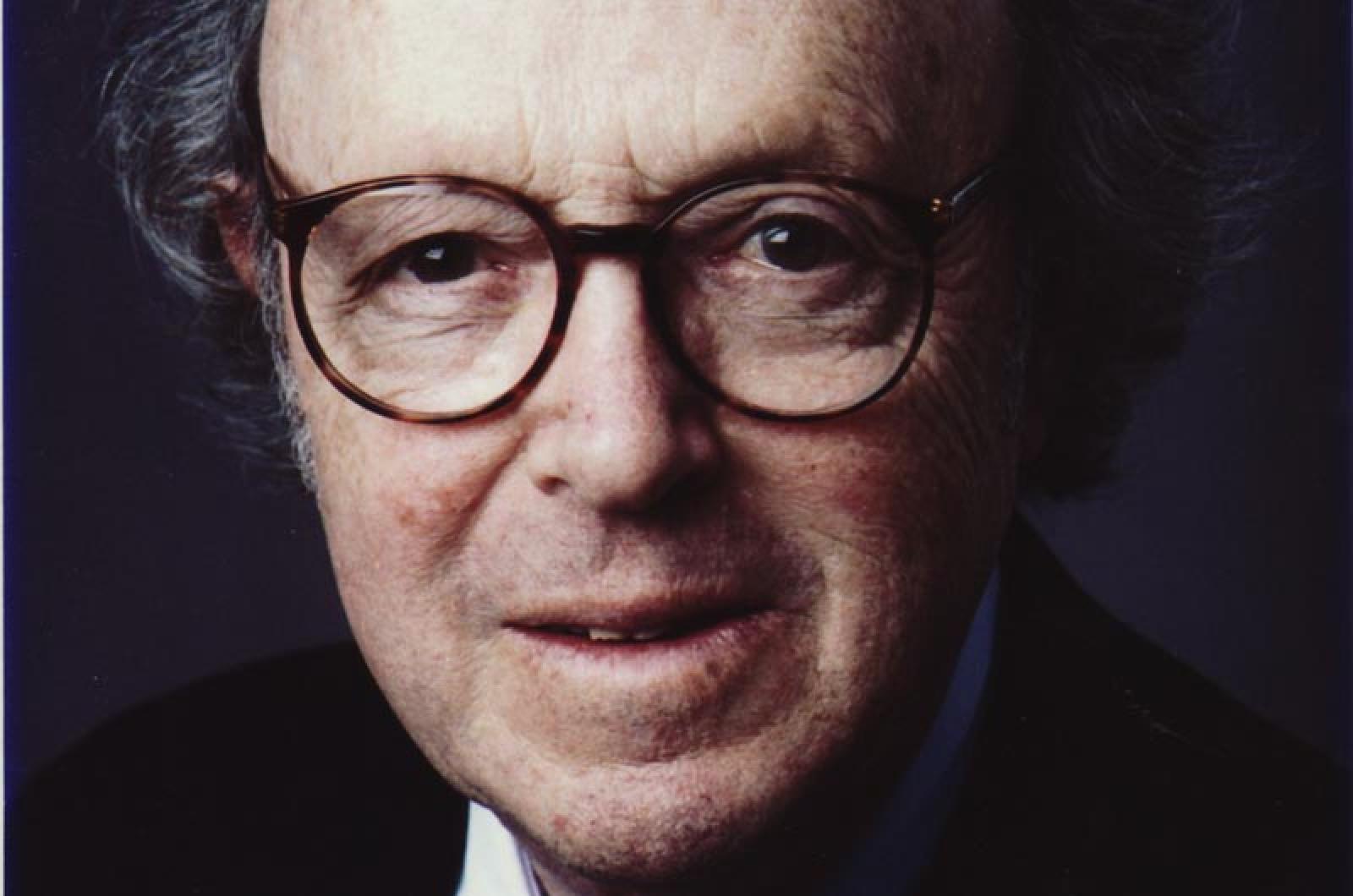

Anthony Lewis, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author who brought his passion for justice and free speech to a career spanning more than a half century, died Monday. A long-time seasonal resident of West Tisbury, he was 85.

Mr. Lewis died of complications of heart and renal failure at his Cambridge home, said his wife, Margaret H. Marshall, former chief justice of the state Supreme Judicial Court. Private services were held Wednesday, the day he would have turned 86.

A memorial service is planned for 3 p.m., May 23, at The Memorial Church at Harvard University.

Mr. Lewis’ outsized career earned him two Pulitzer Prizes, print journalism’s highest honor, as a reporter for the Washington Daily News in 1955 and for the New York Times in 1963. He ultimately worked at the Times for nearly five decades, serving as a reporter, foreign correspondent and columnist.

“Tony was a very, very special person,” said Edgartown attorney Ronald H. Rappaport, a longtime friend. “He loved the Vineyard, the tranquility and getting away from it all. I regard it as one of my great fortunes in life to have become friends with him. He is one of my heroes.”

Family members say Mr. Lewis first came to the Vineyard in 1950, to visit his aunt and uncle, and began renting in 1956, eventually buying a camp on Deep Bottom Cove in 1962. He and Justice Marshall built a house further down the same road in 1994.

Over the years, Mr. Lewis wrote and spoke about his deep affection for the Island, its sense of community, civic engagement and natural wonders.

His professional life seemed to be balanced by the summer rhythms here, which included beachcombing, sailing, collecting seaweed for his garden and foraging for beach plums, wild grapes and chokecherry to make his homemade jellies. “In many ways, the Island was as much home as Cambridge,” said Justice Marshall. “He had a very deep connection” to the place and its people.

Born March 26, 1927 in New York city, Mr. Lewis graduated from Harvard College, where he had been an editor for the Harvard Crimson, in 1948. He joined the Sunday Department of The New York Times in New York, and later The Washington Daily News, an afternoon tabloid, with a stint in between working for the 1952 presidential campaign of Adlai Stevenson.

At The Washington Daily News, he earned the national reporting Pulitzer Prize for a series of stories that championed the cause of an employee of the U.S. Navy who had been dismissed as a security risk. The Navy later admitted it had committed an injustice and restored him to active duty. “This is in the best tradition of American journalism,” the Pulitzer citation said.

In 1955, he returned to The Times to work in the Washington bureau under James (Scotty) Reston (who, with his wife bought the Vineyard Gazette in 1968). Mr. Reston eventually assigned him to the Supreme Court, also sending Mr. Lewis to study at Harvard Law School as a Nieman Fellow, focusing on constitutional law and the court.

One of Mr. Lewis’s signature accomplishments was to bring a heightened quality of reporting and analysis to the Supreme Court. At the time, most press coverage was considered to be shallow, sometimes wildly inaccurate; one commentator suggested that no newspaper would dare staff a baseball game as poorly as it did the court.

Mr. Reston had been hearing complaints about coverage from Justice Felix Frankfurter, who was skeptical that a reporter could quickly and accurately summarize the court’s complex decisions — until he read Mr. Lewis’ work, according to Mr. Reston’s 1991 memoir, Deadline.

“The next morning,” wrote Mr. Reston, “Justice Frankfurter called me at home. ‘I can’t believe what that young man achieved,’ he said. ‘There aren’t two justices of the court who have such a grasp on these cases.’ I never asked him the name of the judge.”

In an increasingly complex world that demanded reporters with specialized training, he wrote, Mr. Lewis had set a new standard. His second Pulitzer, in 1963, was for his reporting on the Court.

In 1970, Mr. Lewis landed one of the most prestigious, high-profile jobs in the newspaper business: a regular column on the Op-Ed pages of The New York Times. From there, his lucid, liberal voice was regularly heard for more than three decades — on matters of justice, free speech, politics, civil rights and foreign affairs.

“Tony was one of the great young lions in that period, and he could very easily have become the top editor of the Times,” said Alex S. Jones, himself a former Times reporter who wrote a history of the newspaper, The Trust: The Private and Powerful Family Behind The New York Times.

“I think he was more interested in writing than being an editor,” Mr. Jones added. “The way things evolved [he had] a spectacular career as a reporter and columnist.”

He authored several books and was awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal in January 2001 by President Clinton. “As a staunch defender of freedom of speech, individual rights, and the rule of law, he has been a clear and courageous voice for democracy and justice,” the citation said.

Mr. Lewis retained a life-long respect for the judiciary as an underappreciated linchpin of democracy. Two of the Supreme Court’s historic decisions from the sixties became subjects of his most widely praised books, which are still read by students of the law and journalism.

Gideon’s Trumpet, traced the legal journey of Clarence Earl Gideon, a small-time criminal, from his arrest and trial without a lawyer all the way up to the court’s decision in 1963 granting defendants a right to counsel, even if they could not afford one. (Years later, in a TV movie adaptation of his book, Mr. Lewis made a brief appearance on camera as “a reporter.”)

His 1991 book, Make No Law: The Sullivan Case and the First Amendment, unfurled the drama of a libel case that pitted segregation-era Alabama courts against the Times. In 1964, the Supreme Court overturned a verdict against the newspaper, and thus created more breathing room for journalists to write about public officials without fear of legal sanctions.

Mr. Lewis not only wrote about the law, he also lectured at Harvard Law School for 15 years. He also taught at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism for two decades.

On the Vineyard, Mr. Lewis and family did without electricity and a telephone at Deep Bottom Cove. After writing his column on a manual typewriter, he would drive up a long, bumpy dirt road to use a pay phone to call in his work, friends and family said. Later he sought out those neighbors with phones.

Ginny Jones of West Tisbury looked forward to those afternoons in the late sixties and early seventies when Mr. Lewis sailed his Sunfish across the cove to use her family’s phone. In a sense, she was the first to hear his take on the events of that tumultuous period of war, protest and social change.

“He was an extremely insightful, incisive, powerful writer,” she said. “It was kind of the highlight of my week. You always got his point of view, but he didn’t hit you over the head with it.“

He was a fierce advocate of efforts to preserve the Vineyard’s distinctive qualities.

In July 1969, for example, he lamented the proposed extension of a runway at the airport. In a statement published in the Gazette, he called the Island’s tranquility “that most precious quality of life. That is what brings people to Martha’s Vineyard and makes them so loyal to the Island. Just as you cannot be a little bit pregnant, you cannot tamper just a little bit with tranquility and have it left.”

He also valued the Island families he came to know in West Tisbury and appreciated virtually anyone else he encountered, from the moment he stepped off the ferry, said Justice Marshall.

“Tony was the least pretentious person I know,” she said. “He did not seek the limelight. He was interested in everybody he met. Everybody.”

In addition to Justice Marshall, who retired from the Supreme Judicial Court in 2010 to spend more time with Mr. Lewis, he is survived by three children, Eliza, David and Mia Lewis, all from an earlier marriage to the late Linda Rannells, and by seven grandchildren.

The response to his death this week has been overwhelming, said family members. While his views could provoke outrage, so many responded about how their lives had been changed for the better by his life and his work, said daughter Eliza Lewis.

“I’m not talking about a handful; I’m talking about hundreds of people . . . ,” said Ms. Lewis. “There are so many people who fall into this category of people he helped. It is just remarkable. It’s just been such a powerful reminder of how he was a tireless crusader for justice.” The family said contributions in his memory may be made to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 330 7th avenue, 11th floor, New York, N.Y. 10001.

Comments

Comment policy »