On a warm evening last week, people quietly linked hands around the Edgartown Lighthouse as the sun lowered over the houses and bell towers near the harbor. It was a spur-of-the-moment demonstration, using the simplest of gestures.

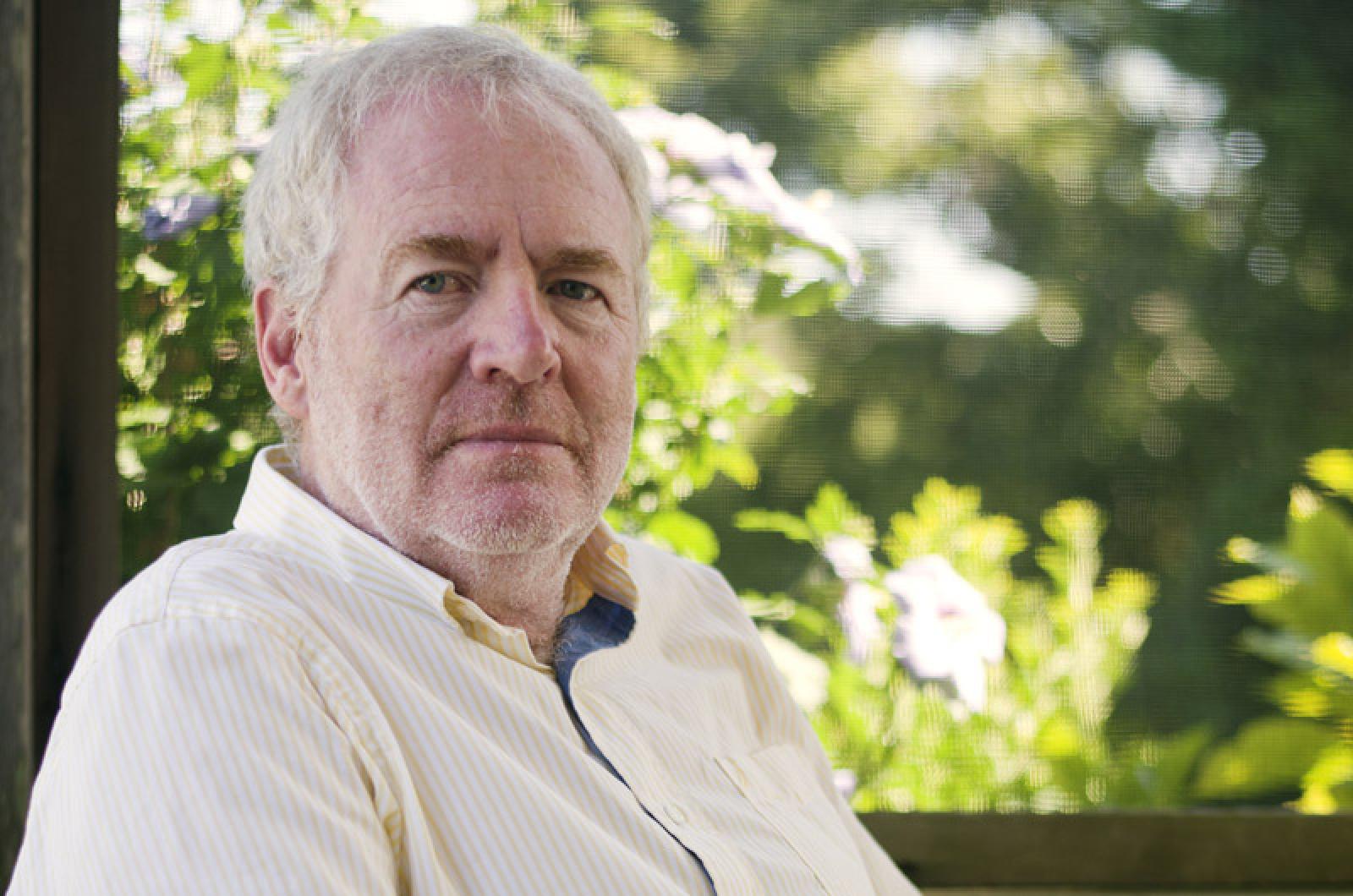

Bill Shipsey, founder of Art for Amnesty, a program of Amnesty International, had organized the circle in advance of a major human chain project in Italy this weekend. In August, he had done the same thing with his family and friends around the Gay Head Light at the opposite end of the Island.

The Gay Head event was the first of many around the world leading up to the 6,000-person human chain that will form in the Dolomites on Sunday, a joint venture between Art for Amnesty and Amnesty International in Italy, in support of refugees around the world.

Last Thursday, a human chain formed around the Columbus Monument in Barcelona. Others groups have assembled around redwood trees in Santa Cruz, Calif., and in Brussels. Following the Vineyard’s lead, people in Dublin recently linked hands around the South Bull lighthouse at the entrance to the Port of Dublin.

Mr. Shipsey, who lives in Ireland and summers in Katama, recently commissioned a large tapestry for Ellis Island, on the 40th anniversary of John Lennon receiving his green card (the outcome of a long legal battle with the U.S. government), and to highlight Amnesty’s Open to Syria Campaign, which calls on western countries to accept the most vulnerable Syrian refugees.

Longtime Amnesty supporters Bono and The Edge, of the band U2, along with Mr. Lennon’s widow, Yoko Ono, and others, were on hand in July to unveil the tapestry, which shows Manhattan as a yellow submarine with Mr. Lennon at the helm.

There are more than 60 million refugees around the world, more than at the end of World War II. As a result of the Syrian war, eight million Syrians are now displaced and another four million have fled to neighboring countries. The same number of people passed through Ellis Island in the 62 years that it was open.

Despite its problems, Syria had been a functioning country, with doctors, lawyers and scientists, Mr. Shipsey said this week in a conversation with the Gazette. “These refugees who are living in camps and are internally displaced had lives, had decent lives, and are fleeing from something awful.”

“The primary responsibility rests, of course, with Europe,” which is contiguous to Syria, he added. “But the U.S. can do and should be doing an awful lot more.” The U.S. has processed about 1,500 Syrian refugees since 2011, compared to the more than 340,000 that entered Europe this year.

Most of the refugees have fled to Lebanon, Iraq, Turkey and Jordan, countries already struggling with poverty. European citizens have increasingly pressured their governments to accept more refugees, and Mr. Shipsey anticipated similar efforts in the U.S.

While Amnesty works to address issues of human rights around the world, human chains and other actions can help draw attention to the problems and solutions. In 2009, Amnesty took part in a human chain in the Dolomites to remind leaders of the Group of Eight countries to keep their promises to Africa and developing countries.

Before this summer, Mr. Shipsey had never organized a human chain. The idea for the Dolomites project came to him last year while hiking with a friend. The northern Italy mountain range was the frontline between Italy and Austria in World War I, lending additional symbolic weight to the action on Sunday. This year marks the centennial of Italy’s entrance into the war.

“They took machine guns up these sheer mountains and fought each other on the top,” Mr. Shipsey said, adding that barbed wire can still be seen in the mountains today.

Amnesty supporters from around the world will join hands around Tre Cime di Lavaredo (the three peaks of Lavaredo), which rise jaggedly from the alpine landscape. Climbers will light flares atop each peak, signalling people to link hands.

The Dolomites project started out as a show of support for human rights in general, but in response to the events in Syria became more focused on the global migrant issue. On Saturday in the Dolomites, Mr. Shipsey will screen Margaret Nagle’s 2014 film The Good Lie, about Sudanese refugees who came to the U.S. in the 1990s.

The efforts will continue this year. In December, Mr. Shipsey and others will unveil another tapestry funded by Bono, The Edge and Ms. Ono, along with musicians John Legend, Peter Gabriel and Sting, in Cape Town, South Africa, in honor of Nelson Mandela.

Amnesty has always involved itself with artists, Mr. Shipsey said, in part because so many people have been persecuted for expressing their beliefs and opinions. When human rights are restricted, he said, “it’s the artists that get it in the neck first.”

A trial lawyer by day, Mr. Shipsey founded Art for Amnesty in 2002, and now spends about half his time devoted to the program, working with artists around the world in support of human rights. In May, he produced two concerts in Mexico City to mark the opening of Amnesty’s regional hub for the Americas, part of the group’s efforts to decentralize and expand in the global south.

U2 has been instrumental to Amnesty’s efforts over the last 30 years, drawing attention to campaigns at its concerts and funding Art for Amnesty projects. A John Lennon tribute album in support of Amnesty’s campaign to save Darfur and featuring various artists, including U2, has netted about $5 million since 2007. The Ellis Island tapestry was a thank you to Ms. Ono for giving Amnesty the right to record cover versions of Mr. Lennon’s songs.

Quoting Eleanor Roosevelt, who oversaw the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the 1940s, Mr. Shipsey stressed the importance of people taking action “in small places, close to home.” Human chains are one example of individuals coming together to form a larger whole, he said.

“It’s obviously important what happens in Congress or in the parliaments around the world. But really it matters what people do where they are.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »