Under a clear October sky this week, David Thompson stood on a concrete bridge looking out over a river of brown water that surged below.

The director of the Edgartown Wastewater Treatment Facility sees the bacteria-enriched wastewater at his plant as a massive life form. “We call it the elephant,” he said. “So we have to take our 18,000-pound elephant and make sure it has food, it has proper pH, and has oxygen. It’s a big living thing, is what it is.”

Down below, the river flowed through massive horseshoe-shaped channels where aerobic bacteria converted ammonia to nitrate, before returning to large basins on the other side of the bridge, where anaerobic bacteria converted nitrate into nitrogen gas.

For now, at least, the elephant has room to grow — and plenty of food. The plant was permitted in 1995 to handle 750,000 gallons of wastewater per day. It now receives wastewater from about 1,100 buildings, treating anywhere from 100,000 gallons per day in February to more than 500,000 gallons per day in August.

At the end of the process, condensed solids ooze from suspended tubes into large containers, to be trucked off-Island and incinerated. The clear effluent is zapped with UV light to sterilize the bacteria. It then reenters the aquifer, eventually making its way into Edgartown Great Pond.

If it weren’t for the treatment facility, the pond would likely be in worse shape, Mr. Thompson said. Like all the major estuaries on the Island, it suffers from an overload of nitrogen, coming mostly from state-regulated Title 5 septic systems that were designed to remove bacteria but not nitrogen.

Too much nitrogen can result in algal blooms that choke out eelgrass and other pond organisms, as they have throughout the region. On Cape Cod, widespread development has led to fish kills and the disappearance of eelgrass, a key indicator species. Vineyard ponds are healthy by comparison, but nearly all have exceeded their sustainable nitrogen loads, as defined by the Martha’s Vineyard Commission and the Massachusetts Estuaries Project.

Edgartown Great Pond was among the first to be studied by the MEP, a collaboration between the Department of Environmental Protection and the University of Massachusetts. The project has set nitrogen reduction goals for most coastal ponds in the state. After getting its own numbers, Edgartown agreed in 2006 to allocate 200,000 gallons per day of plant capacity to the Great Pond watershed to meet the nitrogen limit. So far, it has sewered about 200 houses in the watershed, with a goal of 300 new connections.

The Edgartown plant removes up to 97 per cent of the nitrogen in wastewater, far more than even the most advanced denitrifying septic systems, which remove about 50 per cent most of the time. Title 5 systems happen to remove about 20 per cent, but not by design.

Sewering in high-density areas near a plant may be the most cost effective way to mitigate nitrogen loading on the Island. But the high cost of expanding plant capacity has highlighted the need for alternative solutions. Many of those solutions are still in development, though, and given the amount of nitrogen still entering the ponds, some towns may have no choice but to expand their sewer capacity in the coming years.

Larger lots and lower density make sewering less feasible up-Island, although the Martha’s Vineyard Airport in West Tisbury and tribal housing in Aquinnah both have their own satellite facilities.

Each of the three centralized plants down-Island — in Edgartown, Oak Bluffs and Tisbury — uses different technology, but the chemistry is essentially the same. While the loads vary from day to day and throughout the year, the output at each plant averages about three milligrams of nitrogen per liter.

Sewering may seem like an obvious solution to the problem, but not everyone is eager to spend the $15 million or more required to extend sewer lines and increase a plant’s capacity. Oak Bluffs selectman and wastewater commissioner Gail Barmakian roughly estimated that expanding the capacity in Oak Bluffs could cost around $5 million, in addition to the cost of laying new pipes (around $10 million) and installing pump stations (around $500,000). Engineering studies alone can cost $1 million, she said.

A report by the engineering group Wright-Pierce in 2010 provided another angle, estimating that new sewer lines on the Island could cost between $40,000 and $90,000 per property, depending on their distance from the plant. By comparison, a single denitrifying septic system might cost around $30,000.

But sewers within about 20,000 feet of the plant would cost less to maintain per year than advanced septic systems. And the cost per pound of nitrogen removed would be significantly less, even for connections far from the plant. Most of the lots within the Edgartown Great Pond watershed are well within 20,000 feet of the plant.

“It’s definitely the most cost effective,” Mr. Thompson said of the sewering option. “You get rid of a lot more nitrogen for your dollar.” But he also believes aquaculture, fertilizer regulations, pond dredging and other techniques should be part of the solution.

In some cases, a mix of solutions could lower the cost of sewering by reducing the number of buildings that would need to hook up. Some towns are now looking into permeable reactive barriers, or trenches filled with organic material that can remove nitrogen by a chemical process similar to the one at work in denitrifying septic systems. “There is no one solution,” Ms. Barmakian said in an email to the Gazette, arguing that permeable barriers could be equally as affordable and effective. Besides the cost, she said, sewering could lead to uncontrolled growth, higher density and increased runoff. It also does nothing to remove the nitrogen currently in the ponds. For that, towns are exploring aquaculture and artificial floating wetlands, which are known to attenuate nitrogen.

None of the treatment facilities here were built with nitrogen mitigation in mind. The Edgartown plant was aimed at saving Edgartown harbor from pollution in the 1970s, and to promote business in the downtown area (which it did). The Oak Bluffs and Tisbury plants were mainly a response to public health concerns.

But Tisbury had also opted for a smaller plant to begin with, as did Oak Bluffs, as a way to discourage growth. “They didn’t really anticipate the need that we have now for the health of the ponds,” said Tisbury selectman and wastewater commissioner Melinda Loberg. But she also noted the difficulty of planning beyond 15 or 20 years.

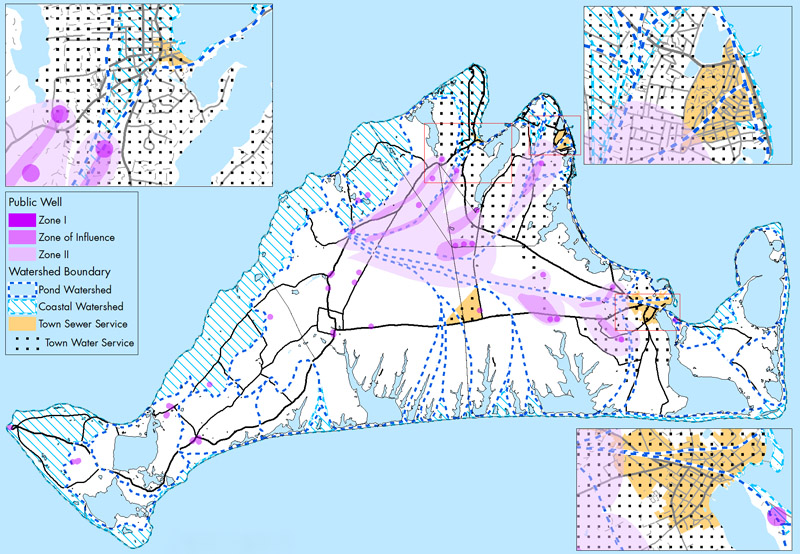

Towns often develop building regulations to go along with sewering, as a way of maintaining current growth rates in those areas. On the Vineyard, that could mean a limit on the number of bedrooms in new developments in nitrogen-reduction areas, or areas near town wells.

Mr. Thompson said the bedroom regulations in Edgartown have helped level out the rate of development. But he noted that new houses are still popping up in the watershed, and tend toward their maximum allowable size.

“This is a cliche in wastewater: If you build it they will come. If you don’t build it they will come anyway,” Mr. Thompson said. He noted the situation on the Cape, where communities have resisted sewering but development has continued at the expense of coastal ponds.

Sewers on the Vineyard are starting to serve a different purpose than they did 20 years ago. All three down-Island towns have now allocated most of their remaining treatment capacity to coastal pond watersheds, with the goal of replacing the existing Title 5 systems.

In April, Tisbury voted to expand the town sewer lines to the State Road business district, which lies within the Tashmoo Pond watershed. Doing so will not only lighten the load on the pond, but would level out plant usage, which drops sharply in the off-season. It could also allow for more business expansion by increasing compliance with Martha’s Vineyard Commission regulations.

Oak Bluffs and Tisbury have recently added new filtration beds to handle more effluent, but sewering more buildings and meeting the nitrogen thresholds will require greater treatment capacity as well. The DEP requires plants using more than 80 per cent of their capacity to be in the process of planning for expansion.

Most of the Island’s 15 major watersheds cross at least one town line, so meeting the nitrogen goals will likely require cooperation on multiple fronts. Edgartown and Oak Bluffs share Sengekontacket Pond, for example, while Oak Bluffs and Tisbury share the Lagoon Pond, whose watershed extends into four towns.

Oak Bluffs and Tisbury have formed the Island’s first joint watershed planning committee, aimed partly at allocating the costs and responsibilities for expanded sewering around the Lagoon.

“It’s really a puzzle,” Ms. Barmakian said of the allocation process. The cost of laying the main pipes, for example, would likely fall to the towns, while the cost of the connector pipes might fall to individual users. Winding roads with hills could cost more to sewer than straight, flat ones.

The Wright Pierce report argues that current septic loads should drive the allocation among towns. It also suggests that if one town had enough capacity, it could handle all the new connections in the watershed, and the other town could simply pay its fair share. But that’s not likely to happen in Oak Bluffs or Tisbury, Mrs. Loberg said, since both plants are nearing their capacity.

Each town could also handle its own nitrogen without working with other towns in the watershed, but that might not be the best approach either, because sharing capacity and resources could lower the overall cost of sewering.

“Most consultants tell us that if we do something together it’s probably going to be more cost effective,” Mrs. Loberg said.

Mr. Thompson believed that Edgartown and Oak Bluffs should form their own joint committee to explore the issue of sewering around Sengekontacket. But for now, he said, that option appears to be off the table.

“The town just spent a bunch of money building a library,” Mr. Thompson said, referring to the $11 million project just down the road from the sewer plant. “They obviously want to protect their excellent bond rating, and that means not going into any more major debt anytime soon. So it’s not being discussed.”

Ms. Barmakian declined to comment on whether the public would support expanded sewering in Oak Bluffs and Tisbury. “I would rather answer that question when people know how much it will cost,” she said. She noted that some people are dead set against it because of the potential consequences. Others believe it is the only solution. She said understanding the cost of sewering will be critical as Island towns begin to develop nitrogen mitigation plans.

“They are going to look at the money,” she said. “If it costs $10 million, maybe they will go for it. But if you are looking at $20 million and they have to share the cost . . . it may be a different story.”

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »