In an effort to protect water quality in Lagoon Pond, the Martha’s Vineyard Commission is racing to apply for a major federal grant to fund the installation of permeable reactive barriers, a nitrogen removal strategy never before used on the Vineyard.

The Environmental Protection Agency plans to award about $7 million dollars this year for coastal watershed restoration in southeastern New England, with grants ranging from around $250,000 to $1 million. It is the first opportunity of its kind under the EPA’s Southeast New England Program. The deadline for initial proposals is next Friday.

On Wednesday, a joint watershed planning committee made up of Tisbury and Oak Bluffs officials met with commission director Adam Turner and Pio Lombardo, owner of Lombardo Associates in Newton, who has pioneered the use of permeable reactive barriers on the mainland.

Nearly all of the major estuaries on the Vineyard are impaired by nitrogen, a nutrient found in wastewater and fertilizers. Too much nitrogen can lead to algae blooms that choke out other species, including eelgrass and shellfish. Most of the nitrogen in Island ponds comes from septic tanks that discharge into groundwater after treatment.

In a whirlwind presentation at the Olde Stone Building in Oak Bluffs, Mr. Lombardo explained how permeable reactive barriers have been effective elsewhere and could be “a major component of a solution” on the Vineyard.

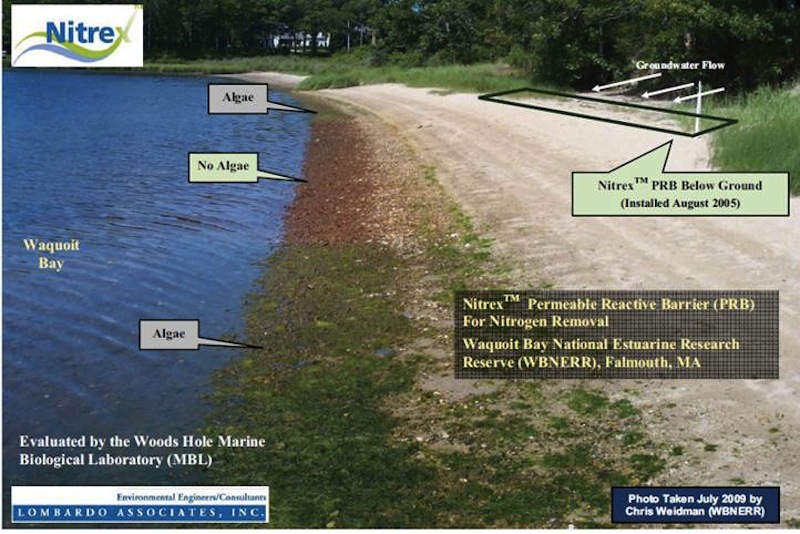

The process would involve digging shallow trenches close to the shoreline and filling them with wood chips. As groundwater moves through the barrier, nitrogen is converted to nitrogen gas through a natural process and released to the atmosphere.

A company document lists 15 permeable reactive barrier sites around the country, including two on the Cape, with nitrogen removal rates averaging around 95 per cent. “This is hardball,” Mr. Lombardo said. “We take these things pretty seriously.”

For the Vineyard, Mr. Lombardo envisioned a 700-foot barrier on the Oak Bluffs side of Lagoon Pond, one of the most impaired Vineyard estuaries, at a cost of about $600,000, including design and permitting. Committee members agreed that the Tisbury side would be too steep for the project.

The Massachusetts Estuaries Project has set a nitrogen threshold of 74 kilograms per day for the Lagoon, which would require a reduction of about 35 per cent. A feasibility study is underway to determine the best location for a barrier around the Lagoon and identify a clear reduction goal for the project.

The barriers are most cost-effective close to the shore, Mr. Lombardo said, since that is where the water table is closest to the surface. He believed a three-to-five-foot trench, covered in sand or vegetation, would be adequate for the area.

Committee members mentioned the public shoreline near Sailing Camp Park on Barnes Road as a likely candidate, but further study was needed to identify a site.

Mr. Lombardo estimated capital costs of about $9,000 per affected property, which would be cheaper than sewering, in terms of the amount of nitrogen removed. He also noted the possibility of a user charge to distribute the cost more evenly. Property lines, utilities and shoreline structures could add to the cost of installation.

The first step will be applying for grant funding. Among other things, the EPA grant program is looking for innovative approaches, especially as they relate to nutrient management and climate change. Criteria for funding also include collaboration among stakeholders, and integrating habitat restoration and water quality improvement, especially in terms of nutrient mitigation.

Mr. Lombardo pointed to the collaborative and innovative aspects of the Vineyard proposal as key advantages. But because the project was still in the planning phase, Mr. Turner emphasized the need to make a solid case. He hoped to have a draft ready by Tuesday.

“We are going to spend quite a bit of money,” said Oak Bluffs selectman and joint committee member Gail Barmakian. “But it needs to take out a significant amount.”

Comments (8)

Comments

Comment policy »