In many ways, Alfred Eisenstaedt was the most quintessential of summer visitors. The first time he laid eyes on the Gay Head Cliffs, he said, he was reduced to tears. For 50 years, he came back every August, took a cottage at the Menemsha Inn, and wandered around up-Island adding photographs of Martha’s Vineyard to a body of work that reached to the farthest corners of the world.

He took a picture of Hitler and Mussolini shaking hands in Italy, and a picture of a serpentine oak tree in West Tisbury.

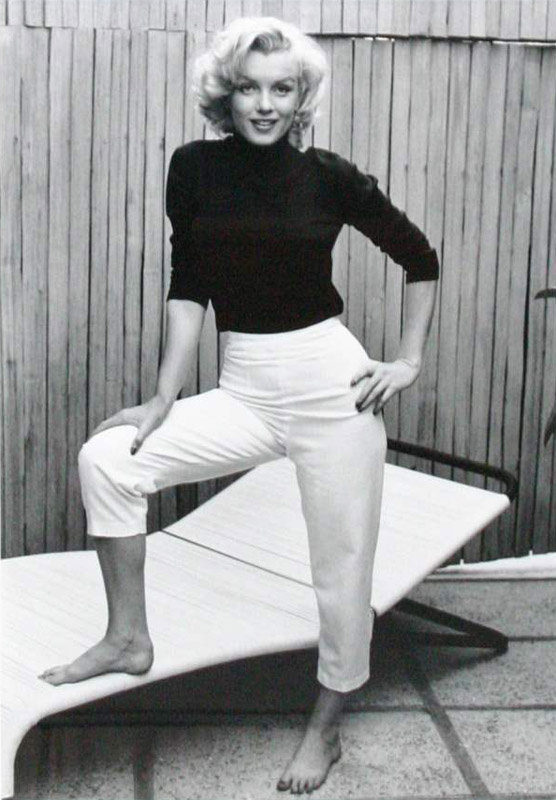

He took pictures of Marilyn Monroe at her Beverly Hills Home, and pictures of a foggy harbor in Menemsha.

He took a picture of Albert Einstein sticking out his tongue in his office at Princeton University, and a portrait of President Bill Clinton and the first family at the Granary Gallery in West Tisbury.

“He had tremendous access to the world,” said Chris Morse, who owns the Granary Gallery with his wife Sheila. “He was at the right place at the right time to chronicle world history.”

No matter where in the world his assignments for Life Magazine took him, he returned without fail to Menemsha every summer. He died here, in the place he loved, in 1995.

“He would come and hold court here,” Mr. Morse said, speaking of Mr. Eisenstaedt’s frequent trips to the gallery. “People would see him and come and sit with him.”

This Sunday, August 28, Mr. Morse will curate a retrospective of Mr. Eisenstaedt’s famous, and not-so-famous photographs at the Granary Gallery. An opening reception is scheduled for 5 to 7 p.m., and the exhibit will be on display until Sept. 11.

Mr. Eisenstaedt’s iconic photographs will hang on the same walls, and his admirers will stand in the same courtyard, as they did when the Granary Gallery hosted Mr. Eisenstaedt’s first photographic show in 1986. Mr. Morse was a teenager then, working at the gallery he would eventually own. He formed a friendship with the famous photojournalist, and began to acquire his personal collection of Eisenstaedt photographs. One of his favorites is the picture of the white oak tree.

“It’s changed a lot since he photographed it,” said Mr. Morse. “I think it’s pretty cool he made that tree famous.”

Mr. Morse said many of the photographs in the retrospective will be new to visitors. He calls them the “office prints.”

“Office prints were the images that were in boxes in his office, his travel photography, not for specific assignments, but for his own enjoyment,” Mr. Morse said.

Mr. Eisenstaedt’s photographs appeared on the cover of Life more than 90 times. His photograph of an exuberant Navy sailor kissing a nurse in Times Square to celebrate the end of World War II, is one of the most widely known photographs in history. His photograph of children watching a puppet show, in which he positioned himself under the stage, captured the wildly different reactions of 11 different children as a puppet dragon was slayed on the stage.

It made enough of an impression on Alison Shaw when she was a young photographer, that she purchased the image, though she had to squeeze her shoestring budget to do it.

“The look on their faces, so perfect, so joyful, so fearful, the moment being the most important thing,” Ms. Shaw said. “He had a real knack for capturing the iconic moments.”

Mr. Eisenstaedt shot many of his most evocative photographs in black and white, long after most magazine photography was done in color.

“Something about the black and white photojournalism sort of cuts through the riffraff and gets to the essential moment in time,” Ms. Shaw said. “There’s something so classic about it.”

Ms. Shaw said as a young artist, she was in awe of Mr. Eisenstaedt, and grateful for his support of her own budding photography career.

“I always appreciated his quiet, unspoken support of my work,” Ms. Shaw said. “We never said a lot to each other, but there was a mutual respect that to this day, means so much to me.”

Often Mr. Eisenstaedt was at the center of the social scene. He made many friends on Martha’s Vineyard, and he valued the small town feel of the Island. It was one of the things which attracted him here.

“I think it was the sense of community,” Mr. Morse said. “He liked the limelight. Maybe he didn’t seek it out, but he certainly embraced it. He was very popular.”

At a time when almost everyone has a phone camera in their pocket, and the internet pours millions of images into the steady stream of information bombarding nearly everyone, an Eisenstaedt photograph can still stop a viewer in their tracks. Yet in an interview with the Vineyard Gazette in 1987, Mr. Eisenstaedt seemed mystified about why so many of his pictures have become symbols of world history, or beloved images of the human experience captured at precisely the right moment. For him, photographing history was not a complicated process.

“I have no style. I can’t say anything about my pictures. I just can’t explain it. When I come to a place, people ask me, what are you going to do? I say, I don’t know. I have to look at the place.”

Several generations of Islanders and visitors are pleased he looked at this place.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »