Merrily Fenner had a heavy heart the day she sold her family home in Vineyard Haven. Sentimental feelings aside, she knew that it would mean evicting her six tenants, including a young couple from Brazil she has come to know over the years.

She said the sale came quickly this summer.

Because the couple does not speak English, Mrs. Fenner got on the phone with friends and reached out through social media to help them find another home. But she said the only offers were a step down in size, with monthly rents at least twice the $800 she had charged for a separate cottage on the property. The couple eventually found a temporary arrangement in Edgartown, but the future is uncertain.

“My heart absolutely broke for these kids,” said Mrs. Fenner, a lifelong Islander who has seen as many as 100 tenants come and go over the last 20 years. “One of the hardest things that I have ever had to do was to go down there and say I’ve sold the house.” She was glad at least that it happened in the fall, rather than in the spring, when the couple would have faced a much tighter rental market. “It would have been abominable,” she said. “They may not have even been able to stay on the Island.”

Housing problems run deep on Martha’s Vineyard, where low wages and a seasonal economy can create a recipe for hardship. It’s a similar story in resort communities around the country, where high-cost second homes tilt the scales of the real estate market, raising home prices across the board and creating a burden for workers and retirees.

For many Islanders, the sting is sharpest in April and May, when rents skyrocket for the summer and tenants find themselves scrambling for housing they can afford, on or off the Island. Some turn to friends, word of mouth and social media, since landlords tend to shy away from advertising to avoid the inevitable flood of inquiries that follows. With the fall may come a sigh of relief, as crowds disperse and rents return to off-season rates. But it’s not always an easy transition.

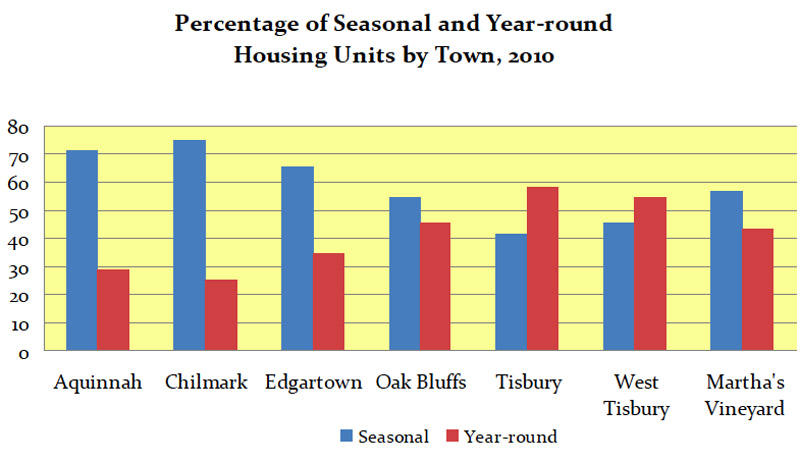

Plans to vastly increase the Island’s year-round affordable housing stock through the development of state-certified housing production plans began this year. But whether those efforts will succeed in a community largely defined by its seasonal character and high-end real estate remains to be seen.

There is evidence that a booming second-home market has worsened housing insecurity on the Vineyard in recent years. According to the American Community Survey, which provides a five-year snapshot of trends, more than 65 per cent of all new homes built since 2010 are vacant in the winter. A lack of dedicated rental developments means that most year-round rentals are in private homes, which themselves may get swept up in the housing market, as Mrs. Fenner’s was this year.

The Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University notes an uptick in construction nationwide since 2010, but a decline in rental affordability, with a record 11.4 million households paying more than half their incomes on housing. High-cost coastal communities such as the Vineyard are feeling especially squeezed.

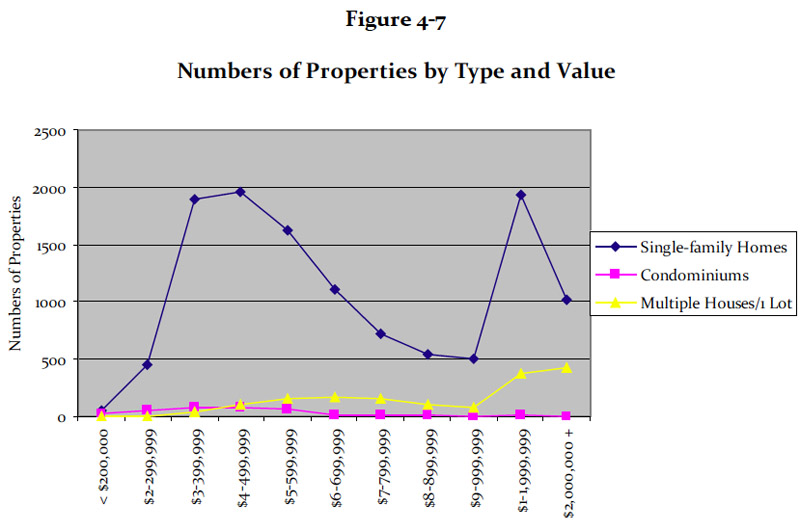

A widely accepted principle stemming from the National Housing Act of 1937 states that households should pay no more than 30 per cent of their incomes on housing. The term affordable housing also typically applies to households earning less than 80 per cent of the area median income, although different communities often set their own goals. (The median income for a family in Dukes County is about $86,000). Based on the 30 per cent rule, a two-person family earning median income would still fall about $225,000 short of being able to afford a single-family home on the Vineyard, according to a 2013 Martha’s Vineyard Commission housing needs assessment. Statewide, only Nantucket had a wider gap — around $646,000. In Barnstable County, the figure was about $31,000.

Less drastically, the average monthly rent on the Vineyard ($1,461, according to the American Community Survey) is about 30 per cent higher than on the Cape. Recent data collected for the housing production plans shows that the Vineyard has more unaffordably-housed homeowners than renters. But low wages and other factors make year-round rentals a clear priority on the Island.

According to the housing needs assessment, closing the affordability gap in all markets on the Vineyard would require annual subsidies of about $10.275 million.

The same basic factors apply to resort communities everywhere. Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket and Block Island, for example, all experience summer and fall housing migrations, known colloquially as the Island shuffle. Even thousands of miles away, a strikingly similar situation exists.

“This is the same problem all over the country,” said Scott Loomis, director of the nonprofit Mountainlands Community Housing Trust in Park City, Utah, a small resort town made famous for hosting events in the 2002 Winter Olympics. As with the Vineyard, Park City’s seasonal economy supports a thriving second-home market where many low and moderate-income households, including year-round workers, struggle for a toehold.

“If you look at the newspaper — how many homes are over six, eight, 10 million dollars, it’s just page after page after page,” Mr. Loomis said. At the same time, he added, rents have nearly doubled in recent years, leading to an exodus of year-round workers who now commute from neighboring communities. The shifting trends culminated in 2014 with an epic traffic jam during a snowstorm that left visitors and workers stranded in their cars for hours. Dubbed Carmageddon, the event finally triggered a concerted push by the town and Summit County to develop more workforce housing.

The town and county have also been working for years to boost summertime activity such as rugby and baseball tournaments to support a more year-round economy.

With more jobs will come more housing, Mr. Loomis said, and hopefully vice versa. But as on the Vineyard, the low-paying jobs typical of resort communities are a hurdle to affordability. Even with the average hourly wage climbing from around $10 to $15 in recent years, Mr. Loomis said, every employer in Park City has trouble finding workers. “It’s a problem that isn’t going to get better until wages catch up to the real estate prices,” he said.

On the Vineyard, incomes doubled between 1990 and 2010, according to the 2013 housing needs assessment, but wages were still only 71 per cent of the state average. Likewise, employment in Dukes County has expanded dramatically since 1990, but mostly in the low-paying service industry, where many jobs disappear in the winter.

John J. Ryan, an affordable housing consultant in Amherst who has issued multiple reports for the Vineyard, most recently for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission’s 2009 Island Plan, emphasized the importance of shifting resources from seasonal to year-round economic activity to support the Island community.

“The more resort-related industries you create, the more problems you have with affordable housing, because the resort-related industries don’t pay well and they’re seasonal,” he said. “If you don’t balance the economy, you are just accepting that the problem is going to be there forever.” He estimated that seasonal residents and visitors account for up to two thirds of all spending on the Island, and agreed the shift away from a seasonal economy wouldn’t be easy.

“The issue really comes down to what is the core part of the community that you’d want to make sure is there in January and February, and how do you ensure that they can do that,” he said. “What do you want the Island to look like in the wintertime?”

Along those lines, many towns on the Cape have already developed official housing production plans, which include a goal of 10 per cent affordable housing stock in each town, as outlined in state general laws. On the Vineyard, housing production plans are now underway in all six Island towns, and for the Island as a whole. A third round of public workshops this month will contribute to the final reports expected in February.

For better or worse, the struggle for housing has long been as much a part of Island life as the changing tides — characterized by periods of greater or lesser concern, depending on the national economy, demographics and other factors.

Outgoing Cape and Islands state Rep. Timothy Madden recalled taking office seven years ago in the thick of the national recession, when a stagnant economy had made affordability slightly less of a concern on the Vineyard.

“When the recession hit, all of a sudden that freed up some housing,” Mr. Madden said. “People were leaving because they had lost their jobs or they just couldn’t make a go of it and were kind of chasing after other opportunities.”

Now nearly eight years later, the pendulum has swung again. “We are back in the middle of a boom,” Mr. Madden said. “So once again we find ourselves struggling with housing. I think that is a cycle that will be endless unless we do something about it.” He continued: “It’s not just the Islands that are struggling. It’s the Cape that’s struggling. It’s actually going on in Boston and everywhere else, where there is a lack of affordable housing. How do we keep younger workers, but also people who aren’t in the upper echelon, as far as income goes?”

On Cape Cod, Heather Harper, the incoming affordable housing and community design specialist for the Cape Cod Commission, expects housing issues to take center stage as far as planning and initiatives in the next decade, beginning with a regional market study next year.

“What levers can we push as a region — from a land-use standpoint, from a regulatory standpoint or financial incentive standpoint — that might make it feasible for developers to start rebuilding that middle market?” she said. She noted a growing awareness surrounding housing issues on the Cape, but also the complexity of finding solutions in light of the region’s dependence on tourism.

“We are really recognizing that housing to support the needs of all age groups, life stages and incomes is a huge and lofty goal, and it will remain a goal,” she said.

But the goals aren’t set in stone, perhaps especially in resort communities, where much of the need extends to higher-income earners. Anne Kuszpa, director of Housing Nantucket, which targets households earning up to 150 per cent of the area median income, pointed out that the state’s 10 per cent goal for communities relates only to households earning up to 80 per cent of the median income. Especially on Nantucket, she said, where the median home price is about $1.2 million, the state goal falls well short.

Mr. Ryan called the 10 per cent goal “ludicrous” in light of the actual housing need on the Vineyard, which spans a wide range of income levels. He also pointed out that the goal does nothing to address the longstanding absence of affordable housing in the community. But he said it was a step in the right direction.

Looking back to his first comprehensive housing assessment for the Island in 2001, he cited a long-term community vision that he said targeted a range of housing needs and was unique at the time. The report also helped set the stage for widespread fundraising and a variety of housing initiatives on the Island.

“There was buy-in to the idea that this is not just a charity,” Mr. Ryan said of the public response to the report. And despite the limitations of a seasonal economy and other obstacles, he said he believes the Island is still on the right track. “This is an effort to preserve community,” he said.

First in a series examining the housing dilemma on the Vineyard.

Comments (17)

Comments

Comment policy »