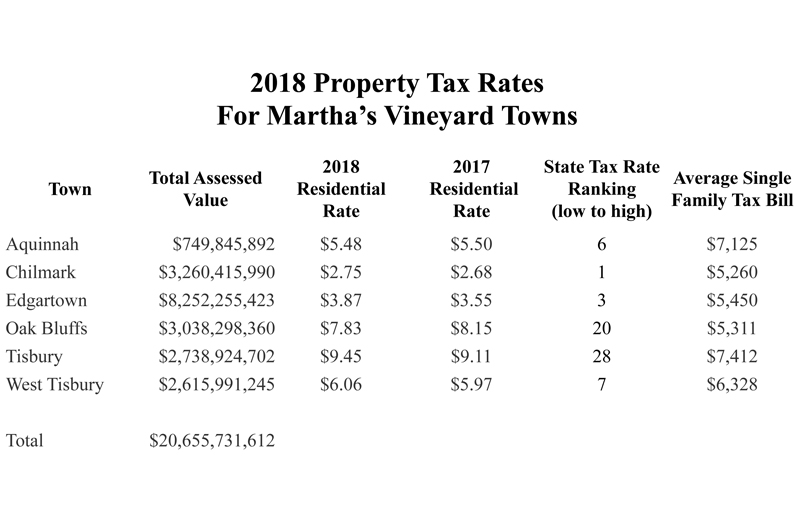

Property values increased this year on Martha’s Vineyard, topping $20 billion in total assessed value for the 100-square-mile Island, according to figures from the six towns and the Massachusetts Department of Revenue (DOR).

Assessed values were recently re-certified by the DOR, as it does every three years. The new numbers reflect rising real estate prices on the Vineyard.

Edgartown leads Island towns in total assessed value, with $8.25 billion worth of property, an increase of more than $457 million, or 5.7 per cent, over the previous year. This follows an increase of $528 million in total assessed values two years ago.

The increases make Edgartown the 17th most valuable city or town in Massachusetts in terms of residential property value, ranking close behind many of the commonwealth’s major cities and wealthiest suburbs, according to the DOR.

“Property changes at different rates in different parts of town,” said Jo-Ann Resendes, principal assessor for Edgartown. “In general in the last couple of years we have noticed increasing sale prices in the Katama area. Obviously anything waterfront tends to go up a little more than non-waterfront.”

Ms. Resendes cited numbers that show the town has long since weathered the global economic crisis of 2009, which depressed Island real estate sales.

In 2008, the total assessed value of Edgartown property was $7 billion.

For the next six years, property values wobbled but never crashed, and in 2015 they passed the 2008 mark. Values have been on the rise since then. The town tax rate increased from $3.55 per $1,000 of assessed value last year, to $3.87 this year. The tax rate for Edgartown ranks third lowest in Massachusetts.

“There were some areas that experienced very high increases, but the town also raised substantially more money than it did in the previous year, so that means rather than the tax rate goes down this time, as generally happens, in a revaluation year, it went up.” Ms. Resendes said.

The average tax bill for single family home in Edgartown is $5,450.

There are three main variables that determine tax bills: assessed valuation, town operating budgets and the tax rate.

Assessed valuation is the estimated value of a property based primarily on recent sales of similar properties. A board of assessors is responsible for evaluating how much each property is worth, and making sure each individual is assessed fairly and accurately.

The town operating budget is a spending plan for how much money the town needs to provide municipal programs and services each fiscal year. If a town plans to spend more money, in general, it will need to raise the revenue from taxpayers by raising taxes, or get the money from other sources of rev enue such as local receipts or state aid. The tax rate, expressed in dollars per $1,000 of valuation, is the multiple applied to individual property valuation to determine the tax bill. For example, if a town’s tax rate is $5, and the property is assessed at $1 million, the tax bill would be $5,000.

Other minor variables can affect tax bills, but in theory the valuation and tax rate are related inversely. If values go up, the tax rate would go down, and tax bills would stay the same from year to year, providing the towns do not raise operating expenses.

In actual practice, towns almost always increase their operating budgets each year, so the tax rate is adjusted to raise additional revenue for the towns — and taxes go up.

Chilmark has once again earned the distinction of having the lowest tax rate of the state’s 351 cities and towns, at $2.75 per $1,000 of assessed value. The rate is up from $2.68 last year.

And the Island’s second smallest town is the second most valuable town when it comes to real estate, with $3.2 billion in total assessed value, up approximately $101 million from the previous year, an increase of 3.2 per cent.

“It does seem like a big chunk,” said Chilmark assistant assessor Pamela Bunker. “New growth, our construction, equalled $32.3 million of that. It equalled $86,000 in tax dollars. New growth is definitely new revenue.”

Ms. Bunker said the value of many beach lots, which give property owners rights to privately-owned unbuilt shoreline, edged upward, helping to drive up total valuations. But she pointed to another property classification as the most significant factor in increased values.

“Any parcels that had a guest house, those sales showed those particular properties were raised 10 per cent,” said Ms. Bunker.

The average tax bill for a single family property in Chilmark is $5,260.

Densely-populated Oak Bluffs ranks third among Island towns in total assessed value at $3.03 billion. Valuations rose about $200 million this year, an increase of 7.1 per cent, the largest percentage increase of the six Island towns.

“It’s a function of the real estate market getting a little better, and there’s probably a bit more new construction than there had been in the past,” said principal assessor David Bailey. “It’s nice to see the economy moving in that direction here because we still haven’t really caught up with the individual property values at the peak of the real estate market.”

The average tax bill for a single family home in Oak Bluffs is $5,311, and the town tax rate ranks as the 20th lowest in the state at $7.83, per $1,000 of assessed value. That is down from the 2017 tax rate of $8.15.

In Tisbury, total assessed valuations came in at $2.7 billion, a relatively modest increase of about $21 million, or 0.8 per cent.

Tisbury has both the highest tax rate of Vineyard towns and the highest average tax bill for single family homes, according to the state figures.

The tax rate is $9.45 per $1,000 of valuation, up from $9.11 last year. That ranks as 28th lowest in the commonwealth.

The single family home tax bill is $7,412, when averaging both resident and non-resident bills. Tisbury is the only Island town that gives residents a discount on their property taxes.

Assistant assessor Ann Marie Cywinski said adjustments to valuations went both ways in Tisbury during the most recent re-certification.

“The big one was in West Chop, their neighborhood adjustment went up,” Ms. Cywinski said. “People aren’t really buying into the larger parcels because they cost a lot more money. Some of the neighborhoods out on Lambert’s Cove, like the Pilot Hill area, the sales showed we needed to decrease the neighborhood. It has to do with some of the properties out there that sold weren’t selling as high as the assessment that was previously assessed to it.”

West Tisbury saw assessed values rise again this year. The total for all classes of property was $2.6 billion, up approximately $84 million, an increase of 3.3 per cent. “The marketplace is showing me that prices are increasing,” said Dawn Barnes, principal assessor. She increases were distributed fairly evenly across all areas of town and all classes of property.

“No significant jumps. Pretty much the market is definitely showing an increase,” said Ms. Barnes. She noted that over the past five years, values have risen 8.6 per cent. “Most of that 8.6 per cent has been in the last two years. The end of calendar year 2015 forward we’ve seen an increase,” the assessor said.

The tax rate for West Tisbury is $6.06 per $1,000 of valuation, which ranks seventh lowest in Massachusetts. Last year’s tax rate was $5.97. The average single family tax bill is $6,328.

Aquinnah, the Island’s smallest town, has the lowest total assessed value but saw a significant increase over the previous year. Valuations total $749.8 million, up about $42 million, or 5.9 per cent.

Assistant assessor Angela Cywinski said the relatively steep rise in values left some taxpayers with questions.

“We make sure everyone is fairly assessed and they only pay their fair share,” said Ms. Cywinski. “Some people are a little shell shocked. I knew it was going to have some ripples. But it’s what the market is.”

The town tax rate went down to $5.48 from $5.50 last year, which ranks sixth lowest in the state.

The average single family home tax bill is the second highest on the Island at $7,125.

This is the final year that the DOR will re-certify property valuations on a three-year cycle. Though town assessors must still adjust valuations each year based on their own evaluation of recent property sales, the DOR will begin full re-certifications on a five-year cycle.

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »