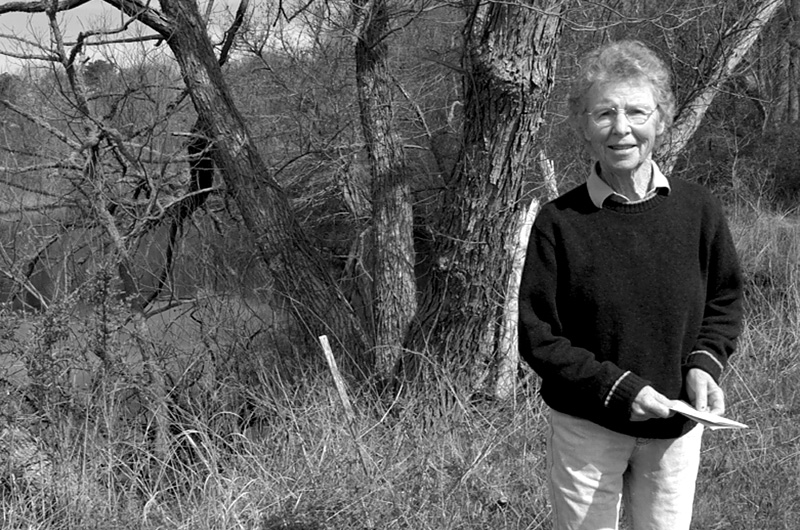

Edith W. (Edo) Potter, a longtime Chappaquiddick resident and one of the earliest leaders in conservation on the Island, died Wednesday morning at Pimpneymouse Farm on Chappy, after a long period of failing health. She was 91.

Edo Potter wore many hats, in Edgartown politics and in a wide array of areas involving conservation.

She was one of the first architects of zoning in Edgartown in the 1970s. She served as an Edgartown selectman for a dozen years, and also served on the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, the Edgartown planning board, Edgartown conservation commission and the Martha’s Vineyard land bank commission.

She was an accomplished equestrian with a love for the land forged in her earliest years at Pimpneynouse, the farm established by her father Charles Welch in 1932. She managed the large coastal farm for almost 50 years — haying, boarding horses, cutting firewood and conserving woodlands.

In a 2011 interview in the Gazette she described Chappaquiddick in the 1930s. “It was absolutely open,” she said. “There were no trees, there were sheep farms and it was just totally different, but glorious as far as we were concerned.”

In 2010 she published a memoir about her life at Pimpneymouse titled The Last Farm on Chappaquiddick.

Edith Welch was born Jan. 5, 1927, in Boston, the daughter of Charles A. Welch and Ruth Yerxa Welch. She grew up in Marblehead, graduating from the Wheeler School in 1944, then attending Vassar College for an accelerated three-year program during the war years.

She met Robert Potter while skiing as a teenager (their parents were friends). They married in 1947, and had four children. They lived in Cambridge and Concord while Bob was a college and graduate student. Edo took up dog training for obedience and field trials, taught athletics at the Shady Hill School and raised her three young daughters. In the 1950s and 1960s they lived in Princeton, N.J. and Providence, R.I. In 1970, they moved full time to the Vineyard while Bob commuted to Brown University, where he worked part time.

At the time there were about 30 people living year-round on Chappy. But Mrs. Potter quickly became involved in civic life.

Working at her kitchen table, she drafted new zoning rules for Chappaquiddick and took them to the town planning board. “Much to my surprise and delight, they accepted it,” she told the Gazette in the 2011 interview. “Then they took it to town meeting and it passed.”

Later in the same decade she played a leading role in one of the first large conservation initiatives: the preservation of hundreds of acres of open space in the Great Plains of Katama, including Katama Farm and the Katama Airfield. The property remains as open conservation land today. In 1987 Mrs. Potter received the President’s Public Service Award from The Nature Conservancy for her conservation efforts. It was one of many such awards she would receive over the years.

As a politician, Mrs. Potter was a staunch defender of the democratic process.

“I give a lot of credit to the voters. They really have had some vision,” she told the Gazette in a 1990 interview as she prepared to step down as a selectman after her fourth term.

Her quiet leadership drew widespread respect from political leaders and conservationists around the Island. But she kept her own counsel. When Sen. Edward M. Kennedy proposed the Nantucket Sound Islands Trust Bill in the early 1970s, a controversial measure that would have placed the two Islands in a national trust much like the Cape Cod National Seashore, Mrs. Potter opposed it.

“I am utterly convinced that the Islanders can protect their Island themselves if they are given the opportunity and tools,” she wrote in a letter to the Gazette in 1972.

The Martha’s Vineyard Commission eventually emerged as a compromise to the Kennedy Bill. Mrs. Potter was among the first to serve on the commission.

As a conservationist, she drew from her deep roots. “In the old days, you could go anywhere on this Island,” she told the Gazette in a 1987 interview. “People were so generous with their property and there was no feeling of threat if a stranger walked through. As kids we wandered all over Chappy and as teenagers we wandered all over the Vineyard . . . Every piece we can save means that someone in another generation can have some of the pleasures that I did.”

She was also an optimist. “People say, why bother, the Island is already ruined. But I don’t feel that way. The Vineyard isn’t what it used to be. But it’s relative. There’s always something to be saved. It’s never too late.”

Flags were lowered to half staff in Edgartown this week.

Mrs. Potter was predeceased by her husband of 70 years in 2017. She is survived by her four children: Mary S. Williamson, Katherine P. Miller, Hatsy Potter and Stephen W. Potter; and four grandchildren: Grier H. Potter, Trip G. Potter, Elliot A. Miller and Whitney A. Miller.

Funeral arrangements are pending and will be announced when available.

Comments (65)

Pages

Comments

Comment policy »