The current leader board for the Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass and Bluefish Derby includes a 29.15-pound striped bass caught from a boat and a 35.83-pound bass caught from shore. Just last year a 29-pounder caught from shore won its division. In the old days those sizes would not have had a chance of making the board.

But the disappearance of the big bass is not all bad news.

Kib Bramhall, who has fished the derby for more than half a century, remembers with some fondness but also some trepidation the days of the really big fish.

“The dangerous thing about those years was there were a lot of big fish, but very few small ones,” he said.

In hindsight, that was an early indication of the collapse of the striped bass fishery in the 1980s. The big breeding females, which can deposit as many as four million eggs each spring in the bays and tributaries of the Mid-Atlantic states which are their primary breeding grounds, didn’t reproduce in large numbers during those years. The theories for this are as abundant as there are fishermen. Warming oceans, overfishing, pollution, changing migration patterns, the absence of bait fish, and the vagaries of breeding behavior all seem to play a part.

The collapse was so pervasive that from 1985 to 1992, the derby did not allow striped bass to be weighed in. Though the relatively few fish landed for the tournament would not have had a significant effect on fish stocks, derby organizers were concerned about the negative public relations aspect of weighing in striped bass at such a precarious point in the life cycle of the fish. Over the years, federal and state regulators have tried to manage striped bass stocks, instituting length limits and landing limits on commercial and recreational catches. The restrictions evolve according to estimates of the fish population, their size and breeding success.

“We’re getting a lot of small fish in,” said veteran angler and derby committee member Cooper Gilkes. “Not a lot of big fish. They haven’t got to the point where they’ve been able to grow up. I hope they take care of them this time. This will be the third time now. If they do, it will be great.”

Mr. Bramhall has a theory for the recent rise in small bass which starts with a popular folk singer and a dirty river in New York.

“I call these little bass Pete Seeger’s fish,” he said. “The singer was instrumental in creating awareness that the Hudson was a mess and had to be cleaned up. It resulted in a very, very clean river that produces a very significant portion of the migratory bass that we’re seeing today. The species, the striped bass, is healthier today than in living memory.”

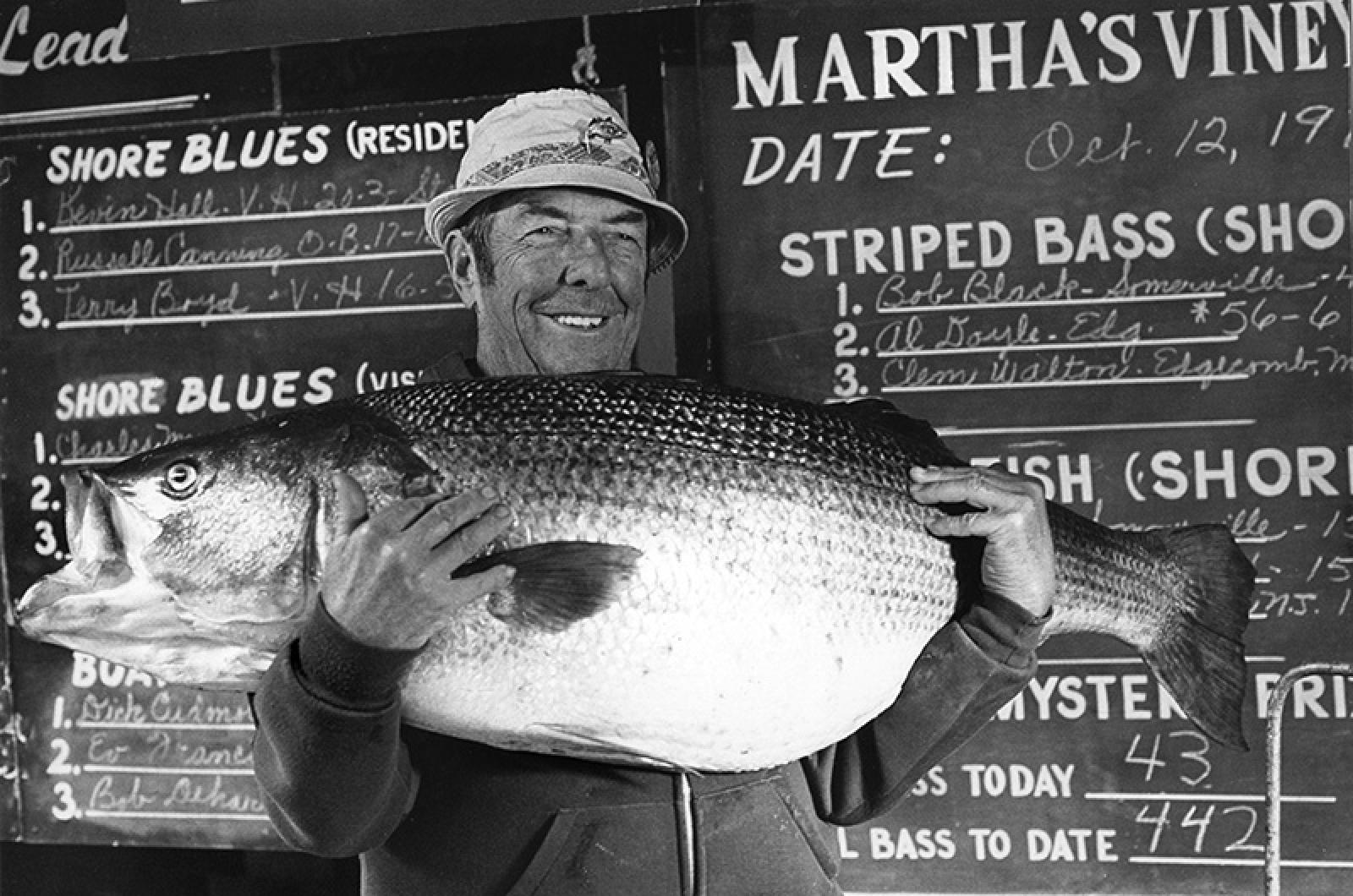

And yet the big breeding females, the ones that star in the old pictures of derby fishermen straining to hold up 60-pound bass, have yet to return. This could just be a matter of time, of waiting until they grow older and bigger, but there are other factors at work too.

Mr. Gilkes is of the opinion that overfishing of herring and spawning squid by commercial fishing boats has dramatically reduced the bait that provide a ready diet for striped bass. He also thinks it’s easier to catch them than it used to be. In other words it’s harder for the bass to reach old age.

“There’s so much pressure on these fish,” Mr. Gilkes said. “The new science, the fish finders are so sophisticated, it’s trouble for these fish if we don’t take care of them. It’s nothing to figure out where these fish live and just jack them out.”

As if there weren’t enough problems with the striped bass fishery, Mr. Gilkes said a new threat is on the increase. He said when he and his charter fishing clients are on the water now, they compete with seals for striped bass.

“Last year I had 11 fish taken off my clients and my line,” Mr. Gilkes said. “Every one of those could have been a potential winner. The seals are taking them. There are getting to be more seals every day. These seals will get trained. They’ll sit there and wait for a rod to bend and then they’re right on the fish. They’re like a dog.”

Gary Nelson, the fish biology program manager for the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, takes a scientific view of the issue. He said scientific analysis of the breeding grounds in the mid-Atlantic states showed a declining number of females entering the population in the years 2004 through 2010. That, he said, is why fewer big stripers are being caught now.

He said something happened however in 2011 that may change that trend in years to come.

“We had a huge year class in 2011,” Mr. Nelson said. “That’s the age class people are catching now. You’re getting a lot of fish 28 inches (minimum legal size by state regulation) or so. Those females in that group haven’t become mature yet. They don’t really become mature until they’re age nine or so, so we’ve still got a few years before we see that spawning stock biomass come back up. We expect those numbers to start going up as that 2011 year class start becoming older and much bigger over the next few years. We’re not too worried right now.”

Derby committee member Chris Scott is hopeful that the scientists are correct in their assessment.

“I sure hope so,” Mr. Scott said. “I remember seeing, approaching 60-pound fish, 57, 58-pound bass. They’re very impressive fish. Now 30s, 40s will win it, and there are not that many of those weighed in. I hope so. Those are the big breeding females, so obviously you don’t want to take too many of them out, but it speaks to the health of the species when you see fish that size.”

Comments (6)

Comments

Comment policy »