Vineyard Wind, which plans to build the nation’s first large-scale offshore wind farm just south of the Vineyard, is set to go before the Martha’s Vineyard Commission for a public hearing next week, offering a more detailed view of the giant renewable energy project.

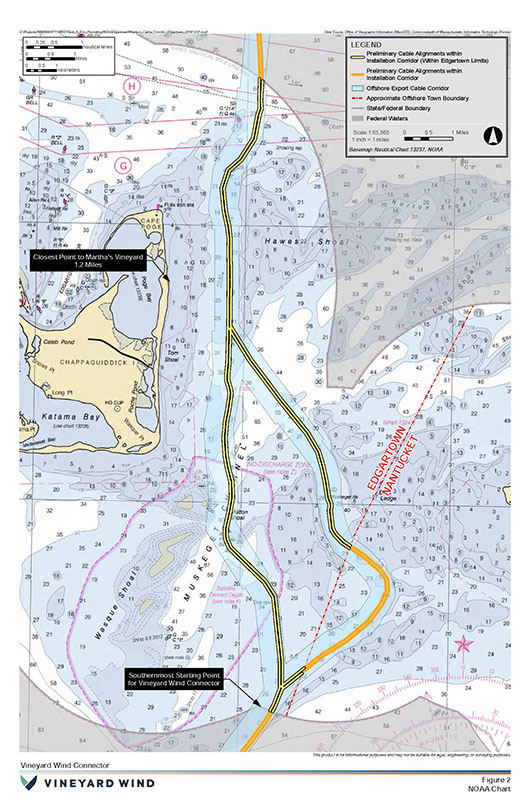

The proposed 84-turbine, 800-megawatt wind farm is expected to be built in federal waters on the outer continental shelf some 14 miles south of Wasque point. The project still needs to clear some 30 federal, tribal, state and local regulatory hurdles — among them the commission, which has jurisdiction over two underwater cables that will run from the offshore turbines through Edgartown waters. The cables will ultimately transmit electricity generated from the turbines to a switching station in Barnstable. At their closest point, the proposed cables will run approximately 1.2 miles from the Edgartown shoreline.

“We’re looking at 13 miles or so of cables in Vineyard waters,” said MVC development of regional impact coordinator Paul Foley at a recent pre-public hearing review before the commission’s land use planning committee.

The entire length of the export cables will measure between 43 and 50 miles, extending from the turbines to the point of landfall at Covell’s Beach on the Cape.

“It’s a big project,” Mr. Foley said.

The public hearing begins at 7 p.m. next Thursday, Feb. 21, at the commission office in Oak Bluffs.

Vineyard Wind is a New Bedford-based company formed from a partnership between Avangrid Renewables and the Danish company Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners. Both have been previously involved in renewable energy projects. To date the partnership has successfully acquired two leases in federal waters totaling some 200,000 acres. In the most recent acquisition in a federal auction December, Vineyard Wind was one of three successful bidders who agreed to pay $135 million for an offshore lease block.

Wind developers have six years to test conditions, develop a construction plan and clear a gauntlet of regulatory hurdles. Vineyard Wind has a partnership agreement with the Island-based energy cooperative Vineyard Power, which hopes to eventually convert the Island to 100 per cent renewable energy.

“That’s our ultimate goal,” Vineyard Power president Richard Andre told commissioners at the recent LUPC meeting.

The two 220-kV electromagnetic under sea cables would run north from the wind farm through Muskeget Channel and onto the Cape. Diagrams submitted to the commission show the cables would run parallel to the easternmost edge of Chappaquiddick, a little over one mile from shore.

Each cable will be approximately 10 inches in diameter and contain three copper or aluminum conductors arranged in a triangle shape. The metal would be encapsulated by polyethylene insulation. A cross section sample was presented at the LUPC meeting.

To install the cables, Vineyard Wind plans to use a hydro-plow or jet plow that will dig a trench approximately one metre wide in the benthic layer of the sea floor. The cable will be laid into the trench from an above-water barge, moving at approximately 150 to 200 metres per hour, burying the cable five to eight feet beneath the stable part of

the sea bed. The cables will lie about 100 feet apart. Vineyard Wind said it may have to dredge what are called “sand waves” within the cable corridor to permanently bury the cables. The cables may also need to be weighted with a concrete mattress to keep them in place in certain spots, a process called armoring.

Muskeget Channel is shallow and notoriously prone to shoaling in the strong currents that run through the area. “That area can be nasty,” commissioner Richard Toole said at the LUPC meeting. “One day you have an island, the next you don’t.”

Rachel Pachter, president of permitting affairs for Vineyard Wind, agreed.

“Muskeget Channel potentially has challenges,” she said. “We’re shifting the sand waves to the side to get to that stable part of the seabed.”

Vineyard Wind estimates the installation process for the portion of the cable running through Edgartown waters would take less than two weeks. The entire cable-laying process is expected to take a couple of months, barring inclement weather and mechanical setbacks.

Because the cables must run for some 40-odd miles, representatives from Vineyard Wind said there would have to be at least two splices along the route. If one of the splices happens to occur within Edgartown waters, the project could take longer than the estimated two weeks.

A draft environmental impact statement on the Vineyard Wind project was released in December by the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). Among other things the report describes impacts on benthic resources at the bottom of the ocean from the cable-laying work. While the report concludes there would be moderate short-term impacts from the removal and relocation of silt and sediment, it notes that the project would only affect a small sliver of the vast ocean floor.

“Despite unavoidable mortality, damage, or displacement of invertebrate organisms, the area affected by the construction footprint would be just 0.5 per cent of the wind development area [394 acres]. BOEM does not expect population-level impacts on benthic species,” the report says.

BOEM hosted a public hearing on the draft EIS Tuesday night at the Martha’s Vineyard Hebrew Center. The 500-page report details the environmental impacts of every facet of the project, from turbines to export cables to onshore facilities. While it concludes that most short-term impacts from the development are minor, including impacts on marine mammals, sea turtles, benthic habitat, tourism and recreation, it says the turbines would have moderate to major long-term impacts on some commercial fishing locations.

Public comment on the report runs until Feb. 22.

At the LUPC meeting, spokesmen for Vineyard Wind touted the company’s commitment to reducing both its own and the state’s environmental footprint. They said the route they chose from the wind farm to the Cape was sited to avoid eelgrass beds and core habitat for North Atlantic right whales. Last month the company signed an agreement with three conservation groups to protect the right whales, ensuring that construction would be curtailed when whales were in the region, that vessels would restrict their speed, and that construction crews would dampen noise to protect the communication patterns of large marine mammals.

In January, an aggregation of 100 of the critically endangered whales was spotted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration just east of Vineyard Wind’s current lease holdings.

While the draft EIS notes limited concern for the short-term impacts of the cables on sea floor habitats, more mystery surrounds the long-term effects of the cables. Ms. Pachter said the cables have a life span of more than 30 years, similar to the wind farm itself, and are required to have a decommissioning fund that will support their removal or replacement in three decades. But little is known about the potential effects of 220 kilo-volts of electricity coursing beneath the ocean floor. The BOEM report concludes that while many marine species would detect the electric and or magnetic fields emanating from the cables, the effects would ultimately be small.

“BOEM anticipates that, by burying cables and containing them in grounded metallic shielding, the impacts of EMF should be minor on finfish, invertebrates and essential fish habitat,” the report says.

“We’ve got to get ready,” Mr. Toole said at the LUPC meeting. “All of these questions are going to come up at the public hearing.”

Comments (34)

Comments

Comment policy »