Richard Darman, of McLean, Va., and Edgartown died of acute myelogenous leukemia on Jan. 25 in Washington, D.C. He was 64.

A member of President George H.W.’s Bush’s cabinet, he held senior policy positions in the federal government under five Presidents. At the time of his death, he was a partner in The Carlyle Group, a global private equity firm, was chairman of the board of AES Corp., one of the world’s largest power and alternative energy companies, and chairman of the board of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. A resident of Jacob’s Neck on the Edgartown Great Pond, Mr. Darman cherished the Vineyard and the many summers and winter weekends he spent there with his family.

He served in the Bush cabinet as director of the Office of Management and Budget from 1989 to 1993. He was the principal negotiator of the 1990 budget agreement, which produced the largest single deficit reduction program in U.S. history. The agreement was controversial when enacted because it included a tax increase. But it was later viewed as having contributed fundamentally to the return of fiscal balance in the 1990s. Enacted in the midst of a brief recession, the agreement was followed by the longest period of uninterrupted economic growth in American history.

Former President Bush called Dick Darman “a loyal friend who dedicated most of his life to public service, usually working behind the scenes in government agencies to make life better for all Americans.” Former secretary of state James A. Baker, a close friend since their days working in the Commerce Department together under President Ford called Mr. Darman “a brilliant, dedicated and distinguished public servant, educator and businessman who could direct traffic through the intersection of policy and politics as well as anybody I have ever known.”

In addition to serving in the Bush cabinet, Darman’s government service included posts in the White House and six cabinet departments. In the Reagan administration, he served as assistant to the President from 1981 to 1985, and was centrally involved in the enactment of major tax and budget agreements, as well as the Social Security compromise of 1983. He then served as the Deputy Secretary of the Treasury from 1985 to 1987.

He received treasury’s highest award, the Alexander Hamilton medal, in recognition of his contributions to historic tax reform (1986) and international economic policy coordination (the Plaza Accord of 1985 and the Louvre Accord of 1987). He served as Assistant Secretary of Commerce in the Ford administration. And in the Nixon administration, he served as an assistant to Elliot Richardson at the Departments of Health, Education, and Welfare, Defense, and Justice. He resigned with Mr. Richardson on the occasion of the Saturday Night Massacre, when President Nixon ordered the firing of his Watergate special prosecutor, Archibald Cox.

In the nonprofit sector, Mr. Darman served in several capacities. He was a trustee of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. For the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, he chaired its Blue Ribbon Commission, served as chairman of its board and led the Star Spangled Banner Campaign for the comprehensive transformation of the museum. He was long associated with Harvard University. At Harvard’s graduate school of government, he served as a member of the Overseers’ Visiting Committee from 1989 to 1998 and 2003 until his death. He was public service professor from 1998 to 2002, in which capacity he chaired the master of public policy program and received the Carballo award for outstanding teaching and distinguished public service.

He was also a member of Harvard’s overseers’ committee to visit the medical school, the committee on university resources, the committee on technology and education, the Harvard Fund Council, a director of Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and a John Harvard Fellow.

He graduated with honors from Harvard College in 1964 and from Harvard Business School in 1967. He received honorary doctoral degrees in science, business administration, and law. He was the author of technical publications in the field of public policy and commentary in such journals as Foreign Affairs, U.S. News and World Report, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and The New York Times. In 1996, he published an account of his years at the center of public economic policy making titled Who’s In Control? Polar Politics and the Sensible Center.

Born in Charlotte, N.C. on May 10, 1943 Richard Darman grew up in Woonsocket, R.I., and Wellesley Hills. He first came to the Vineyard as a teenager, visiting friends in West Chop. With its rich beauty and aura of isolation, the Island would capture his imagination for life. In 1967 he married Kathleen Emmet, a writer. Kathleen had spent nearly every summer of her life on the Island where each summer her family would gather at Chappaquonsett on the north shore in Vineyard Haven, where Kathleen’s grandmother, the late Helen Pratt Philbin, owned a collection of homes (Helen Pratt Philbin donated Philbin Beach to the town of Gay Head in 1968. Mr. Darman’s sister in law, Linsey Lee is the curator of the oral history center at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. As young graduate students in Boston, Richard and Kathleen would spend winter weekends at a family home on Lake Tashmoo. They had three children, two of whom were christened at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Edgartown. The Darmans spent every summer and many winter weekends vacationing on the Island.

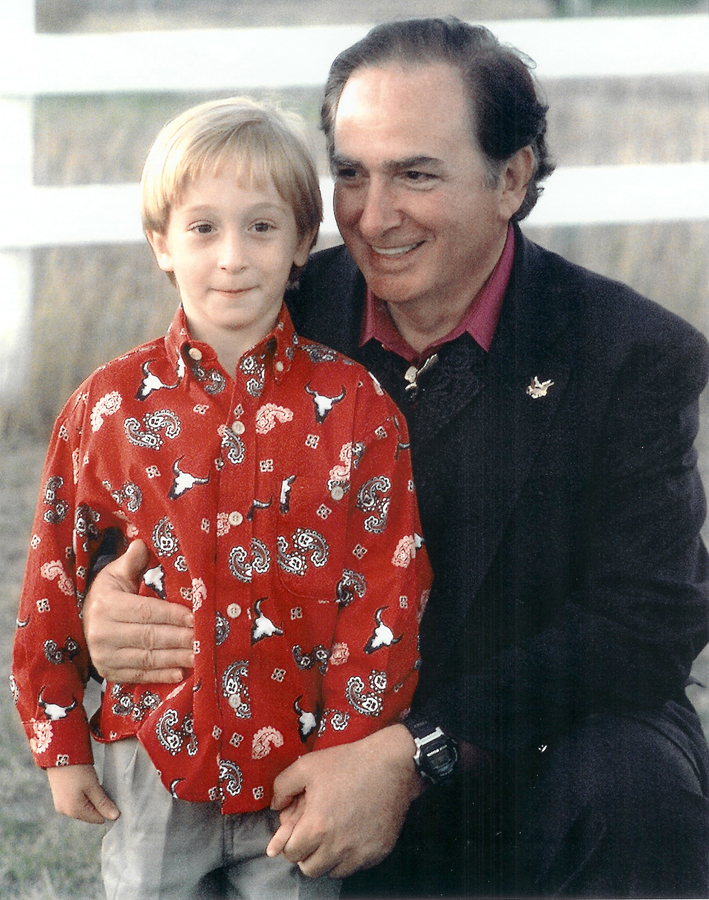

Mr. Darman loved the Vineyard for its promise of restoration and renewal. Shortly after he left government in 1993, his eldest son, Willy, suffered complications from a pituitary tumor and grew gravely ill. After a long, difficult hospitalization, Willy recovered fully and was able to spend the following Easter on the Vineyard with his family. That cold but pristine April weekend, Mr. Darman drove his family down a long dirt road to a quiet plot of land overlooking the barrier beach at Edgartown Great Pond. The landscape was new to all the Darmans, but they were home. That summer, a family that had been granted a second chance at life moved to the south shore, to a home Mr. Darman had designed himself. Its name was Easter Point.

The days Mr. Darman spent there in his final 14 years of life were among his happiest. Always drawn to service, he took a keen interest in the issues facing the Vineyard as it grew and changed over time. He worried over the effect of rapid growth on the Island’s fragile ecosystems and took a keen interest in helping to protect the Island’s natural and cultural heritage. He was a founding member of the board of directors of the Great Pond Foundation and, at the time of his death, was a member of the board of directors of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

Uncomfortable in any shirt without a collar, Mr. Darman once told a New York Times reporter that his only hobby was work. But while he was never anxious to fully unwind, in his last years on the Vineyard, Mr. Darman learned to let his imagination wander again with the boundless energy of a Harvard undergraduate in a dining hall, solving the problems of the world. Friends and family members marveled at the hidden gifts of time spent with him on the Island — how early morning coffee at Espresso Love could turn into an impromptu seminar on how to truly address global warming, how a brisk walk across the coastal plain at Thanksgiving brought promises that hope and happiness really were possible in the world. A lifelong passion was photography and on the Vineyard’s south shore, he found his great subjects: swans in the pond at dawn, children crashing in the summer surf, empty canoes in the half-light.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Darman is survived by their three sons, William of Brooklyn, N.Y., Jonathan of New York, N.Y. and Emmet of McLean, Va.; and by a granddaughter Jane. He is also survived by his mother, Eleanor Darman of Lincoln; a sister, Lynn Darman of Washington, D.C.; and a brother, John Darman of West Bridgewater. Hundreds of friends, family and former colleagues gathered for a memorial service in McLean earlier this month.

Gifts of condolence or remembrance may be made to Smithsonian National Museum of American History or the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »