Lucy (Bideau) Hart Abbot welcomed a great many people into her life. She had a tremendous capacity for giving. Her back door, covered with the decals of many organizations to which she contributed, gives a good indication of what kind of person she was: ACLU, NAACP, AMVETS, Paralyzed Vets, Wilderness Society, Madre, Physicians Without Borders, PAWS, Rosie’s Place and the Southern Poverty Law Center. She gave $5 or $10 a month to all these when she was working as a cleaning lady for $8 an hour.

She housed displaced persons after World War II; she started SPAN, a day camp for city kids in Connecticut; she volunteered her energy and spirit to many Island organizations including Martha’s Vineyard Community Services, the public schools and Meals on Wheels; she gave a room to women at risk; she babysat and read to children whose mothers needed a break. With a generous spirit and a proclivity to see the best in people, she loaned money to countless people who just needed a little help. She was the head teacher at the Pre-Start School for children with handicaps where she showed her love for each and every child.

During the turbulent sixties, she was a quiet revolutionary, befriending those who were in distress, including some members of the Black Panthers from New Haven. Her house was always filled with people who came to enjoy the good company they found in her home; Judy Collins sang on the couch; Chandler Moore popped in through a window; one of the Harlem Globetrotters stood in the kitchen talking to Margie Packish. Bideau baked pies for the Mooncusser Cafe, and several of her kids were allowed to sneak in the back door to hear the music. There were teepees on the lawn in West Tisbury and countless young people living in various rooms for a week, a month or a year. She never turned anyone away who needed a place to stay, whether a hapless teen or a homeless puppy. She lived simply, sharing what she had. She was easily pleased by a cup of coff ee and a jelly donut, or the companionship of a Mahlersymphony. She and everyone at the table read over meals. When she could, she started every day with breakfast and a book in bed.

Bideau was raised with a group of cousins who all shared a remarkable sense of humor. They lived in family enclaves in New Britain, Conn., and in Harthaven in Oak Bluffs. Their parents’ conservatism was tempered and undermined by the remarkable influence of the very liberal headmaster at the small private school which had been founded by the family. Ms. Bideau remembered that the cousins never had to knock; they could just walk into any house in the area because they were all related and always welcome. They spent as much time in the kitchen with the cooks as they did with their parents. They sailed and rode, put out an amazing newspaper, and generally had a great time. The close relationship continued to the day she died. All who knew this amazing group were envious of the closeness they had and the stories they shared.

Bideau spent her married life with her husband Frank in Connecticut but was always happiest on the Vineyard. She moved to the Island for good in 1969. She worked as a teacher, hostess, waitress, bartender and cleaning lady, all while going to school part-time. She loved fixing up places, and owned seven different houses on the Vineyard. She always loved Oak Bluffs and was a loyal denizen of the PA Club. Bideau loved music, literature and art, and every house she owned was filled with all three. She had boundless energy and liked to run at night between Harthaven and the seawall. When her heart made that impossible, she still walked everywhere. She mowed with a hand-mower and chopped wood into her eighties.

Her son Christopher remembers:

“My mother essentially adopted my wife, Diane, as another daughter when we were just kids. Mom somehow survived two concerts by the Rolling Stones in 1964 and ’65, where the screaming was louder than the music. Later, she accompanied Diane and me to the Fillmore East, where we heard many exciting musicians of the late ’60s, and where, with her dear friend Ed Clerk, she seemed to feel right at home. Eventually, she would attend concerts of the Boston Symphony at Tanglewood and Symphony Hall with us, and it was my great privilege to introduce her to Benjamin Zander, the extraordinary conductor of the Boston Philharmonic. Mom was open to all kinds of musical experiences. When my young family moved to the Island for what we thought would be a spring and a summer, she allowed us to build an apartment onto that amazing barn house on Look’s Pond in West Tisbury, home to teepees and sundry guests as well as siblings. My son Sixten grew up in this extended family, but mostly he was secure in the knowledge that Bee-Doe was always nearby for baby-sitting and to be read to — he especially liked to share Peanuts cartoons with her. Several years later, they spent nearly a year at Mom’s house in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, where Sixten was introduced to Mom’s English family, the Bradleys, many of whom attended his wedding to Shannon at the Parsonage in West Tisbury, completing a circle begun so many years earlier.”

When she was in her fifties, Ms. Bideau decided to take trips to England, a place she and her father had loved to visit. She began by taking summer courses at Oxford University and eventually bought a small house in Woodstock, a short distance away. She could walk in the grounds of Blenheim Palace, where she may well have covered the entire 2,500 acres in her perambulations; she liked to think that she could have done a better cleaning job at the Palace than the Duke of Marlborough’s regular staff.

Her grandson Sixten remembers:

“She disdained fantasy, perhaps because she was so dedicated to truth: never one to attempt to disguise mistakes, her own or those of others. Although she would almost certainly dislike being so labeled (considering that she lived mostly by defying labels), I would say that her entire nature was Zen. When she chopped wood, she chopped wood; when she cleaned, she cleaned, and nothing else. She once stunned a UK passport inspector by declaring (correctly) that she owned a house in Woodstock — yet her passport listed her occupation as housecleaner. We should each of us hope to live so honestly.”

Her grandson Jesse recalls:

“Our conversations often drifted, easily and heartily, toward two subjects: politics and religion. As to the former, we consoled each other when our nation began to look like a banana republic on another planet, something Bideau never would have cared for in a movie, let alone in her own country. With regard to spiritual matters, in my teens and twenties, I was always trying to interest her in my most recent esoteric discovery. I now realize those topics were not much more valuable than the science fiction or fantasy plots I mindfully steered clear of out of deference to her realism. Still, she was endlessly patient with me, offering a counterpoint of thoughtful openness to my youthful hardheadedness and religious certainty. I remember realizing at my last visit with her that her beliefs had migrated from a onetime skeptical agnosticism (something I was fascinated by during my childhood) to perhaps the most vividly lived form of Christianity I have seen. Some of our contemporary high-profile Christians (a mix that should be an oxymoron!) could learn volumes from the service, work, and overflowing generosity that were her spontaneous practice. Never caught up in any type of sectarian views, she was nonetheless a longtime and respected parishioner of a specific vital community: the Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association. Bideau was like a Dorothy Day without a chronicler or official entourage. But her unofficial entourage, or more accurately, the vast informal community of which she was a quiet leader, will not let her life be forgotten.”

Memories of her are bubbling up from every corner, on and off-Island.

Her daughter Genevieve remembers:

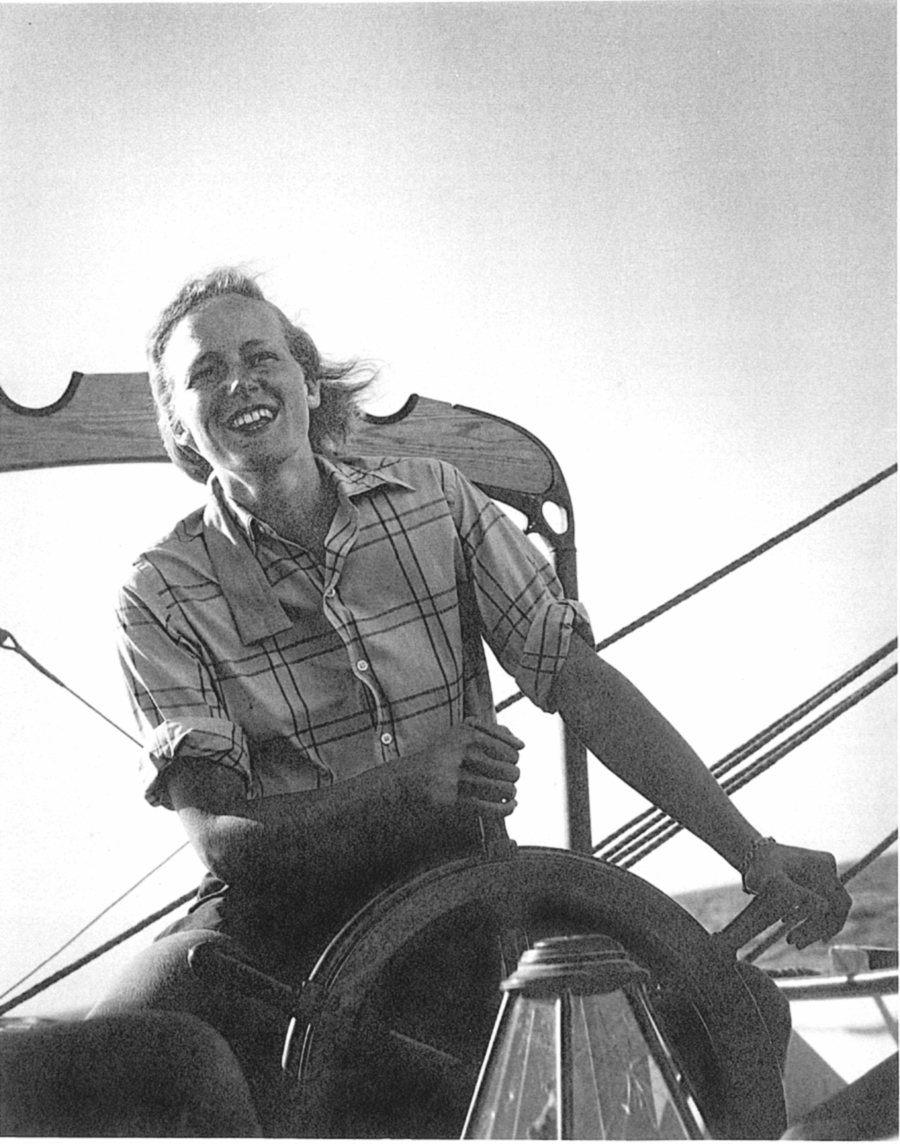

“Mom. I’d go on deck just to see her. Her mop of white hair and her weathered face, smiling. It could be cold with wind off the harbor but she never wore a hat. There she was waving as the ferry pulled into the slip. I returned home often and we grew closer as she relaxed into old age. I went to church with her, we tended her garden together. We shared a fierce love for our pets. We said — we’re so much the same.

“Mom was a real lady. Classy. And strong and independent. Loving of her children and caring of causes. Generous. Mom was bright and beautiful. She led with her heart. But she could only fight so long.”

Her grandson Seth recalls:

“She was an extraordinary woman with a rare gift for passing on knowledge, variety, decency and old Yankee values of modesty, frugality, charity, honesty and caring for the downtrodden to others, particularly her loving family who, as these testimonies show better than anything else, benefited from the intellectual fruits of her labor.”

Bideau was predeceased by her son, Kim. She is survived by her brother, Stan Hart; her four children, Lucy, Genevieve, Chris and Martha; five grandchildren, Jesse, Sixten, Crispin, Ben and Seth, and a great-granddaughter, Tasya.

If everyone who shared our house or who was the beneficiary of Bideau’s bounty were to write in, the names would fill this paper. She will be greatly missed.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »