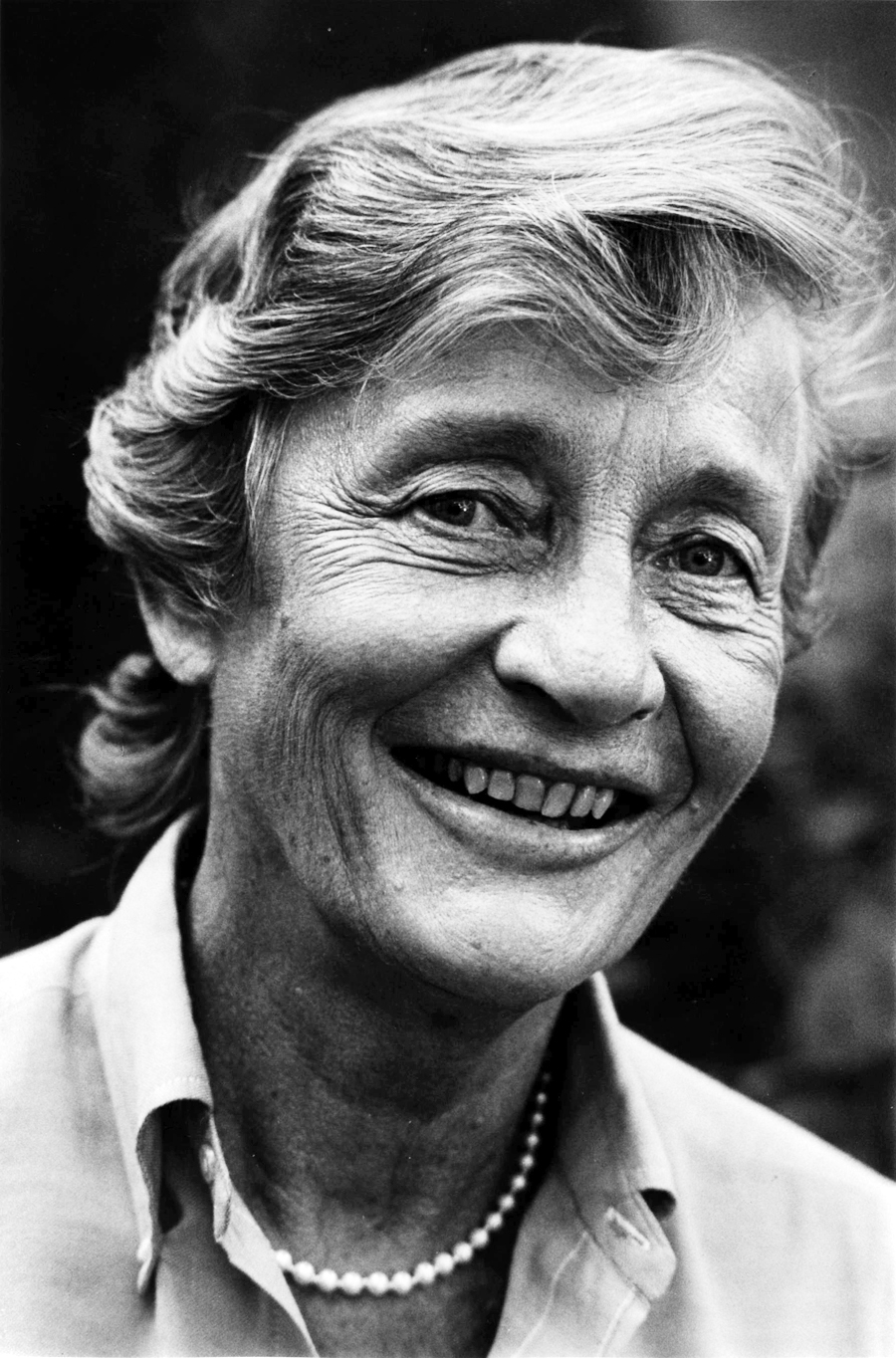

Katharine (Kay) Winthrop Tweed, a Vineyard publisher and photographer who launched the Island S.P.A.Y. program and was a friend, critic and inspiration to dozens of aspiring Island writers, and former art editor at New York’s Viking Press, died at her home in Northern Pines on Lake Tashmoo on Sunday. She was 89 and had been in failing health for some time.

She was born on Jan. 16, 1920, in New York city, a daughter of the late Harrison Tweed and Eleanor Roelker Tweed.

“There were only two Tweed families in New York in the 1920s,” she said in a profile of her that appears in the winter issue of the Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, which was on its way back from the printer at the time of her death. “One was ours and the other was Boss Tweed’s — the colorful, infamous, Tammany Hall, Democratic crook [who died in 1878] . . . we always said he was no relation . . .”

After an exotic childhood spent between Paris, France, Trieste and a woodland castle in today’s Slovakia, with summer holidays at Montauk on Long Island, as a teenager she returned full-time to the United States to attend Milton Academy, followed by studies at Sarah Lawrence College. Her schooling was interrupted by her marriage at the age of 20 to Archibald Roosevelt, grandson of President Theodore Roosevelt.

With her new husband, she moved to Spokane, Wash., and then to California, where their son, Tweed, was born. When World War II began, her husband, who had been a student of Arabic, joined the intelligence branch of the Army and was sent to the Middle East. Kay and their son followed him, first to Tehran, Iran and then to Beirut, Lebanon. Outspoken and forthright as she was, however, Kay soon found that being a diplomat’s wife was not to her taste.

It was not long before she met a Scottish psychiatrist and writer, Robert Blackwood Robertson, who would become her second husband. They moved to Scotland where they roamed the border country talking with shepherds and sherpherdesses and collaborated on a book, Of Sheep and Men. Dr. Robertson did the writing while Kay did the photography. One of the shepherdesses they met was Isabella White, who later moved to the Vineyard as a result of Kay and founded the landmark Scottish Bakehouse in Vineyard Haven.

Following a divorce from Dr. Robertson, Kay returned to New York where her experience as a photographer led her to become the art editor at Viking Press, producing coffee-table picture books. She also completed her studies at Sarah Lawrence.

In 1956, she came to the Island for a long stay with an old Sarah Lawrence classmate and New York friend, Florrie Dalton Perry, a West Chop seasonal resident. Kay had once sailed to the Vineyard as a child with her father and had never forgotten it.

Soon she was in search of a Vineyard house of her own. She found it at Northern Pines where the cartoonist Denys Wortman was selling a cottage with a view of the water.

Life on the Vineyard was vastly different from the bustling life of New York city; to make a living, she began taking pictures of children.

“She always caught the essence of the people she was photographing — particularly children,” her longtime friend Margie Vernon, the mother of some of those children, recalled. “She had a way with young people. She was able to make a young person feel important by listening to them.”

In those early Island years, Kay also did a series of portraits of Gay Head Wampanoags that now hang on the tribal center walls.

New York friends had warned her that Island life might make her stir-crazy. It didn’t, but there continued to be a certain allure to traveling, and in 1965, in a camper she named The Flying Turtle because she said its shape resembled one, she set off across the country with two Yorkshire terriers. Her assignment was to take photographs of fine homes that the owners had decorated themselves. Earlier, she had done a Viking Press book called The Finest Rooms by America’s Great Decorators.

When she returned to the Vineyard, with books and writing still on her mind, she established the Tashmoo Press to produce books about the Island by Islanders. An imaginative, indefatigable and adept editor, she encouraged neophyte writers who had good ideas. But she also published Island works by established writers. Among the 24 books that bore the imprint of the Tashmoo Press were The Scottish Bakehouse Cookbook by her friend Isabella White, Where the Birds Are by East Chopper Mabel Gillespie, Far Out the Coils by Henry Beetle Hough (done in association with the Nathan Mayhew Seminars), Edible Wild Plants of Martha’s Vineyard by Linsey Lee, and The Crimson Cage by West Chop dog officer Margaret Tuttle. A story about unwanted puppies, it became a bestseller around the world.

An animal lover from childhood, Kay and Henry Hough, editor and publisher of the Gazette and similarly devoted to animals, established the Society for the Protection of Animal Young (S.P.A.Y.) program on the Vineyard. The program provided money for pet owners who lacked the funds to have their animals spayed or neutered. West Tisbury veterinarian Michelle Gerhard-Jasny lauded the success of the program in reducing the number of unwanted animals on the Island.

“Kay was a remarkable lady,” Dr. Jasny recalled. “She’d come in to see me with her dogs and then we’d talk about other local dogs and about S.P.A.Y. And we’d talk local politics and national politics and groan together during the Bush years. And always she was in overalls with a string of pearls around her neck.”

Ever elegant, even in her bib overalls that were sometimes denim, sometimes velveteen, pearls were the only jewelry she would wear, her son Tweed remembers.

As well as being involved with the Tashmoo Press and with S.P.A.Y. during the 1960s, Kay helped out her friend and neighbor Thomas R. Goethals at the Nathan Mayhew Seminars that he had established. She assisted in fund-raising and with the design and production of the school’s catalogue. “And around 5 or 6 o’clock, if we’d had a hard day, we’d get together for martinis at her house or mine. And, of course, she’d always be in white Keds,” he recalled.

Like the pearls (sometimes real, sometimes faux), and the overalls, snowy white sneakers that she washed and bleached every night and frequently wore unlaced were part of her everyday costume. “Kay was the only really free spirit I have ever known,” said her friend Margie Vernon.

Never a cook, when she lived in Scotland, she instituted what she called a cooking regime. One night, Dr. Robertson would do the cooking, the next night, her son Tweed would be the cook. The third night, presumably Kay’s night in the kitchen, leftovers would be served. Similarly, when she lived in New York, the floor of her kitchen was so covered with photographs and papers that preparing meals in it was virtually out of the question. Nor was bookkeeping among her fortes. In the living room of her New York apartment, she kept a large birdbath on a pedestal, empty of water but filled with papers. When a guest inquired once what the birdbath was for, Kay replied cheerily, “Oh, dearie, that’s where I keep the bills.” Mary Kann of Vineyard Haven devotedly tried to keep her financial books in order since Kay’s concern was only for books within covers. Another person who helped her keep her daily affairs in order was Penny Uhlendorf of Vineyard Haven.

She disliked early rising. Once when she was visiting Arizona it was necessary for her to take a 7 a.m. flight home. Bleary-eyed Kay remarked to the driver who had arrived to take her to the airport, “Oh, dearie, so this is where the sun comes up.” Dearie was her favorite form of address to those of whom she was fond.

And she was fond of many people from all walks of life. She was known among her friends and family for her generosity of spirit, her loyalty and her knack for adopting people. Among them was Juan the Tipi Dweller, her son recalled. “He was from Venezuela. He was part Spanish, part Indian. He pitched his tipi on our land every summer for years.” Tweed’s friends were also readily adopted and at Thanksgiving time, more than two dozen would sometimes be gathered around her Northern Pines dining table.

In the same way that she was adept with the young children she photographed, she was known for her ability to empathize and understand them as they grew older. She was a devoted godmother to Fleur Perry Green, who recalled how once when she was a young adult in financial need, Kay wrote a check for her that allowed her to take a course in Tai Chi. “And it has become the center of my life. She knew how to listen to young people and to affirm their hopes and their dreams,” she said.

She was an equally devoted grandmother to her son’s two children, Amanda and Winthrop Roosevelt, who were frequent summer visitors at Northern Pines. Last summer she enthusiastically accepted an invitation from young filmmaker Victoria Campbell of Hollywood, Calif., whose grandparents and great-grandparents she had known, to play a role in her movie House of Bones about her family’s West Chop summer home.

In recent years she was not an outdoor person, but she never failed to enjoy the view of Lake Tashmoo out her study window and the birds that darted in and out of her bird feeder.

Characteristic of her sense of humor were two signs outside her house: one was a little metal sign attached to the entrance door to her cottage that read “Attention — Chien Bizarre!”; the other was a handpainted sign as you approached her home with Pooh Bear and Piglet following Christopher Robin and saying: Slow! Bears, Children and Others.”

Although she was a reader rather than a television viewer, she watched the trial of O.J. Simpson eagerly, explaining away her interest by saying she was learning about the legal system. She was also a devotee of the actor Patrick Stewart, who played Jean Luc Picard on Star Trek.

“But now I’m tired,” she concluded in the magazine interview. “Remember, dearie, I’m almost 90 years old now, and I’ve told you a very, very long story.”

Katharine Tweed is survived by her son, Tweed, of Boston and his wife Leslie, her grandchildren, Amanda and Winthrop Roosevelt, also of Boston, her nephew, Nelson Aldrich of North Stonington, R.I., and her dog Muffin, a 12-year-old bichon frise shih tzu cross.

Interment will be private at her mother’s family’s Green Farm in East Greenwich, R.I. A memorial service is being planned on the Vineyard for Memorial Day weekend in 2010.

Donations in her memory may be made to Hospice of Martha’s Vineyard, P.O. Box 2549, Oak Bluffs 02557, or to S.P.A.Y. at 318 Northern Pines Road, Vineyard Haven 02568.

Comments

Comment policy »