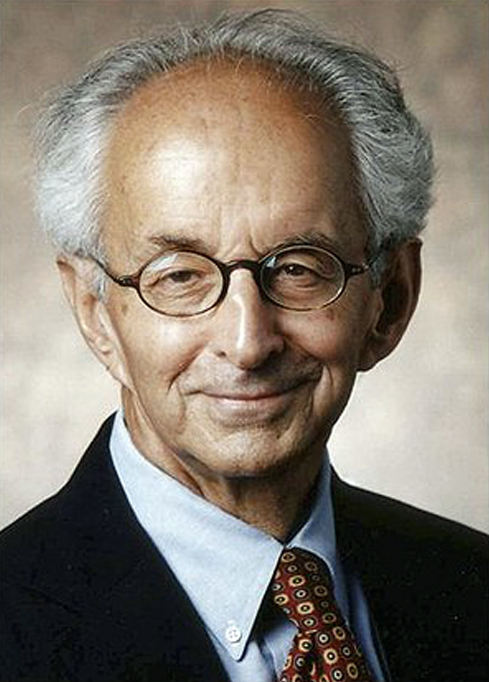

Daniel J. Freed, a Yale Law School professor who was a leading intellectual influence and commentator on how Americans convicted of crimes should be sentenced, died Jan. 17 in Manhattan of renal failure. He was 82 and lived in Guilford, Vt.

Professor Freed also had an important role in shaping the modern concept of bail. His writings, notably the 1964 book Bail in the United States — written with Patricia M. Wald, later a prominent federal appeals court judge — influenced landmark legislation in 1966 that brought what scholars described as greater fairness to federal bail practices.

But it was in sentencing, another area of the law that had drawn little attention in law schools, that Professor Freed had his most profound influence.

Kate Stith, a professor and former acting dean of the Yale Law School, said Professor Freed had devoted much of his career to “examining and exposing the parts of the criminal justice system that were, when he began his work, most opaque and basically unregulated by law: bail and sentencing.”

He pioneered the study of the subject when he brought Alabama state judges, a largely conservative lot, to Yale Law School to discuss with students what the sentences should be in hypothetical cases.

For decades, judges had unquestioned power to impose sentences using their own discretion with little fear of appeal. Mr. Freed argued for more regularity in sentencing. It was unfair, he asserted, that the same crime committed under similar circumstances could result in widely different sentences, depending on the luck of the draw of which judges presided over the cases.

His writings influenced the passage of the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, which called for a federal commission to establish sentencing guidelines. But he soon became a critic of how the remedy was used.

In practice, he said, the guidelines imposed a mechanistic rigidity on sentencing by obliging judges to adhere to a complicated set of charts and tables in determining a sentence. Deviating from the guidelines exposed a judge to reversal by a higher court.

The new process, he asserted, merely shifted discretion from judges to others in the system, notably prosecutors, who could control sentencing by choosing which criminal charges to bring. A prosecutor’s discretion in selecting charges became the primary factor in sentencing, he argued, because once a conviction was obtained, judges felt largely bound by the guidelines.

Mr. Freed was a founder of The Federal Sentencing Reporter, an influential publication that he used to chronicle sentencing developments and to argue, usually gently, that the system had gone awry. He urged judges to resist the rigid guidelines and to write opinions explicating their reasons for doing so.

Nancy Gertner, a federal trial judge in Boston and an authority on federal sentencing, said Mr. Freed had urged judges to reason among themselves and to produce a body of law that would transform the guidelines into recommendations instead of mandates.

In 2005, a divided United States Supreme Court in Booker vs. United States ruled for the first time that the guidelines were not mandatory, bringing the system more in line with what Mr. Freed had envisioned.

Dan was born in New York city and attended Yale College and Yale Law School. After serving in the Navy, he worked in the Justice Department and became director of the criminal justice division under Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.

He joined the Yale Law School faculty in 1969 and helped found its clinical program. He left his full-time post in 1994 but continued to teach for some years.

Dan first came to the Vineyard in the 1960s and summered in various Menemsha houses and introduced his family to some of the special joys of life, surfing and fishing. He subsequently bought a farm in Guilford, Vt., but continued regular visits to the Island.

He is survived by his wife, Judy; two sons, Jonathan and Peter; two daughters, Amy and Emily; two brothers, Norman in Chilmark and Harvey in San Francisco; and six grandchildren.

Comments

Comment policy »