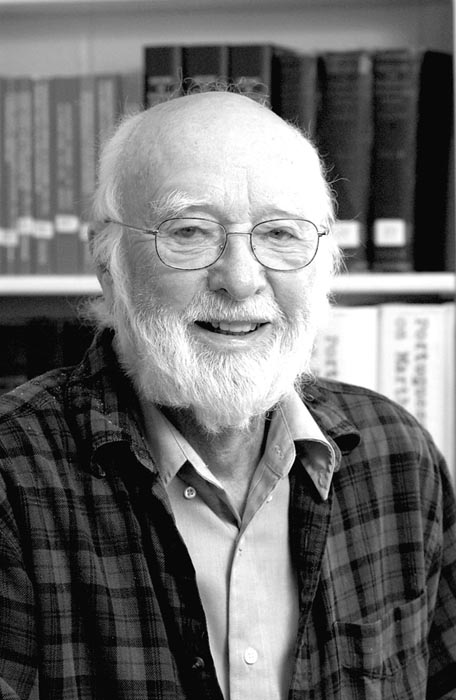

Arthur R. Railton of Edgartown and Chilmark, who wrote and published more original Vineyard history than anyone, and who crowned his career as editor of the Dukes County Intelligencer by writing the first book-length history of the Island in nearly a century when he himself was 90, died Thursday at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital in Oak Bluffs. He was 95.

In a life whose good fortune he attributed more to luck than to planning, Mr. Railton saw and appreciated the ironies in it all along the way:

He found love through war; trained to be a newspaperman but served much of his professional career in business; adored sailing but spent most of his time on Menemsha Pond running races from a committee boat; and happened upon the most satisfying work of his life at retirement, when he began to edit a quarterly journal of history for the county historical society in 1978. As editor of and a principal writer for the Intelligencer he began to uncover and report stories he found in what was in those days the irregularly and incompletely organized basement of the Dukes County Historical Society in Edgartown, today the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

Mr. Railton didn’t much like it when people called him a historian, though.

He often said that he had little interest in the big ideas of history, especially when it came to telling the tale of a small Island off the southeastern coast of Massachusetts. Instead, he thought of himself as a journalist who happened to be looking for stories that were old, hidden away and forgotten. He edited stories in the Intelligencer with the urgency of someone manning the city desk of a metropolitan paper and wrote with the punchy style (and sometimes the dark and subtle humor) of a court reporter. But as with many journalists who stay with one subject for a long time, he could not help, on occasion, but tie things together thematically and force an occasionally discomforting re-examination of received opinion and Vineyard lore.

When he accepted with great pride the Martha’s Vineyard Medal from the museum in August last year, Mr. Railton recalled how in 1977 then-Intelligencer editor E. Gale Huntington convinced him to take the job. “He was 72 years old and he said he was getting too old for the job,” Mr. Railton said. “Well, I was 68 at the time and kept the job for 30 years.”

Kay Mayhew introduced him at that ceremony. “My favorite story about him,” she said at the time, “is when the bones found in Jamestown, Va., were finally identified as those of the explorer Gosnold, some bright person called Art to tell him. His response was classic. He replied, ‘Well, we knew he was dead.’ ”

The last great irony of his life caught Mr. Railton entirely by surprise — the fame he achieved on retirement from the Intelligencer when his book, The History of Martha’s Vineyard: How We Got to Where We Are, was published to acclaim in the spring of 2006.

Buyers raked it from Island bookstores, many of them learning of Mr. Railton’s work for the first time just as his 28-year career at the museum was coming to a close. The Intelligencer, a small, softcover journal published four times a year, had gone out only to the membership of the museum, and Mr. Railton, a self-effacing man with a slight hitch in his gravelly voice, grumbled about the sudden demand to dress up, sign books and accept praise from fawning strangers. But there was a light in his eye as he complained.

And he did it all for free. Mr. Railton worked as editor of the Intelligencer as a volunteer, never asking for or accepting a dime for the 5,000 pages of history he researched, edited, wrote and published over the course of nearly three decades.

“Extraordinary. What a gift to the future,” said Matthew Stackpole, then the executive director of the museum, during an interview about Mr. Railton’s work in 2006. “And it’s a gift to this organization, obviously, but bigger than that. It’s a gift to this Island. To the people who come here for generations, his work will stand. How do you value that? How can you really communicate to people those hours [he invested]? The giving of himself? One cannot overstate what a gift — I really think that’s the word — it is to the future.”

Arthur Roy Railton, known to his family as Roy but to all his friends as Art, was born Sept. 23, 1915, in Regina, Saskatchewan. He was the first child of Albert and Anne Railton, who had emigrated to Canada from Yorkshire, England, the day after their marriage two years before.

Albert Railton worked on a wheat ranch outside Regina before going to Europe with the Canadian army in 1917. Young Art’s mother had a sister living in New England, and she moved there with her son. Art’s father returned from the war and went to work in a mill in Lawrence. The Railtons settled in Salem, N.H. Albert and Anne Railton had four daughters after Art.

Mr. Railton was the first member of his family to go beyond high school. He worked his way through college in two stints, finally graduating from the school of journalism at the University of Iowa in 1939, at the age of 24. Finding no work in newspapers as the Depression lingered, he returned to the mill where he had labored for a time as a boy under his father, who was still there when Art came back as a college graduate.

“Well, I had given up — no question — on this dream every young guy has,” he said in interviews with the Martha’s Vineyard Magazine in 2006. “You know, I didn’t have any money . . . and then there was nothing. I was back where I started.”

In March 1941, Mr. Railton was called up in the first peacetime draft. He joined the Army Air Force and became a master sergeant. Though he enjoyed meeting and working with men from all over the country, he still felt as if his life had no great purpose. But in the spring of 1942, while stationed at what was then Camp Devens, he received a letter from Marjorie Marks, a girlfriend with whom he’d broken up after college.

Marjorie and her mother were coming east to take a drive through New England. Would Art and his own mother accompany them? Art took leave and made the trip. “And the whole notion was rekindled,” he said of his relationship with Marge. “I felt, ‘Boy, if she came all this way, maybe I didn’t feel so bottomed out.’” He went to Officer Candidate School and married Marge right after graduation.

Mr. Railton went to Europe with the 112th Anti-Aircraft Group of the Third Army and rose to the rank of major upon his discharge. He served for the duration of the war and on April 4 or 5, 1945, found himself standing, almost literally, at a gateway to hell: The Third Army had happened upon Ohrdruf, a forced-labor subcamp of Buchenwald, abandoned frantically by the Germans only days before.

It was the second hastily abandoned concentration camp Mr. Railton had seen as the Third Army advanced on Berlin. Nothing had prepared Mr. Railton for the starving, dazed prisoners he saw at the first camp. At Ohrdruf, which Gen. George S. Patton was scheduled to visit later that day, Mr. Railton found still worse – mass killings and burials that had been abandoned while in progress. “To see this total denial of the human spirit was just shocking to me,” Mr. Railton said.

More than anything else he ever experienced or saw, Ohrdruf confirmed for Mr. Railton how much fate — his own word was luck — plays either a severe or benevolent role in life. Together with what he had seen and felt during the Depression, his experience at the Ohrdruf inspired him to keep a sharp eye out for the disadvantaged and to champion their causes.

“When I came home from the war,” he said, “I was a different person of some kind, I think, and my interests were broader and my sympathies were wider. That’s why I say the planet should have a war every generation without anybody shooting. Just to get people mixed up with each other.”

After he returned home, he and his wife, also educated in journalism, worked as reporters for several newspapers in the Midwest. But soon Mrs. Railton gave up her profession to raise their children. Over time, Mr. Railton took jobs as automotive editor at Popular Mechanics and as an executive in the communications office of Volkswagen of America, whose Beetle was just beginning to capture a share of the marketplace. At the end of his career, he wrote a popular history of the Beetle, which was translated into German and published on the 50th anniversary of the Bug.

Mr. Railton first got to know the Vineyard in 1923. An aunt had married Everett C. Fisher, an Edgartown shellfisherman, and Art, still living in Salem, began to visit Jane and Evvie Fisher for part of each summer.

Art walked over village streets paved white with scallop shells, visited the blacksmith shop of Orin Norton, the boatbuilding shed of Manuel Swartz Roberts on Dock street and watched the building of the Edgartown Yacht Club rise on the timbers of the wharf from which whaling ships had sailed 70 years before. He visited Island relatives in Menemsha and said that he always felt an odd sense of dislocation as a boy, feeling at once related to the oldest Vineyard families, but not really belonging because he was just a summer kid.

In adulthood, through his sister Dorothy Fisher, he met E. Gale Huntington, an Island historian, writer, teacher and musician from Chilmark. With their children, the Railtons, then living in Chicago, drove to the Vineyard each summer and rented a drafty camp on Quitsa Pond belonging to the Huntingtons. The children raced on Menemsha Pond and the family acquainted itself with up-Island life.

On retirement from Volkswagen in 1977, the Railtons moved to Edgartown, though they moved to the Huntington camp in summer when their children and grandchildren came to visit. In 1977, Mr. Huntington retired as the volunteer editor of the Dukes County Intelligencer, which he had founded in 1959. In 1978 he asked his friend Art to take over for a year until a permanent editor could be found.

“So I agreed,” Mr. Railton said, “and I didn’t have the slightest idea what the hell I was going to put in it.” In those days the museum was a sleepy, insular place. Mr. Railton knew next to nothing about the society. He walked over to the campus and introduced himself, assuming “I was going to come in and people were going to hand me stuff and I was going to edit it. I mean, it didn’t occur to me that it was a blank slate that I was inheriting!” he said.

He began to open dusty old boxes in the museum basement, searching for undiscovered stories. He found diaries, whaling logs, letters, deeds and ledgers from which the fine sand of blotted ink fell when he turned the pages. He realized he was seeing things that no one had looked at since the writer had closed the covers for the last time a century or two before.

The Intelligencer, which under Mr. Huntington’s editorship had traded most comfortably in first-hand reminiscences, kept doing so. But Mr. Railton saw that there were large gaps in the published record of Island history. So the Intelligencer also began to cover the past — whether personal, familial, sociological, civic or by event — almost as if it were breaking news or a special report.

The Intelligencer came to serve as an alternate — often primary – index to the vast (and in those days often uncatalogued, even unexcavated) collection of museum documents whose origins go back nearly to the time of the original white settlements in New England. It published stories on conflicts among classes and races, the rise and consequences of tourism, jealousies and disputes between towns and the marginalization of the Wampanoags. Mr. Railton once again resisted the opportunity to see larger meanings in his work: “I got hooked on this stuff. I enjoyed it,” he said, leaning back in the chair in his small basement office as the day of his retirement approached.

He had agreed to stay a year but found enough primary history to interest him for the next 28 years. He would run the Intelligencer longer than any other job he ever held.

Mr. Railton also wrote two columns for the Vineyard Gazette. For many summers, he chronicled the sailboat races held each week on Menemsha Pond. From his vantage point on the committee boat, he saw and described the often heartrending existential dramas that played out when winds shifted or died, giving grandchildren in one boat unexpected advantages over seething grandfathers in another, and allowing an esteemed professor to wallop a captain of industry — at least on corrected time.

He also wrote an op-ed column called Just a Thought, in which he often used history to show how life had changed — or remained the same — on the Vineyard. In both columns, the elemental, subject-verb-object Railton style — at once warm and journalistically skeptical, personal and yet bashfully removed from the action — was as clearly evident as it was in all his work for the Intelligencer.

He served for a time as president of the historical society, but the administrative work and the obligation to be the public face of it irked him. “I got them to pass a bylaw in their second annual meeting saying that no officer could serve more than two terms of three years. I got out of it, fortunately,” he said.

He served as an officer of the Chilmark Community Center and was an early member of the American Veterans Committee, a liberal group that formed after the end of World War II and has since disbanded.

After the death of his wife in 2000, Mr. Railton embarked on the last great work of his life. He had run serials in the Intelligencer — notably a five-part series called The Indians and the English on Martha’s Vineyard, published between 1990 and 1993 — and now, trying to fill the emptiness that Marjorie’s death had left in his life, he began to tell the story of the Vineyard from the time of the retreat of the glaciers to the start of World War II, when he believed that Vineyard history began all over again.

In 11 installments published between 2002 and 2005, the story came together in the same ad hoc, discursive, late-breaking way he had written, edited and published all his previous work. As the series evolved, Commonwealth Editions of Beverly agreed with the museum to publish the collection as a book. The History of Martha’s Vineyard: How We Got to Where We Are, came out in May 2006, the first comprehensive history of the Island to appear since the three-volume History of Martha’s Vineyard, written by Dr. Charles Edward Banks and published originally in 1911.

“Since I came here,” he said in his office as the publication date of the book neared, “I never have ever thought that I was doing the community a favor. I always that the community was doing me a favor by letting me be here. I’ve learned so much, and I’ve learned things about human character and other things that you never learn working for a living someplace.”

Mr. Railton is survived by his sons, Stephen of Charlottesville, Va.; Peter of Ann Arbor, Mich.; Mark of Hingham; and a daughter Janet of Olathe, Kan.; and by eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. He is also survived by his sisters; Elsie Rushton of Salem, N.H.; Nancy Jones of South Dennis; and Dorothy Fisher Dickie of Milford, N.H. Another sister, Ruth Gordon of Edgartown, died in 2010

His funeral service is pending for next week. Information will be published in the Gazette as it becomes available.

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »