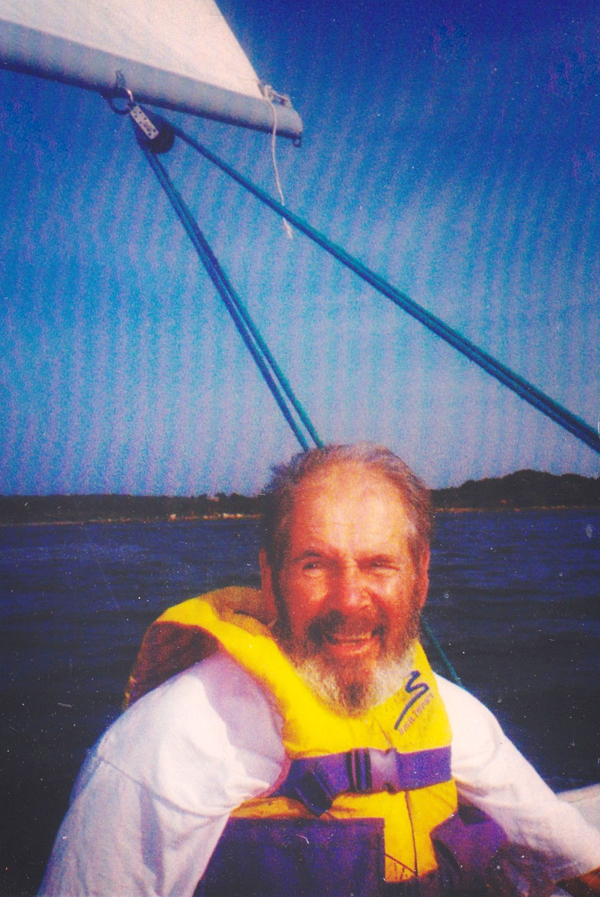

Dr. Edwin Salzman died on Oct. 3 at the age of 82.

Fifty years ago he set foot on the shores of the Vineyard and never looked back. He learned to sail from reading over the winter, and ordered an Ian Proctor 16-foot centerboard racing boat he saw in his subscription to Yachting Magazine. Self-taught, he joined a group of beached sailboats at Herring Creek on Menemsha Pond, and was told “there was a second race.” He asked for the course, and completely book-taught, won the race. After that, nothing would do but to buy land in Chilmark to store Second Wind. Over the years and with consecutive boats, he was a familiar figure on the pond, even bringing home the coveted Marjorie Dangerfield Cup.

Dr. Salzman had careers as a pioneering vascular and thoracic surgeon, medical researcher, Harvard professor and deputy editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. His research demonstrating that aspirin reduced venous thrombosis is a key reason why Americans take daily aspirin tablets.

He was born in St. Louis, Mo., in 1928 to Sophie Brook Salzman and Dr. J. Marvin Salzman, an obstetrician and general practice physician. He spent his childhood in Springfield, Ill., but attended high school living with his mother’s family in Mobile, Ala., while his father was overseas in the medical corps throughout World War II. He attended Washington University in St. Louis for college and medical school, finishing first in his class at both.

He then moved to Boston to pursue a residency in surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, where Edward Churchill, chief of surgery, was instrumental in moving the practice of surgery onto firm scientific ground.

After his internship year in 1954, he married the former Nancy Lurie and spent two years at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, in the research group developing the G-suit. The work included frequent, eye-blackening rides in a large centrifuge to simulate the G-forces a fighter pilot endures.

He returned to MGH in 1956 to train as a general surgeon. Although Jewish doctors are commonplace today, the 1950s were a different era, and Dr. Salzman would become one of the MGH’s first Jewish chief residents in surgery and only its second Jewish attending surgeon ever in its 243-year history.

He spent 1958 and 1959 working with R.G. Macfarlane at the Radcliffe Clinic in Oxford, England, investigating how blood clots, a scientific question that would animate the rest of his career and grow into a field challenging tens of thousands of researchers. He joined the MGH staff and Harvard Medical School faculty where he taught for 35 years. In 1965, he moved from MGH as chief of vascular surgery to Harvard’s Beth Israel Hospital of Surgery at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston.

In collaboration with William Harris, an orthopedist, he developed surgical techniques and the heparinized, anti-coagulating surfaces that made hip transplants survivable and practical.

His laboratory established that von Willebrandt’s disease, a clotting disorder, was caused by platelets malfunctioning. He also showed that molecules of cyclic AMP and ions of calcium within the platelet cell play key roles in telling platelets when to make clots. His most significant finding may have been the demonstration of aspirin’s antithrombotic effect in venous disease and that aspirin could prevent post-operative venous thrombosis.

He retired from practicing surgery at the age of 47, in 1976, after learning he had Parkinson’s Disease. As someone who had wanted all his life to be a surgeon, this seemed to be a devastating end. But it launched the second half of his career.

After several years dedicated to medical research full-time in his laboratory, he also joined the New England Journal of Medicine half-time as the deputy editor. Over the next 12 years, he worked with the journal’s editors and authors to keep the weekly publication at the forefront of medical research. His 1994 editorial, Living With Parkinson’s Disease, describing the personal challenges from chronic illness, received a world-wide response from physician-readers and has been incorporated into medical school curricula. His adaptation to the increasing vicissitudes of the disease turned him into a positive role model for victims and their families.

He continued to run an active laboratory and collaborate with Edward Merrill at MIT on artificial surfaces with specialized anti-thrombotic properties. These materials are now widely used in coronary stents and other implanted medical devices.

During his research career, he wrote hundreds of articles in medical journals and co-authored a standard text on hemostasis and thrombosis. He chaired the Thrombosis Council of the American Heart Association, served as president of the New England Society for Vascular Surgery and participated in several learned national and international societies. Among his honors, he received the American Heart Association’s Distinguished Achievement Award and Washington University Medical School’s Alumni Achievement Award.

A worldwide traveler and avid sailor, he spent his summers with his boats and family in Chilmark.

He is survived by his wife of 56 years, Nancy Lurie Salzman, three sailing-instructor sons — Andrew (and wife Betty), David (and wife Beth) and Jim (and wife Lisa) — and seven grandchildren, all of whom are also sailors.

Comments

Comment policy »