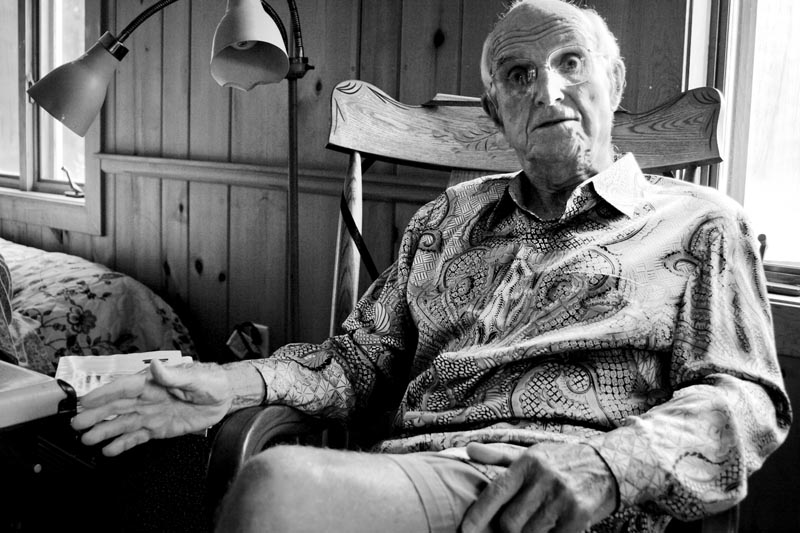

Dr. Joseph E. Murray of Wellesley and Chappaquiddick, a plastic surgeon whose pioneering work in organ transplant surgery in the 1950s later led to a Nobel Prize in medicine, died on Nov. 26 in Boston from complications following a stroke. He was 93. Dr. Murray died at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the same hospital where he performed his first kidney transplant in 1954.

“The privilege of taking care of fellow human beings is tremendous,” he told the Gazette in a 2001 interview.

He was a longtime summer resident of Chappy, a place he loved and came for quiet, simple refreshment for some 50 years with his extended family.

Dr. Murray was considered one of the preeminent surgeons of the 20th century. His career was shaped by a series of chance encounters, beginning during World War II when his surgical residency at Peter Brent Brigham Hospital in Boston was interrupted and he joined the Army. A random assignment sent him to the Valley Forge General Hospital, a plastic and reconstructive surgical hospital in Pennsylvania. One of Dr. Murray’s patients was a young aviator named Charles Woods, a precocious pilot who had been flying the so-called Hump from Burma into China for the U.S. Army Air Corps. Charles Woods was an instructor pilot, and his plane had caught fire when one of his students made a fatal error during takeoff.

“His face had been erased by fire,” Dr. Murray wrote in a 2001 book about his work and his life titled Surgery of the Soul. “Charles Woods was a human form — one whose age could not possibly be determined from his appearance. In fact he was 22 years old. What awaited him over the next two years was 24 operations, many conducted with only minimal anesthesia, and unimaginable pain. A team of surgeons was going to try to buy him a new face and functioning hands and to give him back his life.

“At age 25 I was the most junior member of the team. The questions raised and lessons learned in trying to help Charles would determine the course of the rest of my professional life.”

Skin grafting and reconstructive surgery were not new procedures, but his own introduction to this area of medicine began to stir a new curiosity in the young surgeon.

“I began to wonder whether it would ever be feasible to go beyond skin. Would it someday be possible to remove a healthy internal organ from a recently deceased person and transplant it into a person who would otherwise die?” he wrote.

The biggest problem with transplant work was immune rejection. In 1954, after Dr. Murray had been discharged from the Army and returned to Boston to resume his residency at the Brigham, he opened a private practice in plastic surgery and joined a renal transplant research team.

After many failures, his breakthrough came with identical twin brothers, Richard and Ronald Herrick. Richard Herrick was admitted to the hospital with a life-threatening kidney disease. His brother, Ronald, donated a healthy kidney and the transplant worked. Richard died seven years later after his disease recurred, but the transplant was nevertheless considered a success. Dr. Murray and his team went on to perform more successful kidney transplants among twins, and the work later moved to transplants from cadavers after they also pioneered the development of immunosuppressive drugs.

In 1990 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. He shared the prize with Dr. E. Donnall Thomas, a pioneer in bone marrow transplant work. Dr. Thomas died in October.

Dr. Murray was born in Milford on April 1, 1919. He attended the College of the Holy Cross and Harvard Medical School. While in medical school he met Virginia (Bobby) Link, a singer and musician he met at a Boston Symphony Orchestra concert. They were married in 1945 and had six children.

He devoted most of his career to reconstructive plastic surgery. He also had a deeply spiritual and humanistic side which he said was a critical component of his work. “I can remember some of my fellow medical school students, they were bright as hell and they would stand up in front of the room and ask the most erudite questions. But some of these people fell by the wayside because they could not take the responsibility of patient care and making decisions. It happens,” he told the Gazette in the 2001 interview.

His love affair with the Vineyard began in 1958, when he was deeply involved in the kidney transplant work. It was a difficult period and many of the patients had died. It was mid-summer and Dr. Murray was exhausted. His chief surgeon insisted that he take some time off. He and Bobby put the kids in the car and drove until they got to Woods Hole. “I thought it would be a fun adventure to hop on whatever boat happened along and have faith that it would take us somewhere wonderful. It did,” he recalled in his book.

They went to Edgartown, discovered Chappaquiddick and met Chappy resident Vance Packard, who was trying to move a refrigerator into his house. They helped him with the fridge and struck a deal to rent the house for a month. “I think we sensed on some level that Martha’s Vineyard would come to be deeply important in all of our lives,” he wrote.

In 1970 the Murrays bought a piece of inland property on Chappy. For two years they camped on the land with their children in the summer, hanging pots and pans from the trees, pounding their own well by hand with the help of the late Foster Silva. In 1972 they learned that the old Parmenter property was for sale at Cape Pogue. They bought 40 acres and an old Coast Guard shack, and it was their castle. Many years later they built a house on the inland property, and began to spend every summer there while the children used the camp at Cape Pogue.

Dr. Murray was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Medicine. He was also a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, which advises the Vatican on science issues. He donated his share of the $703,000 Nobel Prize to the Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Boston Children’s Hospital.

In 1986 he suffered a stroke, three months before he was due to retire. He recovered fully, but found himself a changed person from the experience. “I had long been aware that roadblocks along life’s path can become stepping stones. . . I had no regrets,” he wrote in the book.

In addition to his wife, Dr. Murray is survived by three sons: J. Link, Richard and Thomas Murray; three daughters, Virginia, Margaret Murray Dupont and Dr. Katherine Murray Leisure; and 18 grandchildren.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »