An esoteric case that has implications for the future of small parks in Oak Bluffs and throughout the commonwealth was argued at the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court on Monday.

A decision is expected sometime in the next three months.

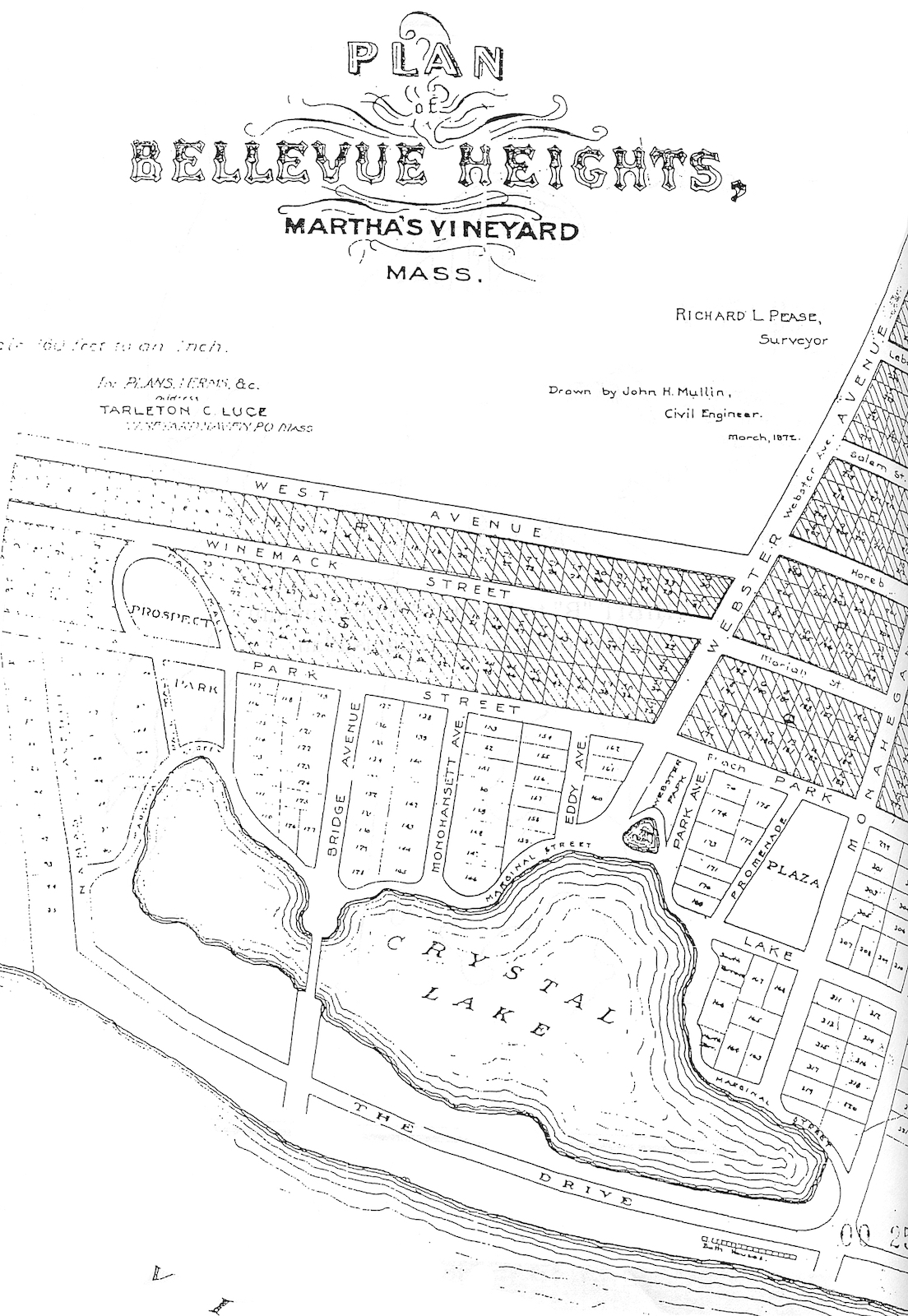

On its surface the case is about three small wooded lots behind Crystal Lake on East Chop, and whether the current owners can build there, though the lots have been labeled as parks since they were set out in an original 1872 subdivision.

The lots are by most accounts unremarkable; each one is smaller than an acre. But the legal battle is symbolic of larger conservation efforts, and the outcome of the case could decide the fate of more than a hundred small parks in Oak Bluffs that are privately owned but used by the public.

The question that the state's highest court must now decide is what developers intended when they set out small pieces of land as parks more than 100 years ago.

Attorney Daniel Perry of New Bedford, who represents a group of neighbors that are trying to block construction, argued in a brief to the court that if the neighbors do not prevail, it will mark the first time that any park in Oak Bluffs is opened to development. He said it would also be the first decision in Massachusetts that failed to protect a parcel designated as park on a subdivision plan.

"[It would be] a deeply troubling precedent that may be unsettling to the status of numerous parcels historically dedicated to open space throughout the commonwealth, especially in seaside communities," wrote Mr. Perry, who also serves as Gosnold town counsel.

Attorney Kenneth Kimmell of Boston, who represents the owners of the lots, argued that if two lower court decisions are not upheld, it will mark the first time that a court has imposed restrictions on a property based solely on a century-old subdivision plan.

Since the case first began more than five years ago, the Massachusetts Land Court and the Massachusetts Court of Appeals have both ruled in favor of the landowners - finding that the neighbors did not meet the burden of proof establishing rights to use the lots as parklands.

A wider public interest, with implications that reach beyond the three small lots in question, was underscored when the supreme court agreed to hear the case this winter.

And in fact this week was not the first time that the state's highest court heard arguments about an Oak Bluffs park.

The landmark 1891 Abbott case - decided by a state Supreme Judicial Court that included future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. - saved Ocean Park from development. Many at the time thought it saved the rest of the Oak Bluffs parks as well, none of which have since been developed.

Parks played an integral role in the creation of Oak Bluffs - dating back to the founding of the Methodist Camp Meeting Association in the mid-19th century.

In 1866 a group of investors formed a company and bought roughly 75 acres near the Camp Ground to develop a residential neighborhood for summer visitors. The company hired Boston landscape designer Robert Morris Copeland - today memorialized in the town's Copeland District - to design the community.

Mr. Copeland's plan - titled Oak Bluffs and covering what is today known as the Ocean Park neighborhood - laid out small residential lots, curved avenues and larger parcels spread throughout the community and labeled as parks. In his brief to the court, Mr. Perry noted that the inclusion of parks, which later became a common feature in planned subdivisions, was unprecedented at the time.

Mr. Copeland's design proved popular, and was repeated in eight other subdivisions created nearby between 1866 and 1880 and marketed for sale. Together these nine subdivisions defined what was then known as Cottage City.

The properties that are now the subject of the court case were labeled as parks in what was then called the Bellevue Heights subdivision, behind Crystal Lake on East Chop, which was laid out in 1872. Between the nine subdivisions, more than 100 such parks were created.

The boom of the real estate development soon went bust, however, and many of the original investors went bankrupt.

The company that hired Mr. Copeland auctioned off its remaining parcels and sold the park lots to a group represented by George C. Abbott, who then attempted to resell the parks at a substantial gain to the town. The town in 1885 took a portion of the Ocean Park property by eminent domain, and Mr. Abbott sued for damages.

A judgment in his favor by Dukes County Superior Court was overturned by the state supreme court, and the Massachusetts Attorney General brought a separate lawsuit against Mr. Abbott to establish that the parks were parks, and not intended for private property.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the attorney general and found that the parks within the subdivision were intended for public use. The justice in the case wrote that if the developers intended to sell the designated parks as buildable lots, it would have been "inconsistent with common honesty."

Mr. Perry and his clients relied heavily on the Abbott decision in their arguments for the pending case, noting how close the Ocean Park subdivision was to Bellevue Heights in both location and time. But both lower courts found his reading of Abbott was too broad and not applicable to the present case.

With the original Bellevue Heights developer no longer alive to speak about his plans, the court now only has the original subdivision map and other remaining records to interpret his intentions.

Records entered into the court proceedings are compelling. The original 1872 subdivision plan set off hundreds of numbered residential lots - all rectangular, with 50-by-100-foot dimensions - but named three unnumbered parcels as parks that were larger, of irregular size, and bounded by a road named Park street. The lots were continuously designated as parks on recorded plans and assessors maps for more than a century.

The three small lots remained off the town's tax rolls until 1994, when for unknown reasons town assessors sent out tax bills. It appears that they may have been trying to clear title to the land, as the tax collector in 1996 began tax taking proceedings.

The current owners of the property did not know they had an interest in the property until they received a letter from the town's tax attorney in 2001 notifying them of foreclosure proceedings. The current owners live in California and Nebraska and inherited the lots through two generations from an ancestor, who purchased the parks and roads in the Bellevue Heights subdivision for a nominal fee when the developer went bankrupt only a few years after designing the community.

Once the owners learned about the properties they put them on the open market as residential lots and signed a purchase and sales agreement for one of the disputed parcels with a buyer who intended to build a home. The current owners have never paid property taxes on the lots.

The original plaintiffs in the case, John and Lisa Reagan, who own a home abutting one of the parks and tried to buy the disputed parcel when it was put on the market, filed a complaint in land court once they learned someone else intended to build there. The Reagans were later joined in their lawsuit by other landowners in the area - including Renee and Bruce Balter, Anne Gallagher, and the East Chop Association.

The earlier court decisions found that the properties in question were not used by the public in the general sense - defendants noted that the properties were densely overgrown, and did not include picnic benches or playground equipment.

But in the Abbott decision the court expressly noted that open space alone was a public asset.

"The chief element of a public park . . . is to have the land kept open," the decision found. "If in a seaside summer resort, no improvements at all are made, there will be still some benefit from having space left over for air, and for an open, unobstructed prospect."

The town has a complicated and somewhat contradictory role in the case.

The town is listed as a defendant because it is a partial owner of the properties through the tax foreclosure process, but selectmen decided last year to assist the neighbors in their effort to keep the parks open. Town counsel Ronald H. Rappaport argued in favor of the plaintiffs at the supreme court this week.

The case comes at a time when the town is trying to clear title to some of the other parks throughout town. Town meeting voters last year accepted title to both Linden Park and Winne Park in Lagoon Heights; the fate of many other parks with unclear ownership hangs in the balance.

Court documents in the case cite a history of Oak Bluffs included in a book authored by the late Gazette editor Henry Beetle Hough. Mr. Perry noted in his brief to the supreme court that Mr. Hough's reflections on the Abbott decision had "ironic prescience."

Looking back on the Abbott case in 1935, Mr. Hough wrote: "The parks have been won these many years, and time has discounted the victory.

"Generations enjoying liberties won for them in the past are slow to understand how easily the balance might have been turned in the other direction. In this instance, the public right to the parks hung by a hair for years, with able lawyers and the lower courts adding to the weight of opposition. At the end the issue turned upon that slender and intangible quality of the human mind, liberal construction, the will and the ability to look beyond small logic and adherence to technicality."

Comments

Comment policy »