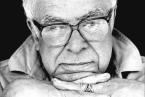

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Predictably, the conversation begins with a string of jokes and the trademark grin that starts as a tiny twinkle in the corner of the eye and then suddenly and uproariously occupies his whole face. Peals of improbable laughter spill out around the Community Hospice of Washington, where Art Buchwald has taken up residence.

But as his doctors will attest, little else about Mr. Buchwald is predictable.

Two months ago he made a conscious decision to refuse dialysis and therefore end his life. Call it a testament to the healing powers of laughter or call it a miracle, but the 80-year-old Pulitzer prize-winning humorist has defied the odds and achieved something most of us will not - the chance to reflect on his life and say goodbye. He also has gained an unexpected new celebrity status, and he is handling it all with characteristic Buchwald elan.

"I've become a landmark, I'm like the Lincoln Memorial. Someone called CNN and said Art's going to die, well let's put him on the air. But I'm still alive," he grins. Wearing a blue and white striped polo shirt, Mr. Buchwald reclines comfortably in a wheelchair in the living room of the sprawling brick hospice on this rainy Saturday morning. His illness has taken its toll on his extremities, and he has lost part of one leg. He gazes out through large windows to a courtyard draped with cherry trees just beginning to bloom, then looks around the room with a small wave of the hand.

"I get up in the morning and I come out here and it's a salon . . . the Commandant of the Marine Corps has come to visit, the French Ambassador - all of these people, it's unbelievable, and I love it. There's more laughter in here than you can imagine. I want to start charging admission for a visit - $25, I think." Then he aims a bit of incoming at the Gazette editor who has come to interview him: "I've decided that I am going to be here for as many years as Billy Graham's lawsuit continues."

Same old Art Buchwald, doesn't miss a trick.

Although he does admit to missing the Vineyard, where he has been a summer resident since 1967, where he likes to play tennis and have fun with his literary pals William Styron, Mike Wallace and Jules Feiffer, where his name has become synonymous with the Possible Dreams Auction that has raised millions of dollars for Martha's Vineyard Community Services, and where he will be buried alongside his late wife Ann in a forgotten old cemetery near West Chop.

Soon, perhaps.

Today Mr. Buchwald's thoughts are trained mostly on the Vineyard; he turns momentarily serious. "Life is very, very different on the Vineyard. It is very much about the people and the place, people walk right into your house to see you. You don't have that in Washington or anywhere else. I was at a lecture once and a woman came up to me and said, ‘I'm from the Vineyard in the summertime.' I said, ‘That's nice and maybe I'll see you there.' . . .

"Somebody told me the other day, ‘You're not going to die, we're going to see you on the Vineyard.' But we all say that to each other - See you on the Vineyard, when are you going, how long are you going to stay, I'll see you there."

The journalist whose long career as a humorist began at the International Herald Tribune when he was an expatriate living in Paris in the 1950s first visited the Vineyard in 1966 and wrote a column for his syndicate suggesting that what the Vineyard really needed was a bridge. The column drew howls of protest from died-in-the-wool Islanders near and far. Mr. Buchwald responded with a letter that was published in the Gazette. Finally it dawned on the overly serious Vineyarders that Mr. Buchwald's tongue was in his cheek.

The next year the Buchwalds rented a house in Vineyard Haven at the suggestion of his friend, Doris Kearns Goodwin; he recalls that the house was terrible, but they soon found a better one down the street. A few years later he and his wife bought their home on outer Main street in Vineyard Haven in an area that was at one time dubbed writers row, because its residents included William Styron, John Hersey and Mike Wallace. All were friends.

Mr. Buchwald has penned a number of columns over the years skewering the social hierarchy on the Island as it relates to place of residence. He remembers them all. "On the Vineyard it is important to have it right where you are from. If you are from Edgartown - well that is good," he says, drawing out the pronunciation of "Edgah-town." He continues, using his thumb as a directional guide. "Vineyard Haven?" The thumb is down. "But West Chop?" He grins, thumb up. He once wrote famously in a column that he would not go to parties in Chilmark because he refused to go to a place where you needed a map to find the house.

Not long after he began coming to the Vineyard - he cannot remember exactly when - he agreed to be the auctioneer for the Possible Dreams auction. "Harriet Sayre talked me into it, and then after I started I realized that I couldn't get out of it. I was stuck. But really it was fun and it was a way of giving back, all at once," he says.

Possible Dreams memories tumble out. There was the year the hot auction item was a private concert and a peanut butter sandwich with Carly Simon at her home, and a bidding war erupted between two men. After a good deal of egging on by Mr. Buchwald, the end result was two concerts, two peanut butter sandwiches and double the money for Community Services. Then there was the year a high-rolling woman bid up a trip for two to Vienna, but as it turned out, on that particular evening she was not with her husband, who later found out and canceled the check.

Somehow it all became part of the fun. "Even though you were on vacation, it was a way to give back, and I still had so many other things to do on the Vineyard. We played tennis . . . when I lobbed Kay Graham, she fired me from the paper," he deadpans. The late Washington Post publisher had a home in West Tisbury.

He tells another Vineyard story that if it were a film clip might star Rodney Dangerfield: "One time I met this guy who won the America's Cup in San Diego; he was having lunch at my club. I said, ‘The Vineyard Haven Yacht Club challenges you to a duel.' When I went back to Vineyard Haven I told them, ‘You need to raise $10 million dollars because we are going to have a race.'"

The twinkle fades into seriousness. "What's happened to the Island is it has become much more, obviously chi chi . . . and I think about these wonderful people who are moving because they can't pay their taxes and I think it is crazy."

There are more memories. "One time we were all at the beach and it was during the Viet Nam War and McNamara was on the Vineyard, and there we were sitting at the beach enjoying the sun and Jules Feiffer said, ‘Let's go picket McNamara's house.' I said, ‘We are having such a great time, do we have to do that now?'

"That's what it is, there is something about the Vineyard that binds us all together . . . On the Vineyard the big question is not who you are but where you've been and why you've been there. Each thing, each moment has a meaning, a place, a trail you might have walked on. The Vineyard is a very important part of my life, it's an important part of everyone's life who goes there, even when we're not there."

He says it was John Hersey who found the little private cemetery, tucked into the woods on the way to the Chop. "They were selling plots for $500 with the condition that you couldn't sell them for a profit. We called everybody, all our friends - Styron and everyone. We said you've got a place to die. John Hersey is there, my wife is there and that's where I'm going. I think I want it put on my stone: To be or not to be, this is a good question."

Jokes on hold, he reflects a bit more: "What makes it wild is, well, you know everyone dies, but when I refused to take dialysis suddenly I became a celebrity. But I don't consider myself brave or remarkable . . . the people who are on dialysis are the brave ones, braver than I am. But I've become a story."

More incoming. "In fact so much so that the Vineyard Gazette would pay someone to come down and I've never known the Vineyard Gazette to spend that kind of money."

He is still writing these days, dictating columns to his secretary from his hospice bed.

How does he want to be remembered on the Island?

"I've had such a good relationship with the Vineyard that I am not worried about how people are going to remember me, I think it will be good. The tough thing will be to find someone to do the auction there, but," he grins, "where I am going, I don't think I care."

He shows off a memento from the Island that friends brought him: a small jar filled with sand and sea glass. "The sand is from Owen Park," he beams. "It's all about how we are connected, and so many of us are connected to the Vineyard."

Mr. Buchwald sends his best to all his Vineyard friends, says to look for him there soon.

And he has a special message for his friend Bridget Tobin at the Steamship Authority, whom he raves about: "Tell Bridget if they kick me out of here, I would like a ferry ticket."

Comments

Comment policy »