Funny Business: The Legendary Life and Political Satire of Art Buchwald, by Michael Hill, Random House 2022, $28, 336 pgs.

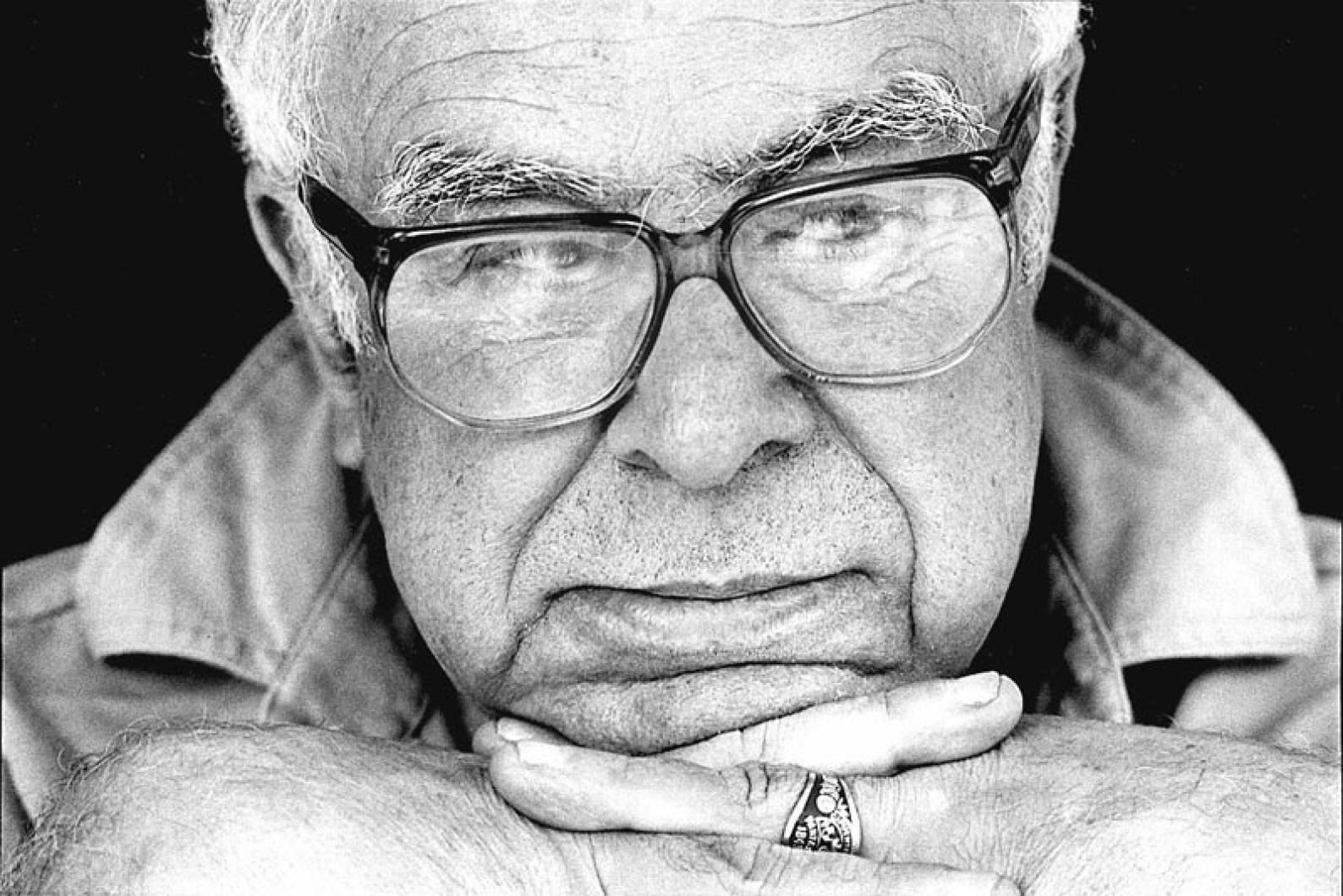

As Michael Hill hints in his sparkling new book Funny Business: The Legendary Life and Political Satire of Art Buchwald, one of the most remarkable things about long-time Washington humorist (and longtime Vineyard visitor) Art Buchwald is that he was ever able to have a career at all. Novelist Christopher Buckley points out in his foreword to the book that Washington isn’t exactly known for its carefree camaraderie. Back-knifing and grudge-holding are the most popular hobbies of the long-time denizens of the place; in retrospect, it seems impossible that a satirist could be read with affection and side-splitting laughter by members of all political tribes alike.

But three times a week, Buchwald did the impossible – and made it look easy. His Washington Post columns typically seized on some detail or moment of the politics of the day and then stretched it almost out of shape with absurd humor and gentle satire. Every week, stark enemies on both sides of the aisle would come together to chuckle over the exquisite nonsense they’d read that morning in Buchwald’s latest column.

To put it mildly, the column was a hit. It won Buchwald a Pulitzer Prize, and as Mr. Hill writes, at its peak it was read in 100 countries all over the world in 550 newspapers. The collections Mr. Buchwald assembled into books every year sold in the hundreds of thousands. He was a much sought-after speaker at events of all kinds. He was chummy with the Kennedy family. The man Mr. Hill describes as “columnist, playwright, pundit, lecturer, political commentator, wise guy, prankster, father, husband, and friend” was every bit as much a literary star as any of the novelists who were his fans (P. G. Wodehouse, for instance) or friends (the novelist Irwin Shaw, who writes to Buchwald about the creative agony of producing his future bestseller, Rich Man, Poor Man).

Mr. Buchwald’s vast trove of papers and personal effects was opened to Mr. Hill by his son and daughter-in-law (Mr. Hill dedicates his book to the couple), and it allows him to paint what will certainly be the fullest picture of this figure that will ever be made. In very short order, readers feel they’re coming to know both the humorist (a breezy perfectionist) and the man – chatty and unstintingly generous. It’s a remarkably warm rendition, something Mr. Buchwald himself would have had a great deal of fun teasing.

Despite this wealth of raw material, it’s still something of a miracle that this book ever topped 100 pages. Every morning for over 30 years, Buchwald read the morning papers in bed, got himself into a taxi (he never learned how to drive), went to his office, wrote his column, ran it by his long-time secretary, polished it up, filed it with the Washington Post and his syndication service, got some lunch, chatted with some of his colleagues, answered some mail, then went back home for supper and chatting on the phone until bedtime. Throw in a speech here or an emcee gig there, and that’s about the whole of it. It’s not exactly the Battle of Borodino.

As might be expected when dealing with such a funny, genial subject, Mr. Hill has written a funny, genial book. But even so, there’s a bit of darkness around the edges. In the 1990s, for instance, Mr. Buchwald began to tell interviewers about his struggles with depression. He and William Styron and Mike Wallace gave a series of talks on their experiences of periods of depression (they dubbed themselves “the Blues Brothers”), and Mr. Hill’s treatment is appropriately sensitive. His subject very intentionally presented a jovial face to the world, and he kept it up for so many decades that people assumed it was entirely natural — but Mr. Hill expertly shows how that facade sometimes came at a sharp cost.

He also describes in generous detail Mr. Buchwald’s often contentious relations with Hollywood, including “the lawsuit that wouldn’t die” with Paramount over Mr. Buchwald’s claim that the studio stole his film treatment for the Eddie Murphy movie Coming to America. Mr. Buchwald won the case and received many hearty congratulations from his friends for getting a cash settlement out of “those Hollywood bastards.”

But even so, this is a happy, cheerful book. Given how suffused it is with Mr. Buchwald’s humor, it could scarcely be otherwise. Its most melancholy is resolutely offstage, although I’d bet most of the book’s readers will be thinking about it. The Washington — indeed, the United States — in 2022 is so savagely polarized that things are much closer to civil war than civil discourse. It is not a leap to wonder if Washington D.C. would have any use today for the razzing laughter of Art Buchwald, even though we need him now more than ever.

Comments

Comment policy »