One of Menemsha’s most respected fishermen, Jonathan Mayhew, has quit fishing the high seas.

Mr. Mayhew recently sold his federal permits, giving up his license to ply the offshore waters of Georges Bank for cod, flounder and other fish.

A Vineyard native who grew up in a family of generations of fishermen, Mr. Mayhew, 56, said a chapter has closed in his life. He said he worries now for the future of young local fishermen facing current fishing rules.

The changes that have come down are killing the fisherman and not necessarily saving fish, he said.

“It is death by a thousand cuts,” Mr. Mayhew said.

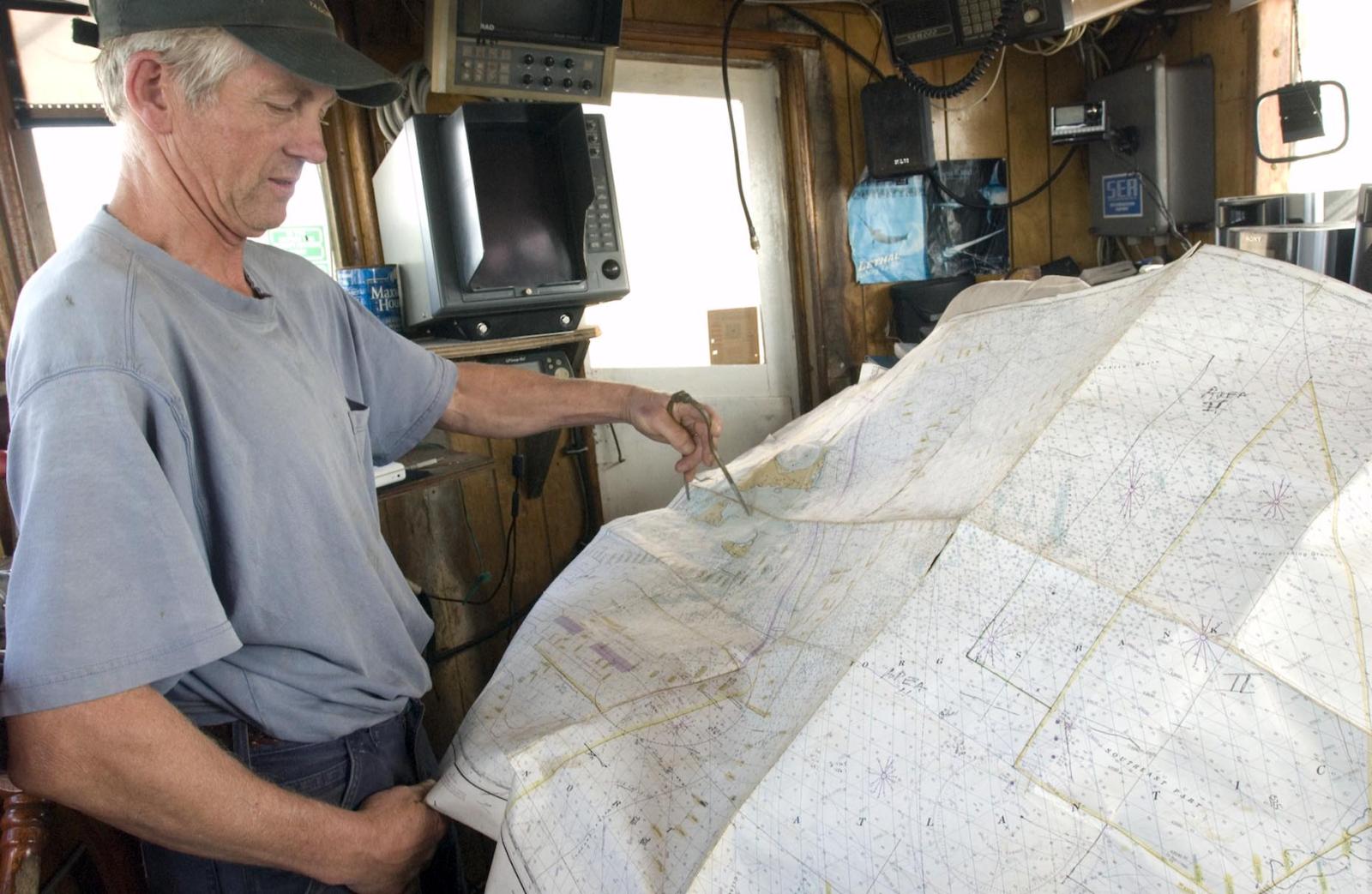

Seated in the pilot house chair of his 72-foot fishing vessel Quitsa Strider II, Mr. Mayhew talked about his decision to sell his northeast federal fishery permit.

For more than a year, Mr. Mayhew said, he has tried to sell his 30-year-old steel dragger, a boat now stained in rust and wear.

He bought the boat in 1990. So much of his career as a fisherman has been based on the idea that the next tow, the next trip will make things right.

If there is an equivalent, Mr. Mayhew’s sale of his fishing permits is like the farmer selling his land, or a truck driver turning in his driver’s license.

While Mr. Mayhew can still fish state inshore waters for squid and fluke in the spring, there is very little else he can do in those waters with a boat of the Quitsa Strider’s size.

“I blame it all on 30 years of mismanagement,” Mr. Mayhew said of the declining fisheries.

When Mr. Mayhew was younger, he and his brother Gregory fished the waters of Georges Bank and south of Martha’s Vineyard with few restrictions. They would look out for each other. The seas were plentiful with cod, haddock, yellowtail, monkfish, scup, fluke and the list goes on. Swordfish swam close to Noman’s Land and in later years were found on the southeastern end of Georges Bank.

Mr. Mayhew said he believes the regulators’ effort to protect fish from overfishing would have been considered un-American in any other industry.

In their effort to protect fish, he said, regulators decimated the fleet, especially family-owned fishing boats. The small-time fisherman, like those fishing out of Menemsha, is really the endangered species, Mr. Mayhew said.

Even worse, he said, rewards were given to those responsible for most of the overfishing.

Mr. Mayhew said he and many other small-town coastal fishermen fished on many species during the year, never targeting one species.

But fishing changed in 1988, when the New England Fishery Management Council came down with a scheme of issuing permits to fishermen reflecting back history, past landings.

Fishermen were given a certain number of so-called days at sea commensurate to how much effort they fished on groundfish. Mr. Mayhew said that regulators credited those fishermen who fished cod the hardest with the highest number of days at sea.

But he and his brother were given 88 days a year to fish for groundfish. Then the regulators started tightening, lowering the number, to 48 days, as a way to cut down on effort to protect the troubled cod.

Areas of the ocean were closed. From the waters south of the Vineyard east to Georges Bank, regulators closed huge areas to fishing. The square miles of closed area is the size of the state of Massachusetts. And waters south of Nantucket that are the size of Rhode Island are closed to fishing.

Federal rules also inadvertently penalized the Mayhew brothers for keeping their boats in Menemsha. Every trip to and from New Bedford — for fuel and ice or to sell their catch, even though the nets were stowed away — counted against their days at sea.

“They rewarded the fishing boats that pounded the stocks when they were in the worst trouble,” Mr. Mayhew said. “Basically, the regulatory system made it financially unfeasible to make a living.”

Last winter, in an effort to try and get ahead, Mr. Mayhew arranged to have another captain operate the Quitsa Strider II out of New Bedford. Mr. Mayhew said he thought he could pull ahead if the boat was based in the city for the winter.

But mechanical problems with the boat and bad weather made it more than difficult. By the end of the five-month experiment, Mr. Mayhew said 50 per cent of all the receipts in fish sales went to pay for fuel. It didn’t work.

With no buyer for his boat, Mr. Mayhew said, he chose to sell his federal permits.

The permits were bought by the Gloucester Fishing Community Preservation Fund, Inc., a young organization that is buying up federal permits from fishermen as a way to preserve the commercial fishing fleet in that coastal city.

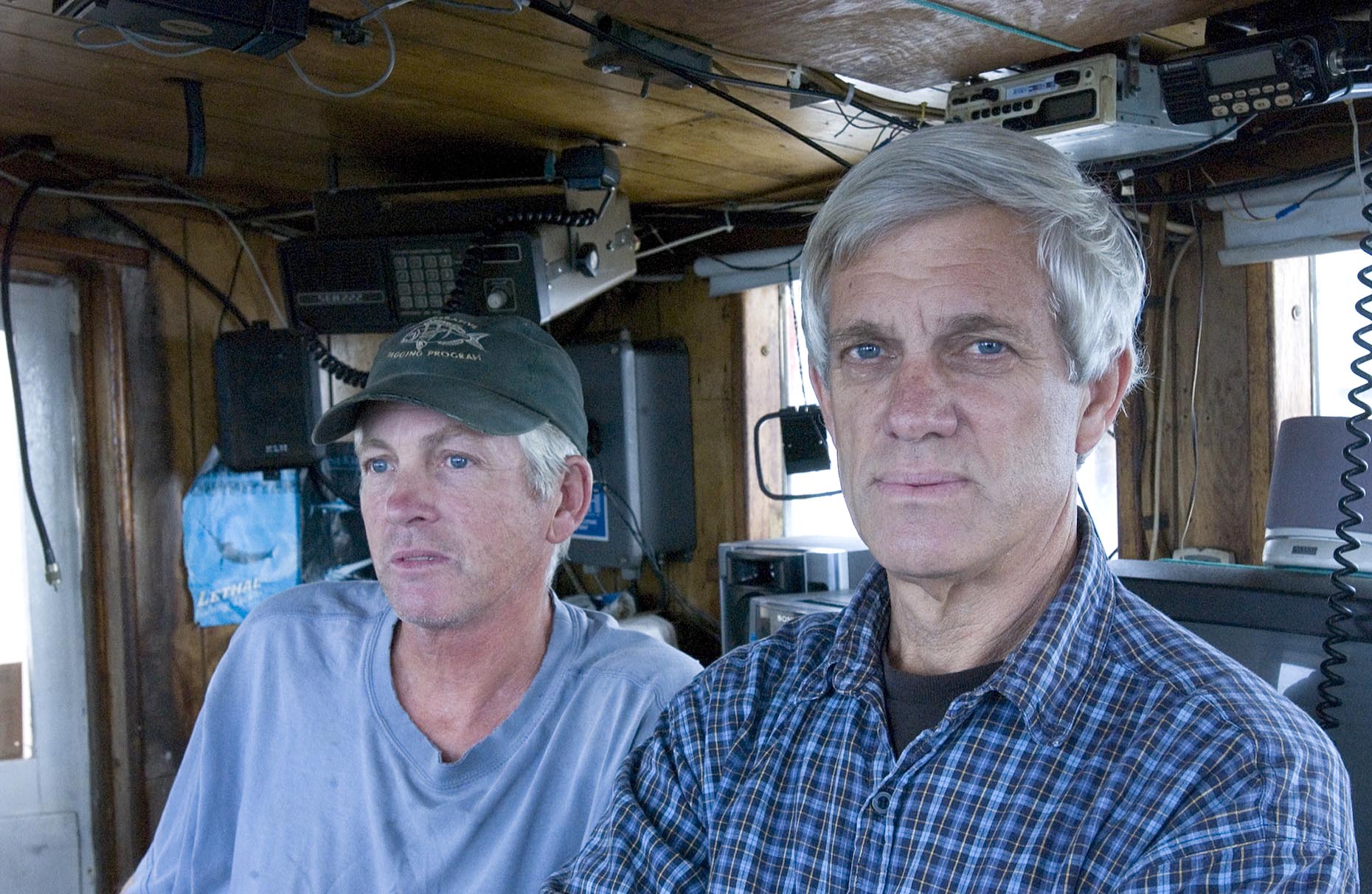

Bill Daniels of Athearn Marine Agency, who brokered the sale, said that a lot of commercial fishermen up and down the coast are doing what Mr. Mayhew is doing.

Mr. Daniels said Mr. Mayhew had few choices. One option: he might have bought or leased a permit from someone else to increase his days at sea.

Neither Mr. Mayhew nor Mr. Daniels would reveal the sale price of Mr. Mayhew’s permits.

But speaking generally about the industry, Mr. Daniels said, “When you talk about a boat of that size, they are paying around $150,000-plus for a permit of that kind.”

Mr. Daniels said leasing “days at sea” can cost as much as $500 for each day and if a fisherman has a bad trip, that can be a further economic disaster.

These days, Mr. Daniels said, he is brokering the buying and selling of federal offshore groundfish permits more than he is brokering the buying and selling of fishing boats. His agency has changed a lot since he began 30 years ago. At the company’s Web site, which lists a number of commercial fishing boats for sale, a boat similar to Mr. Mayhew’s is offered for less than $300,000.

Vito Giacalone is the acting executive director of the Gloucester fishing organization that bought Mr. Mayhew’s permit. He said the nonprofit firm formed last May.

“Gloucester is the oldest fishing port in the country,” Mr. Giacalone said. “We had hundreds of vessels for two centuries. In 1981 we had 138 mid to full-range sized trawlers. Now we have nine or 10. The fund was established, to do something extraordinary to retain fishing permits in this community.”

Mr. Mayhew said he was pleased by the sale to the Gloucester nonprofit, for he had heard that there was another big buyer, a seafood company in New Bedford, doing the same thing but for less exemplary reasons.

And this is what troubles Mr. Mayhew and others. The state of the fishery and the economic resolution that is being handed out will darken opportunities for young Vineyard fisherman who are thinking of making a living from the Vineyard waterfront.

If all the days-at-sea federal permits are bought up and consolidated by corporations, Menemsha and other small waterfront communities will be pushed out.

That has already happened in other fisheries. The sea clam fishery that includes some of Vineyard waters is already off limits, since only three large corporations own all the sea clamming permits for the Eastern Seaboard. The sea scallop fishery is already being managed with the effect of excluding small-time local sea scallopers from the fishery.

The future of groundfishing in the waters south of the Vineyard and all the way out to Georges Bank could end up the same way.

Those were all once-vibrant fisheries with Island fishermen making a good living. “Fishing was a good profession,” Mr. Mayhew said.

As for his own future, Mr. Mayhew said he is in the process of deciding what to do. He still owns a 32-foot fiberglass diesel fishing boat called Skillie, which he has used in the past for giant bluefin fishing.

Mr. Mayhew said he is concerned about the future Menemsha fisherman. They need flexibility, they need to have the ability to diversify their effort just as the Mayhew brothers did years ago.

“The young fishermen don’t have the flexibility we had and they never will,” Mr. Mayhew said. And that, he said, will leave them vulnerable.

Comments

Comment policy »