David Lebedoff is a Minneapolis attorney, political figure and writer known for provocative thinking. In the interest of full disclosure, he is also an old friend.

In his first book, The 21st Ballot, he argued that unseating officeholders in your own party primaries is a surefire recipe for disaster in a contested November election. Some McCarthy supporters in ’68 might have disagreed, but who won the election? In The New Elite, Mr. Lebedoff made a seminal attack on political correctness. Though he doesn’t have an explicit Vineyard connection, Mr. Lebedoff’s thinking is instrumental to those who approach every Island issue in an ideological straightjacket.

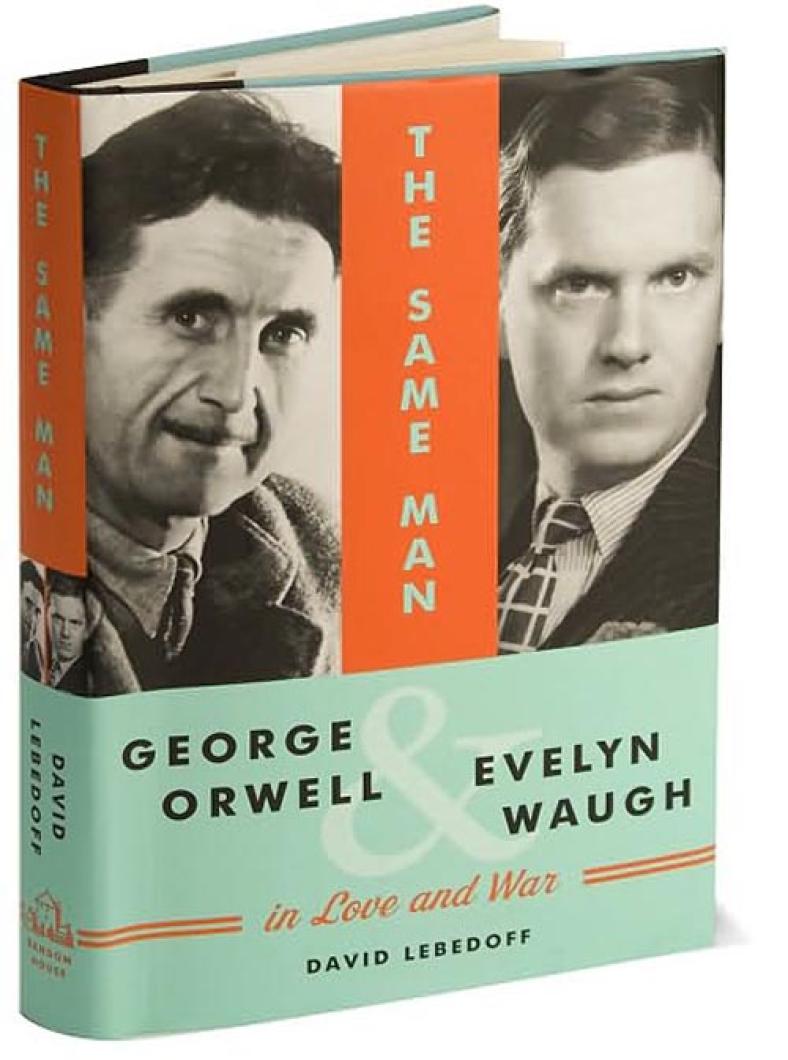

Now comes The Same Man: George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh in Love and War (Random House). The same man? Mr. Orwell (1903-50) was 6’3”, “soft and quiet and shabby,” an ascetic atheist and socialist who hated communism. Mr. Waugh (1903-66) was 5’6”, “hard and funny and elegant,” a sybarite, Catholic and conservative who admired Franco and Mussolini while hating Hitler. Yet Mr. Lebedoff makes a compelling case that the greatest political thinker and essayist of the 20th century and one of its leading novelists had more in common than their birth year. In the process, he gives us a summer surprise par excellence.

Born Eric Arthur Blair, the pseudonymous Mr. Orwell knew the sting of a country without a meritocracy. He was beaten, ridiculed and humiliated at St. Cyprian’s prep school, largely because he was on a partial scholarship. Though he was subsequently admitted to Eton, a passkey to Oxford or Cambridge, he was so disgusted by the class system that he turned his back on advancement in a society he loathed and never went to university. “The torments of school not only drove him to spend his life among the oppressed but also fueled his lifetime battle against the dictators who bullied entire populations,” Mr. Lebedoff writes. “If anyone tore down the Berlin wall, George Orwell did.”

By contrast, Mr. Waugh longed for higher education and bullied other boys at Heath Mount grammar school near home. Later, as a boarder installed for an extra 10 pounds in the headmaster’s house at appropriately named Lancing, he endured bad food and physical discomfort because he was in with the in-crowd of other bullies seen as financially privileged. While Mr. Orwell disowned Eton, Mr. Waugh pretended he’d been there during his foreshortened, self-indulgent career at Oxford. Devoted to pleasure at the expense of study, he dropped out when he realized that graduation in the third of four quadrants would do little for his career.

Here’s where Mr. Orwell and Mr. Waugh begin to merge. Mr. Waugh left school with little money and few prospects, landing a miserable job teaching Latin, Greek and history to boys at the second-rate Arnold House school in North Wales. By then, Mr. Orwell was a lowly officer among the Imperial Police in Burma. Mr. Orwell despised the British Empire; Mr. Waugh took notes that he turned into vicious critiques of a classist society. Mr. Orwell sought to escape from success, which he described as “man’s dominion over man.” Mr. Waugh was a social climber, but one who denounced the life he landed in.

While Mr. Orwell was ruining his health, experiencing poverty and writing books like Down and Out in Paris and London, Mr. Waugh launched himself into literary society with Decline and Fall, toasted by the critic and novelist Arnold Bennett as “an uncompromising and brilliantly malicious satire.” Then came Vile Bodies, which Mr. Lebedoff calls an indictment of an entire society: “At its heart, this ‘funny’ book contains a bleak world view. It makes it clear that the pointless frenzy of its fashionable young characters is the result of a moral void.”

And here, barely 60 pages into the book, Mr. Lebedoff marries Mr. Waugh to Mr. Orwell. “The aimlessness of life without faith, the impossibility of living without tradition, the triumph of might — all these ‘Orwellian’ themes are struck as well by Waugh in even one of his most frivolous comic novels.”

Both men were consumed by their work. Both believed in moral values over moral relativism, family and love over materialism and escapism. One of their most intriguing links was religion. True, Mr. Waugh cared only for the afterlife, while Mr. Orwell strived for a just life on earth. But Mr. Waugh believed “that Christianity provided the moral code on which Western civilization rested,” and Mr. Orwell felt that fear of divine retribution would lead people to good works in their lifetimes. Both men felt society depended on tradition and that its decline into materialism and escapism would produce a second world war. When Mr. Waugh, whose drinking and sloth left “merely an elbow likely to be approved for active duty,” won an officer’s commission through his contacts, the tubercular and unfit Mr. Orwell fumed, “Why can’t someone on the Left do something like that?”

Mr. Orwell and Mr. Waugh created private worlds for their families and relished the senses: in Mr. Orwell’s case an appreciation for plants, flowers and trees, in Mr. Waugh’s case, wine. Both men were masters of the pen. Waugh scored through savage phrases like “ostrich-cunning” and elegant passages like this:

“Mixed parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody else, almost naked parties in St. John’s Wood, parties in flats and studios and houses and ships and hotels and night clubs, in windmills and swimming baths, tea parties at school where one ate muffins and meringues and tinned crab, parties at Oxford where one drank brown sherry and smoked Turkish cigarettes, dull dances in London and comic dances in Scotland and disgusting dances in Paris — all that succession and repetition of massed humanity. . . .Those vile bodies.”

Mr. Orwell was at once clairvoyant and courageous. “There were plenty of journals on the left,” Mr. Lebedoff writes, “but not for a writer who saw Stalin in the same way he saw Hitler.” Willing to offend anyone’s views, Mr. Orwell wrote inelegantly but trenchantly. Comparing totalitarianism to democracy, he declared, “It is the difference between land power and sea power, between cruelty and inefficiency, between lying and self-deception, between the SS man and the rent-collector.” Mr. Orwell correctly saw kinship in Mr. Waugh: “In our own day, the English novelist who has most conspicuously defied his contemporaries is Evelyn Waugh . . . the only loudly discordant voice was Waugh’s.” The same, Mr. Lebedoff argues, was true of Mr. Orwell.

Mr. Lebedoff leavens his critical study with Mr. Waugh’s wit and Mr. Orwell’s wisdom. He says of Down and Out in Paris and London: “ . . . still recommended to those who need to lose weight.” Describing Waugh’s attack on his own cushy lifestyle, the author says, “The Age of Aquarius was not for him; he preferred Aquinas.” In his critique of today’s intellectual elite that substitutes diplomas for merit and political correctness for morality, Mr. Lebedoff writes, “The elementary rules of common sense would probably have prevented an American land war in Asia and, years later, the precipitous effort to transplant democracy to sandy soil that had never sustained such roots.”

One struggles to remember that the three of them — the author and his subjects — are and were only human. I wish Mr. Lebedoff had more lengthily documented his assertion that the Republican and Democratic party structures are controlled by extremists (perhaps that’s too large a subject — grist for another book), that Mr. Orwell had refused to supply the British Foreign Office with names of suspected communist sympathizers, and that Mr. Waugh had been nicer to people.

These are minor quibbles about major men. What an odd couple our cover boys were: the taut Mr. Orwell, who, Mr. Lebedoff says, resembled Stan Laurel, and the corpulent Mr. Waugh, a regular Oliver Hardy. They admired each other’s work and finally met at Mr. Orwell’s deathbed. They were the same man, or close enough. Believe it.

Jim Kaplan is the Gazette’s bridge columnist and co-author, with Bill Chuck, of Walkoffs, Last Licks and Final Outs: Baseball’s Grand (and not-so-grand) Finales (ACTA Sports, 2008).

Comments

Comment policy »