Cuttyhunk island, lying seven miles off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard and 14 off New Bedford, is connected to the coast by one ferry line and the services of charter fisherman. Since the 19th century, well after its initial discovery by Bartholomew Gosnold in the 1600s, the island has been a bastion of traditional Yankee fishing history and old-world character. This quaint fishing island was once referred to as New England’s own treasure island by a New England textile tycoon whose imprint remains indelibly stamped in the island landscape.

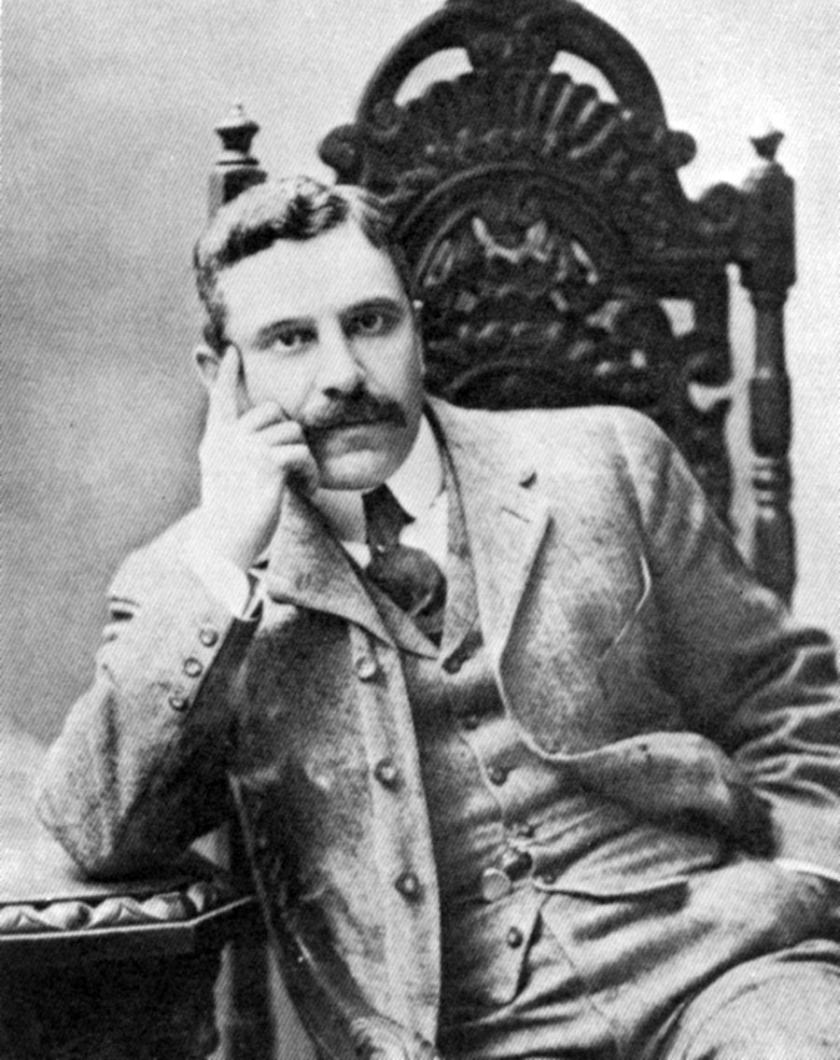

William Madison Wood is not an unknown name in New England. Born and raised on Pease’s Point Way in Edgartown in 1858, he became the president of American Woolen, a textile company, and perpetuated the legacy of the Massachusetts mill system at the turn of the 20th century. Emerging from humble Portuguese heritage, a personal hindrance in the business world, William Wood officially entered the world of textiles through his marriage to Ellen Ayer. The Ayer family was well-known in New England.

The Ayers, under the auspices of Mr. Wood, funded the merger of several struggling New England mills. Guided by Mr. Wood’s deft hand, the American Woolen Company was established in April of 1899. The business expanded successfully over the next 20 years, bringing money and a reputation of success to the Wood family. By 1923, Mr. Wood would own and operate 60 mills in eight states.

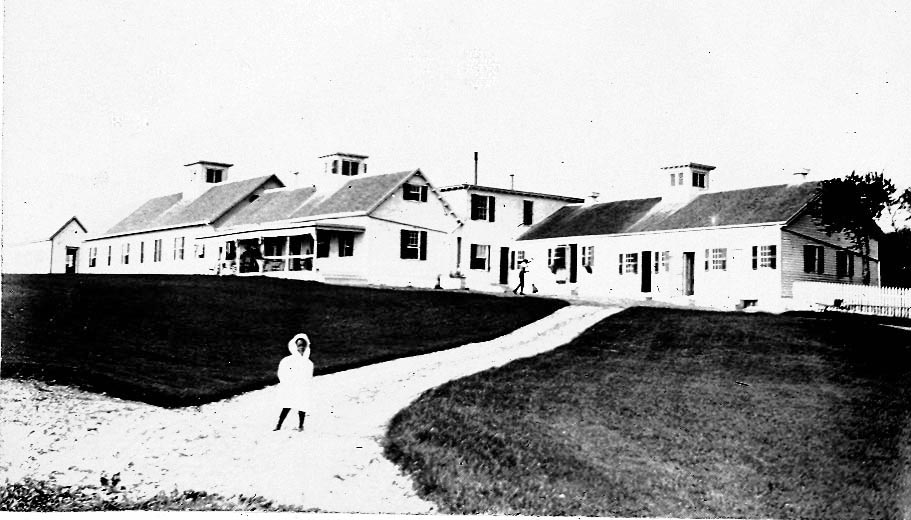

Mr. Wood came to Cuttyhunk in 1904, probably drawn by the desire to build a haven far from the bustle of industrial New England. He stayed for several nights at the Cuttyhunk Fishing Club and returned for a second visit. At the time, the island was a thriving fishing village and a seasonal place of lodging for off-island tourists. Despite his wife’s dislike of the remoteness of Cuttyhunk, Mr. Wood began purchasing parcels of land in 1905.

The Cuttyhunk Fishing Club captivated his interest and he made several attempts to join and purchase the exclusive club, but with no success. The Cuttyhunk Fishing Association was known as The Club to the New York sportsmen who joined a legacy of anglers who had established the organization in 1864. It served as a fishing retreat for elite gentleman. With annual dues around $100, club membership numbered between 50 and 75. Members fished for the plentiful striped bass which ran thickly around the island. The shoreline paralleling the club was dotted with stands built over the rocky shores where members were able to perch over unobstructed water to fish for stripers.

While there is no recorded historical evidence explaining Mr. Wood’s rejection from the club, islanders and historians believe that despite being an ideal candidate for membership — elite and successful — Mr. Wood’s ethnic background was a factor in the rejection. A scholarly journal published by the Portuguese-American Society documented his Portuguese heritage.

In several early 19th century issues of Who’s Who in New England, entries on Mr. Wood were published with no mention of his heritage. In more than one published account, his mother was described as English and Scottish. It is possible that Mr. Wood associated success with a Yankee background and found it an asset to reestablish his ancestry as Anglo-Saxon in the New England business world.

Regardless, he used his resources to establish himself on the island. In 1907 and 1909, he bought two large parcels of land from local families and began construction on a large summer residence for himself and his family, very near the fishing club that had rejected him. By 1912, the Wood estate, called Avalon, was complete and cast its shadow over the fishing club lands.

During construction, a kind-hearted working relationship was established with the Cuttyhunk community. Mr. Wood employed locals to provide a gamut of services; he hired caretakers, a captain for his personal ferry and domestic service staff for both Avalon and the Winter House, another lavish estate which began construction in 1917 as a wedding present to the youngest Wood son, Cornelius Ayer, when he married Muriel Prindle. Along with the two summer homes several supplementary buildings included a bowling alley, paint shop, dairy, powerhouse, and Winter House Annex — a private office and barbershop. The bowling alley, now a private residence, recently went through an historic renovation.

Granville (Francis) Jenkins, a local face on the island in the early 1900s, first arrived when Mr. Wood was beginning construction on the Winter House. He stayed on, working for Mr. Wood as painter and eventually caretaker for all the Wood properties. According to Betty Jenkins, daughter in law to Francis, he was known for mixing and supplying the universal shade of gray used on the local buildings. “He used to go around the island and say: ‘Well boys, what shade of gray do you want this year?’ ” she recalled. He was one of the most well-liked residents.

As attendant for the powerhouse, Francis also used to spend his evenings there. The plant ran on DC power during daylight hours and switched to battery at night, “At 10 p.m., he would flash the lights to warn of the switch, and then the power went off,” Betty Jenkins recalled.

She said the Jenkins family had a long working history with the Wood family. Walter Jenkins, the first member of the Jenkins line to live on Cuttyhunk, helped build Avalon. David Jenkins, Betty’s husband and son to Francis, ran the powerhouse after his father’s death. Betty worked as a cleaner and server in the Winter House. “[William Wood] was quite a man . . . [they all] had a wonderful working relationship,” she said.

Although strictly a summer resident, Mr. Wood contributed generously to infrastructure improvements on Cuttyhunk. Not only did the town eventually purchase the powerhouse which currently provides electricity to the entire island, but the power lines were installed underground. He also financed a town sewer system.

During the 1920s, while American Woolen continued to prosper in the aftermath of war production during World War II, preliminary clearing began on a third Wood house at the highest point on Cuttyhunk. This house was intended as a gift for the eldest Wood son, William Jr. Imported Italian stone workers built decorative stone walls which lined the road leading up to the house. But construction halted soon after the death of William Jr. in a car accident in 1922.

Several years later, William Wood retired with some pressure from investors, and named his son as successor to American Woolen. He died in Florida in 1926. His family continues to have a presence on Cuttyhunk; his granddaughter, Muriel Wood, daughter of Cornelius Wood, summers on the island with her family in the Winter House.

And as before, islanders and the Wood family continue a relationship of mutual respect. The Wood family is often seen as a steward of island land, safeguarding it from strangulating development.

Sarah Monast is a graduate of the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School and Wheaton College. She works at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

Comments

Comment policy »