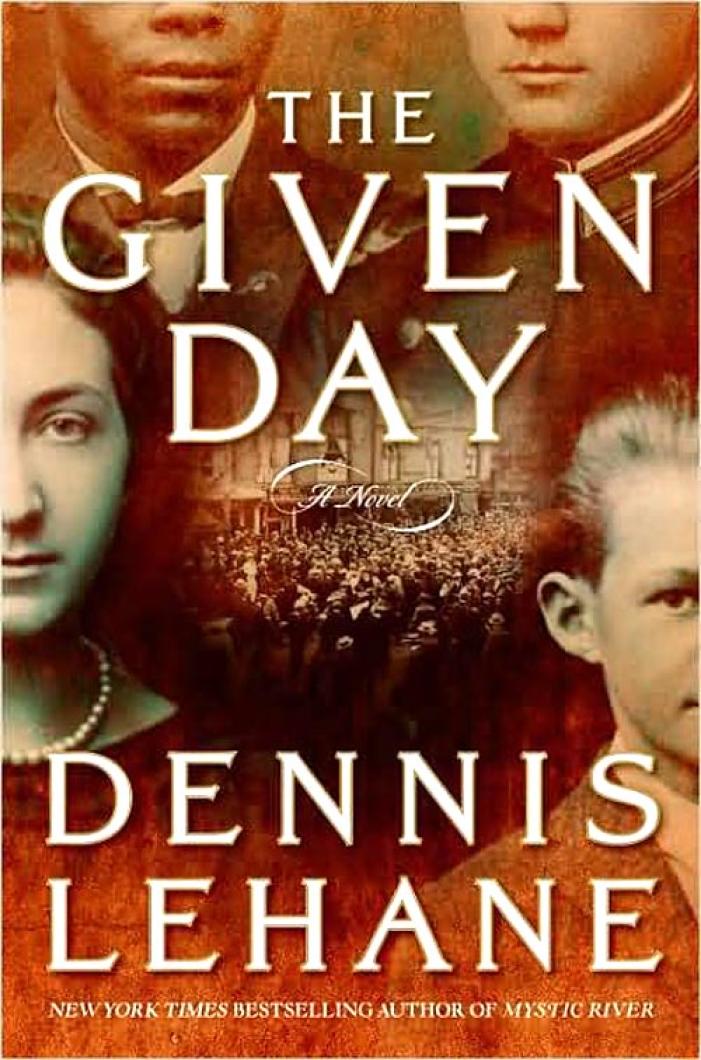

Dennis Lehane took a piece of Boston history, the stuff of legend in the city’s neighborhoods for nearly 90 years, and has written it as an epic novel.

Called The Given Day, the novel will be released today by William Morrow.

Readers who grew up, as this reviewer did, listening to the old tads talking about the riotous times in Boston after World War I will find their oral history about the Boston police strike, Spanish flu epidemic and several years of bombings of public buildings by assorted revolutionists, put in place and perspective in The Given Day.

For those who haven’t the history, the book is a whole-cloth story of America and American cities at the turn of the century. Its characters include national figures and icons who dominated the American scene for decades afterwards.

J. Edgar Hoover shows up as a peckish, haughty federal agent intent on building a career based on fear, information and disinformation. Governor John Calvin Coolidge is shown as a pitiless politico, fine-tuning his presidential hopes by allowing a city to go mad for three days before taking action. Woodrow Wilson, then attorney general, is fixated on destroying sedition and seditionists wherever he finds them — or thinks he has found them.

Sports icon Babe Ruth, then a Boston Red Sox player, shows up in all his power and frailty, cast in a moral conundrum around racial attitudes. Mr. Ruth’s choices are in contrast with the characters of W.E.B. DuBois, founder of the NAACP, and African American fugitive Luther Laurence, who leaps from the frying pan of the segregated South into the fire of Boston’s early 20th century discord.

The Given Day is ostensibly the tale of the three-day Boston police strike in 1919 and the months leading up to it, but it’s a rugged landscape that also features nearly 300 years of class struggle between the Brahmin Yankees and relentless waves of Irish immigrants.

An acclaimed storyteller (Mystic River, Gone Baby Gone and other Boston-based detective yarns) and a product of a Boston Irish neighborhood, Mr. Lehane centers his story around the Coughlins, a cop family from the North End slums who have moved up town to a fine house in South Boston, fueled by cunning and canniness and funded by years “on the pad” —largesse from kickbacks and payoffs.

But make no mistake, the department and its leaders were just as committed to keeping the peace as they were to lining their pockets. Lining their pockets and climbing the ranks was the way out from working 14 to 19 days without a day off and sleeping at the station house in rotating shifts on lice-ridden cots for subminimum wages.

Those who made it out of the station house were not going to give up their cash and prizes.

The Irish immigrant patriarch, Thomas Coughlin, is a precinct captain in the department. Running a precinct was a position in those days (and some might say these as well) akin to being a prince in a feudal monarchy.

Danny Coughlin, the son, is a star-quality patrolman but a maverick who must choose between a desire to improve conditions for his mates on the force and a quick ride up the ranks of the tribal Irish police department.

Fans of Mr. Lehane’s gritty detective and crime thrillers will like The Given Day. They will also note that Lehane’s writing game has gone to another, higher, level.

Mr. Lehane has done for the generally dry historical accounts of the period what Kevin Baker’s 2002 novel Paradise Alley did for Herbert Asbury’s Gangs of New York. And like Paradise Alley, which recounts New York draft riots in the 1860s, The Given Day is alive with plenty of subplots and tension to keep the savviest mystery readers turning the pages.

His descriptions of the living of life in Boston’s poorest neighborhoods are startling. Other than a few neighborhoods such as Beacon Hill, Mr. Lehane describes a city that was neither quaint nor idyllic.

Historical fact is often a casualty in historical novels. Not in this one.

Mr. Lehane did the formal research. His depiction of events certainly squares with the stories I heard growing up in South Boston from my parents and from my grandfather, Joseph T. Geary, who was a Boston patrolman from the turn of the century until the early 1940s.

Joe Geary came to Boston as a 14-year-old runaway, endured the Irish-Need-Not-Apply days and thought that being a cop was better than being the Pope. He passed the sergeant’s exam three times but would not make the $350 payoff to get on the list. He walked a beat for 40 years.

More than 1,100 cops went on strike on Sept. 9, 1919. Patrolman Geary was one of 300 cops who did not strike. He spent three days in the streets while a national guardsman stood sentry in front of his wife and five children at his East Second street home.

Joe Geary would have liked Mr. Lehane’s book, I think.

Comments

Comment policy »