John Sundman is a Tisbury-based science fiction writer. He has recently self-published his third book, The Pains, a dark, satirical vision of 1984 America that blends George Orwell’s classic dystopia with a surreal version of the real-life Reagan-era. According to the author, it is a “story of faith in a world that appears to be falling apart. It tells the story of Norman Lux, a 24-year-old novitiate in a religious order, who becomes afflicted with something akin to stigmata.”

His first two books, Acts of the Apostles and Cheap Complex Devices, have netted Mr. Sundman a small but devoted worldwide readership. He has written for Salon.com and other magazines, and is currently a volunteer at Island Food Pantry and the Serving Hands pantry, and a member of the Tisbury Volunteer Fire Department. Here, he talks about his work and life on the Island.

Q: You have an online reputation as a “gonzo sf” [sci-fi] writer; how do you feel about it?

A: The writer/activist Cory Doctorow first called me that on his site Boingboing.net. The term implies a kinship with the late Hunter Thompson, who was called a “gonzo journalist” for his take-no-prisoners style of investigating and writing stories. I think people call me a gonzo writer because I write wacky stories, and because I write about science and technology in the language that scientists and technologists actually use. I don’t “dumb it down” as some publishers have suggested I should. I publish my books myself and sell them like a peddler at geeky conventions and street fairs. I’m not too proud to make a spectacle of myself if it will help me sell a few books. Also, I was one of the first writers to make all of his books available in electronic form online for free under the Creative Commons license. I said, “What the hell. I’ll give them away and see what happens.” I guess I’m not very conventional in how I write or how I publish my books. So I take “gonzo” as a compliment.

Q: What about self-publishing? How do technology, e-books and Internet distribution/promotion change the way authors can get their work out? Who wins and who loses? Where might it go from here?

A: Those are the $64,000 questions, aren’t they? I make my books available in HTML format initially, and PDF eventually, free of charge. I have not yet made Kindle or other versions for mobile phones and other portable devices. I understand that such versions of my books are out there on the Net. That is to say, people have taken it upon themselves to reformat my books and make them available to others — for which I get no monetary compensation, of course.

I may or may not get around to making Kindle or e-ink versions of The Pains. First I’ve got to look into the economics of it to decide whether it would be worth the trouble. Writing the book, arranging the illustrations, preparing the manuscript for publication and arranging the printing and binding has been work enough, thank you very much. When I announced The Pains a few weeks ago, within a day I had half a dozen e-mails from random people asking me where the Kindle version was — as if I owed it to them to give them my book in their preferred format. My response was, “I just gave you a free book. If you want a Kindle version, make it yourself.”

So I don’t know where publishing goes from here. But I do know one thing: small-time, or “mid-list” authors like me, if they’re willing to hustle, can make more money publishing their own books than they can make with traditional publishers. Big name authors — the Tom Clancys and J.K. Rowlings — of course do better with traditional publishers than they could do as their own publishers, because prominent authors like Clancy and Rowling get giant advances and their books are made available in bookstores everywhere. But obscure little authors like me, on the other hand, get only tiny advances, and the royalties paid to people like me amount to mere pennies per book sold, as opposed to dollars per book sold you get when you cut out the middleman and publish yourself. And if our books make it to bookstores, they generally don’t stay there long. With traditional publishers, books are given only a very short time to find their audience. If they don’t find it, the books are pulled and pulped to make room for somebody else’s new masterpiece. But when you’re your own publisher, you can keep your books in print as long as you like. My own Acts of the Apostles, which came out in 1999, is still in print.

The downside to self-publishing, of course, is that distribution through bookstores is virtually impossible. My books are available through Bunch of Grapes, Amazon, and my Web site, wetmachine.com. That’s it, unless you catch me at a trade show or street fair. Bookstores can order from me, of course, but they generally do that only when they get a special request. They don’t keep my books on their shelves.

Most of my sales come through my Web site. People hear about my books some way or another, read a portion online, then decide to purchase a paper copy, which I inscribe to suit. I’ve shipped books to Mexico, Canada, Sweden, Switzerland, Portugal, Korea, the UK and about 30 U.S. states. For some reason I cannot figure out, I have lots of fans in Toronto, Ontario and in Sydney, Australia. I’ve had hundreds of e-mail chats with my readers. That’s extremely gratifying. And I’ve been asked to write some pretty funny inscriptions, which I have always been happy to do.

Even though I have no bookstore distribution, I still make more money self-publishing than I would with a conventional publisher. Random House came calling a few years ago — an editor phoned me out of the blue to ask if I would sell the rights to my books to them — which was very flattering. But after a few meetings with New York city editors, I realized I already had a better deal working for myself. Like I said, I’m a minor-leaguer. If I ever make it to the big leagues, I’m sure Random House will offer a much sweeter deal, and I’ll be happy to take it. But for now, I’m ... having more fun, than I would as a Random House author.

Q: You went to high school in Manhattan, studied agriculture in college, did development work in rural Africa, then started a career in computer science and became a part of the Silicon Valley tech boom. How did John Sundman end up living on Martha’s Vineyard, working for the fire department?

A: First, although I’m extremely proud to be a Tisbury firefighter, I don’t work for the department, I’m just a volunteer and I’m only a red-tag rookie at that. I have a year’s training ahead of me before I can even get a yellow tag, which would allow me to get close to a working fire. I should have joined 16 years ago when I moved here, but thought I was too old!

As to how I ended up on Martha’s Vineyard: my wife, Betty Burton, and our children and I had vacationed here a few times in the 80s — in a tiny bungalow on William street. In those days I was managing a large bi-coastal engineering group for a multinational computer company. Our family lived in central Massachusetts. I had one office near Boston and another one in Silicon Valley and I was flying across the country 15 times annually, spending about 100 nights each year in hotel beds from Sunnyvale to Redwood City. In 1993 my company relocated us to California — and then they laid me off in 1994! At the same time my wife’s business went bust, taking our life’s savings with it. On top of everything else, one of our children was experiencing severe health and disability challenges. We were homesick for Massachusetts. So we came to the Island for the good schools, the sense of community, and to get as far away from the rat race as we could. The plan was for me to make a living writing books about how to manage software projects. It didn’t quite work out that way; I ended up being a pallet jockey in a food warehouse, doing construction jobs, being a helper on UPS delivery trucks, and driving a moving van for Trip Barnes! Eventually I went back to high tech [for] a software startup in Cambridge, near MIT, and from 2003 to 2007 I worked for another software startup based in California. I would go to the California office eight or ten times each year, but mostly I worked from my living room in Vineyard Haven, in my p ajamas. Lately I’ve been doing some work for Intel. I’ve never met the people I work for or with at Intel, who are in Oregon and California.

You’ll note, by the way, that I got out of high tech for the first time right at the start of the big boom of the mid-to-late nineties. I didn’t even know the boom was going on, frankly, that’s how completely I had left that world. I had dropped out and never thought I would go back. One of the many reasons I’m not rich today.

Q: Many writers and artists find the natural beauty of the Vineyard inspiring. Does the Island affect the way you write?

A: I don’t much write about the Vineyard, although I have noodled around with the idea of writing some kind of Stephen King type horror story set on Noman’s Land. I know a few other writers who live here, and I like being in a place where being a writer doesn’t make you a total weirdo. But I don’t hang out with a literary set. There are lots of writers here that I’ve heard of but have never met. Mostly I’m hoping some of the magic from people like William Styron and Dashiell Hammett will somehow catapult me to literary stardom. If that happens, I’ll be sure to let you know.

I do like the community sense here. My wife and I run a food pantry and the “family to family” [food assistance] program; we’ve been co-presidents of the Tisbury PTO, I’ve been a Boy Scout leader, I’m a volunteer fireman, my wife runs the evening lecture series at the library. Lots and lots of people are similarly connected. I like it.

Q: What is your favorite place on the Island?

A: Perhaps The Devil’s Ampitheatre, which is a natural formation, a kind of giant bowl with an opening to the beach, in the dunes near Squibnocket Point. It is, alas, on private property. I explored that area during breaks on a construction job a few years ago; in fact I was in the amphitheatre during Hurricane Floyd in 1999, and it was like being on the moon or something. Locals tell me that decades ago it used to be a popular spot for teenagers to party — but only for those who had the stamina to walk or boat there, there’s no easy route by car. I have a fantasy some day that the Devil’s nominal owners will do the right thing and donate or sell this land to the land bank. It’s a sacred place that should belong to everybody.

Q: Speaking as a futurist, what does the Vineyard look like in 100 years?

A: George Woodwell, the founder of the Woods Hole Research Center and a legendary climatologist, ecologist, and environmental activist, is a friend of mine. He says that we must either make the earth a park, or watch it collapse into what he calls “the Haitian abyss”. It’s a binary choice: options in the middle have vanished; there will be no muddling through. As a species, we have only years, not decades, to decide which future we’ll have. I’m an optimist by nature, but I’m scared. If we humans don’t get a handle on climate change, Martha’s Vineyard 100 years from now will be some version of hell, like Haiti, only worse, as will every other place on earth. Otherwise, it will be some kind of paradise, much as it is now. As for science-fictiony developments like the merging of machine and human intelligences, transhumanism, personal immortality, I have nothing to say about them at the moment. That stuff creeps me out, even though I make my living writing about it.

Q: What’s your favorite excerpt from The Pains?

A: I very much like the opening sentence, which I borrowed from somebody’s online diary about a dream. It sets up the whole premise of a metaphysical condition threatening physical reality. I’m also happy with the scene where the monk Mr. Lux and the scientist Xristi first meet each other in a yuppie bar. There are three entirely different worldviews in that room — his, hers, and the bar patrons’ — and each seems normal to the person who holds that view and absurd to everybody else. So the writing challenge was to make the absurd seem normal, and to make the reader believe that such a conversation could actually have taken place as I describe it.

Q: In one sentence, why should people read The Pains?

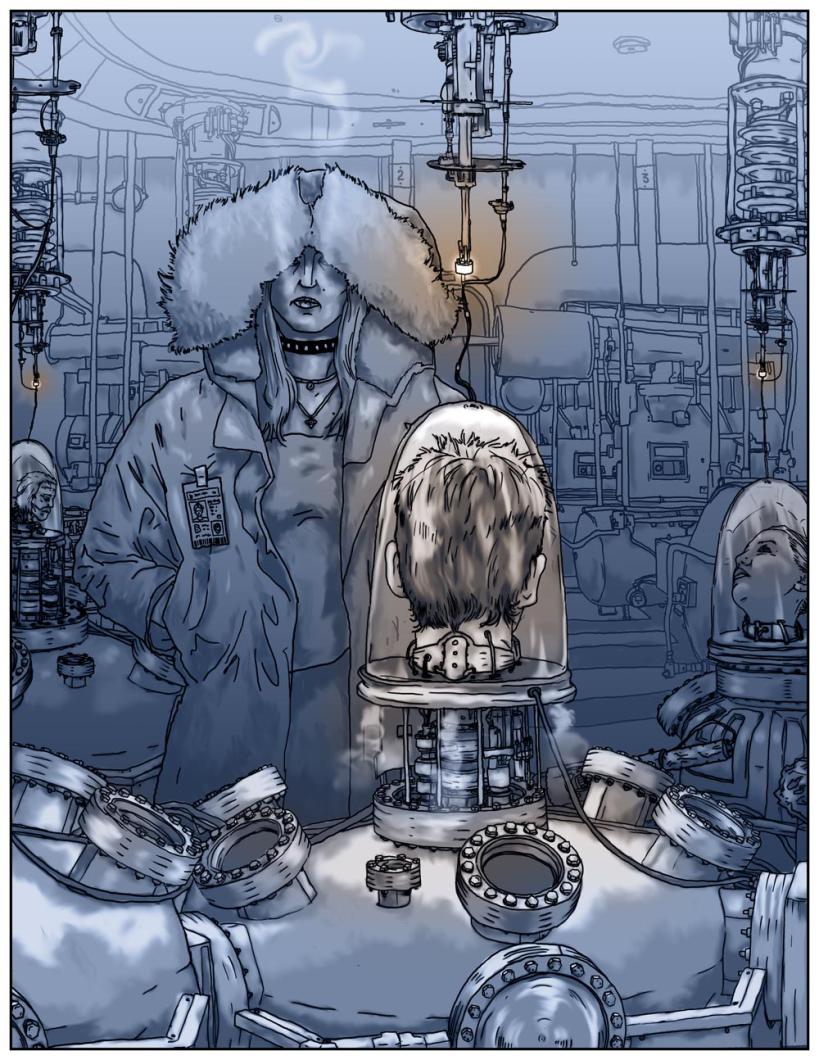

A: It will help them better apprehend the urgent message of George Orwell’s 1984, which has been lost to over-familiarity. Also, The Pains is fun and creepy-cool and the illustrations will give you nightmares and disturb you for days, if not weeks or months. Okay, that’s two sentences. Sorry.

Q: Speaking of illustrations, what made you decide to include pictures in The Pains, and how did you find illustrator Cheeseburger Brown?

A: The Pains is more of a fable, or a comic book-type story than a proper novel. It’s really more like a dream, the kind of story one sees in graphic novels these days. Since it was halfway between a literary novella and a graphic novella I decided to split the difference and put in a dozen illustrations.

Cheeseburger [and I] both hung out in the same online community for years. I was at a wedding a few years ago between two members of this same community, and one of the gifts was a large painting by Cheeseburger. It was so creepy I could hardly stand to look at it ... I knew right then that I had found the right artist for The Pains.

To purchase the book, or to download an electronic version for free, visit wetmachine.com/ThePains/index.html.

Comments

Comment policy »