I went to the inauguration thank s to my college friend, David Skaggs, a former Colorado congressman, now the chairman of the board of the newly established Office of Congressional Ethics. From Republicans who had other things to do, David accumulated enough tickets to invite not only his own family but a group of Wesleyan friends as well. Though I dislike crowds to the point where I leave that cannot-be-named-in-this-newspaper stadium in the Bronx at the end of the seventh inning, I knew I was being summoned by history.

If you’re reading this, you have also watched hours of inauguration coverage and have read floods of words. To be there was to be part of an electric crowd of instant friends. The emotion was overwhelming: as we waited to go through security in the Longworth House Office Building, the crowd spontaneously broke into We Shall Overcome, followed by, among others, The Battle Hymn of the Republic, and Michael, Row Your Boat Ashore. Outside, seated in the bitter cold (I’d bought new thermal underwear), people exchanged e-mail addresses and took pictures of each other and promised to send them. To keep warm, the crowd chanted “O-bam-a!” as if waiting for a storied slugger, capable of knocking one out of the park.

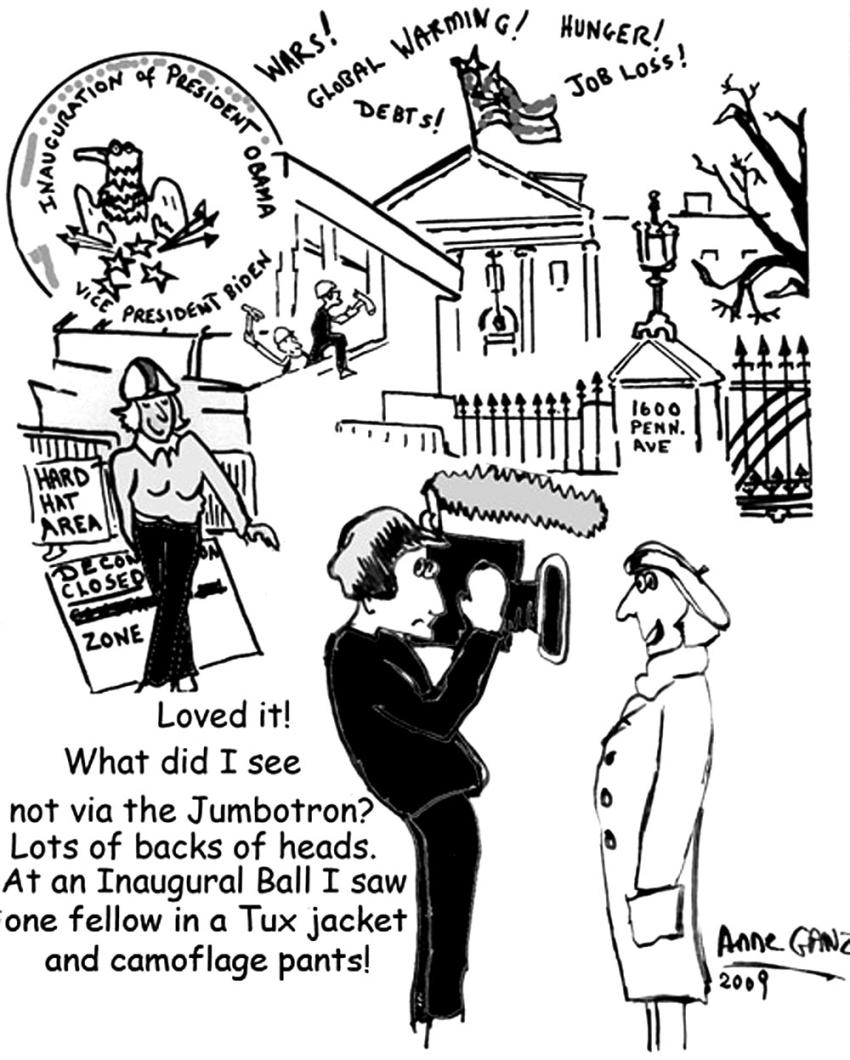

The disdain for our outgoing president was palpable. Most people were respectful, withholding applause; some booed. Later, as the Jumbotrons showed the Bushes departing by helicopter as it flew over us, many stopped to wish the former president a categorical goodbye.

In sum, people were ecstatic — congratulating each other on what “we” had wrought, forgetting what “we” had also wrought, or acquiesced to, in 2000 and 2004, which created the imperative and conditions for a watershed election in 2008.

“A republic, if you can keep it,” Benjamin Franklin replied to an inquiry at the close of the Constitutional Convention about what kind of government was to be recommended to the former colonies. Franklin’s remark is as pertinent in 2009 as it was in 1787. For whenever we inaugurate a new president at least a plurality of us is hopeful that he, not yet she, will be an improvement over the outgoing president. The clock cannot be turned back but it can be reset. We begin anew.

For the first time in many elections, a majority of us rather than a mere plurality is united in hoping that President Obama will preside over a rebirth of the American republic that was once the envy of the world. Congratulating ourselves on returning it to more qualified stewards, however, is insufficient to the damaged condition of the republic President Obama inherits. It is essential that we reflect about how it happened, certainly not for the first time, that the electorate (we who must keep the republic) twice elected an inferior candidate, one who upon taking office determined to govern by fervor rather than by fact.

America has paid dearly — in lives, in fortunes, in sacred honor — for such indifference by its citizens to that most exacting responsibility, exercising our votes wisely. Bob Herbert put it bluntly in a recent New York Times column: “It’s time to stop being stupid.” President Obama, echoing Franklin, reminded us Tuesday of “our collective failure to make hard choices . . .”

We invest presidents with unrealizable hopes, sometimes with magical powers. He is not only our chief executive, but also our ceremonial head of state. Beyond those codified functions, however, the people look to him to be, as Clinton Rossiter so aptly phrased it, “a combination scoutmaster, Delphic oracle, hero of the silver screen, and father of the multitudes.” That is a tall order.

President Obama has a first-class intellect. He appears, also, to have a first-class temperament, two components rarely fused into a president. (The retired Justice Holmes observed, upon meeting president-elect Franklin Roosevelt, that FDR had “a second-class intellect but a first-class temperament.”) That President Obama embodies these qualities does not guarantee deliverance from what ails America. Presidents are not magicians. They cannot transform alone, without the cooperation of a Congress that truly practices its representative function. The principal danger to keeping our republic is the politics of ideology: that America has a mission to export democracy to other, lesser societies, that faith or gut-based decision making is the equal of informed, analytically challenged and refined decision making, that issues like reproductive and gay rights are something more than basic human rights and should be litmus tests for elected officials and judges. At our peril, forgetting Jefferson’s implicit warning, do we allow every difference of opinion to become a difference of principle.

Politics, elections and therefore government itself is the art of the possible. No president can succeed without a knowledgeable, engaged citizenry. Being effectively governed is, indeed, about asking what you can do for your country — and the least any citizen can be is informed and engaged.

We must beware of ideology and skeptical about certitude (both our own and that of our representatives); we must adapt old opinions to new realities, recognizing that there are few, if any, eternal verities. We must support our opinions by more than beliefs or feelings. Above all else, we must be able to identify nonsense and oppose it actively.

It is right to be hopeful especially if the alternative is to be despairing. President Obama takes office 200 years after Lincoln’s birth, without whom the Union would have disappeared into the maw of sectionalism. He takes office 76 years after another man, from another Hyde Park, came to the presidency proclaiming that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. But hopeful auspices are transformed into a better future only by hard work.

We the people. Government of the people, by the people, for the people. If we accept these foundational tenets of American democracy, it is never correct to assert that government is our problem; it is only correct, as our new president says, to ask whether it works. The people get the government they elect. In late 2008, we the people came together, pierced the veil of cant and the shameful character assassination tactics of our presidential politics, and embraced — fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray — a better angel of our national aspiration.

Nicholas Puner lives in West Tisbury.

Comments

Comment policy »