A bowl of steamed blue mussels is among the most valued culinary seafood dishes on the Island. Just about every restaurant that serves seafood offers the bivalve. But all of the mussels consumed on the Island comes from afar, nearly all from Canada. But in the years ahead the popular shellfish may be raised and harvested here.

A group of spirited Island commercial fishermen, with the help of the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group, plans to start an experimental blue mussel farm in state waters off the coast of the Vineyard this summer. The proposal is part of a larger project to bring blue mussel farming into the region, and it is funded through the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration’s nationwide effort to promote sustainable aquaculture.

The proposal is before the Army Corps of Engineers and a public comment period has begun. The permitting process underway seeks to establish three sites in local waters: one site three miles off Aquinnah, another three miles off Chilmark, and a third one mile off West Tisbury in Vineyard Sound.

Rick Karney is director of the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group, the lead nonprofit organization involved in the effort. Mr. Karney normally spends the year with his staff raising millions of baby bay scallops, quahaugs and oysters at the shellfish hatchery on Lagoon Pond. The baby bivalves are then turned over to local shellfish constables, who then distribute them to the Island’s inshore waters. He rarely comes in contact with blue mussels, for they are more of an open ocean resource.

Martha’s Vineyard offshore waters are ideally suited for raising blue mussels. They are already here in the wild, already naturally growing on buoy lines and underwater rocks. But there are no commercially viable blue mussel shellfish beds.

Interest in raising blue mussels arose in a circuitous way. Two years ago, the Chilmark selectmen, concerned about the future of the town’s greatest asset — its harbor — took on an effort to research ways to keep Menemsha a working fishing harbor. With declines in both fish and local fishing boats, a question was raised about whether raising and harvesting blue mussels offshore was an option. There were talks.

Already the inner coastal ponds were busy with recreational boaters and a multitude of uses and a small group of oyster farmers. Looking for an offshore option seemed a natural next step. Interest shifted to a successful commercial blue mussel aquaculture program in the waters off New Hampshire, in the Gulf of Maine.

Two summers ago, sample buoys were place in the waters off West Tisbury, Chilmark, Aquinnah, and even off Noman’s Land. Though a small endeavor, the results were positive enough to warrant further work.

Mr. Karney said this summer the group would like to establish two demonstration farms. The farms, though small, would incorporate the use of two underwater systems spanning about 600 feet. “There will be one on the north shore and a second on the west shore,” Mr. Karney said. It is not yet clear which of the two Vineyard Sound sites will be used first. Also undecided is which of the fishermen will be involved in the experimental project. “We have a group of fishermen who have expressed interest from day one. There are as many as eight or ten involved. Some of them went up to New Hampshire to visit the blue mussel farm.

“We are looking for fishermen who have the time, who have the boat capacity and are interested,” Mr. Karney said.

After monitoring the growing rates of the blue mussels in the experimental program over the past two years, Mr. Karney said they believe it only takes a short time for juveniles to feed and become adults.

“In the first year we will seed. We put the juveniles in socks and attach them to the lines. If it works, they should be harvestable in a year,” Mr. Karney said. Blue mussels normally spawn in early April or May, though Mr. Karney said there is evidence that they could spawn all the time. Once the farm is established, it would continue to feed itself.

A fisherman would revisit the site from time to time over the course of a year to make sure it is operating properly. He’ll collect the product whenever he hauls up the line, harvesting the adults and making sure that there are plenty of juvenile blue mussels coming along. “It would be a continuous and sustainable process,” Mr. Karney said, adding, “Shellfish aquaculture is environmentally benign and probably beneficial to the environment.”

The permit process seeks to put a 25-acre site off Paul’s Point, near Cedar Tree Neck, in West Tisbury, a 15-acre site off Cape Higgon, off Chilmark; and two sites of 25 acres and 10 acres off Aquinnah.

Funding for the permit process for the three sites, $5,000, came from the Martha’s Vineyard Permanent Endowment Fund.

The area needed for the experimental farm next summer is but a fraction of what is being requested through the state and federal permit process. Mr. Karney said establishing the aquaculture sites now is better done with a look to the future; to do it piecemeal would end up being more costly.

Advance funding through the federal grant helps to jump-start the effort. In the first year of the two-year grant, administered through the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, NOAA has set aside $81,308 for a larger project that includes sites off the Rhode Island coast. The Vineyard portion of the contract is $9,624.

In 2010, the grant rises to $133,179, with $22,432 directed to the Vineyard project. “The majority of the money is going to pay for equipment for the two Vineyard farms,” Mr. Karney said.

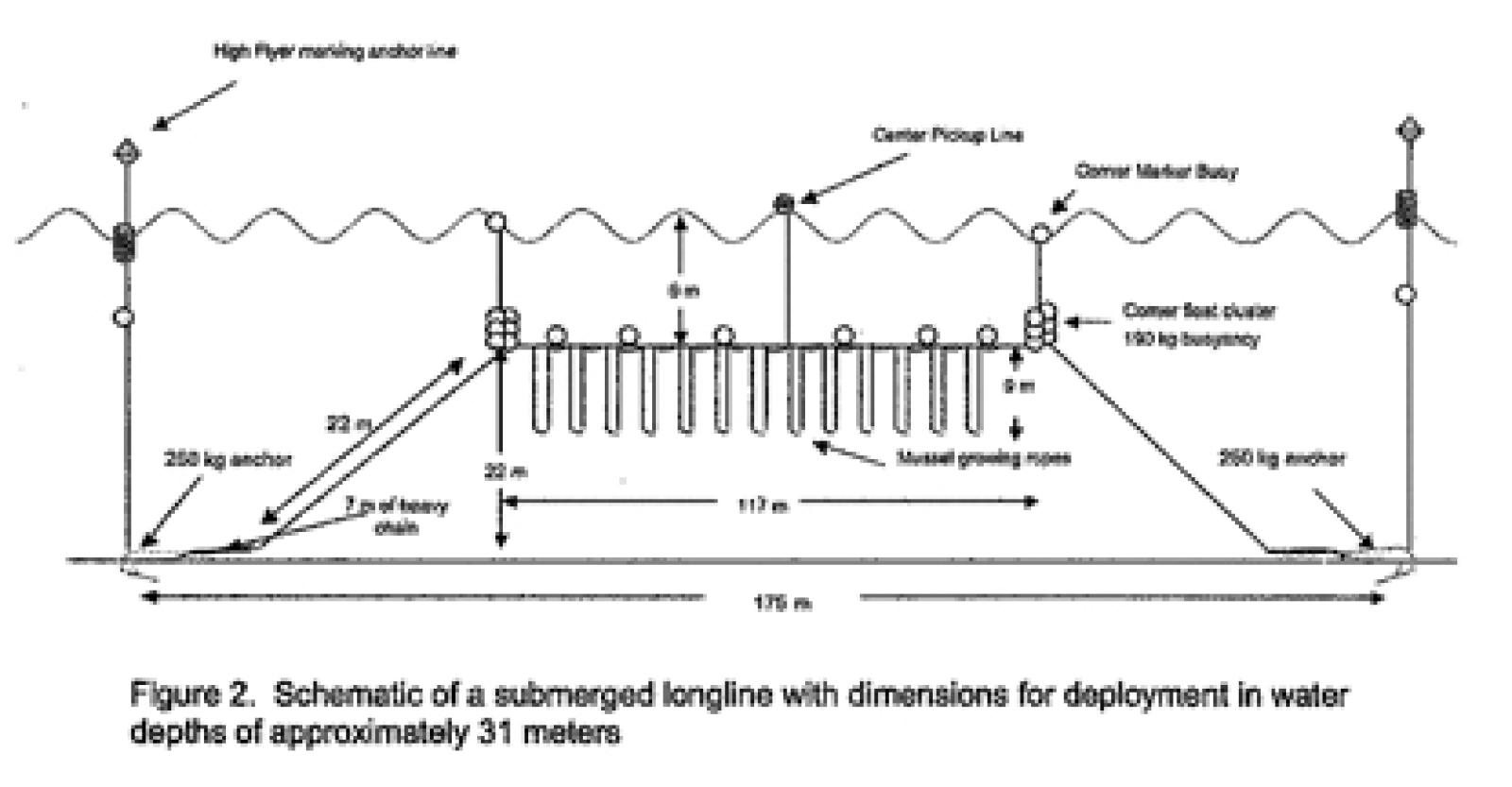

To the offshore boater, the experimental farm is almost all under water. Two well marked buoys, each with a radar reflector dubbed a “high flyer,” will identify the site. Between the buoys there are three smaller buoys. Beneath the markers, 30 feet below the surface, there are mussel-growing ropes which hang down deeper.

There is but one dark side to the experiment. A common crab, called a pea crab, will have a voice on whether the project is a success or not. American seafood consumers don’t like eating mussels with harmless pea crabs in residence in the shell. The pea crabs occur naturally in wild blue mussels. But the question before the scientists and fishermen is whether blue mussels raised on rope lines, off the bottom, will be clear of pea crabs. If they are clear, there will be no problem finding a market for whatever is harvested. A key element to the grant is finding out whether the fishermen can raise blue mussels without the unwanted pea crabs.

Mr. Karney said the future is bright for aquaculture and the shellfish group is a part of it. From 1995 to 1998, the shellfish group was involved in helping to retrain local commercial fishermen on how to raise shellfish. Today there are at least a dozen Vineyarders deriving some income from raising oysters.

Mr. Karney said that what was initiated two years ago by the Chilmark selectmen, specifically Warren Doty, is part of an expanding hope that fishermen will find other ways to make a living by the sea. “There have to be more opportunities for people to work out on the water. There are not enough fish in the wild fishery to maintain the fishing industry. They need a high-volume species like mussels. The Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group has an opportunity to help.

“I think our mission is to preserve and enhance both the wild and the cultured shellfish industry,” Mr. Karney said. “There needs to be a wild component and a private aquaculture component, and we hope to address both of them. By getting involved in the private aquaculture industry, it takes pressure off the public.”

Mr. Karney said: “NOAA has a ten-year plan. They are looking at expansion of aquaculture in the United States. The biggest is shellfish aquaculture. There is general consensus in the environmental community and among aquaculture groups that raising shellfish is efficient and an environmentally friendly form of aquaculture.”

Comments

Comment policy »