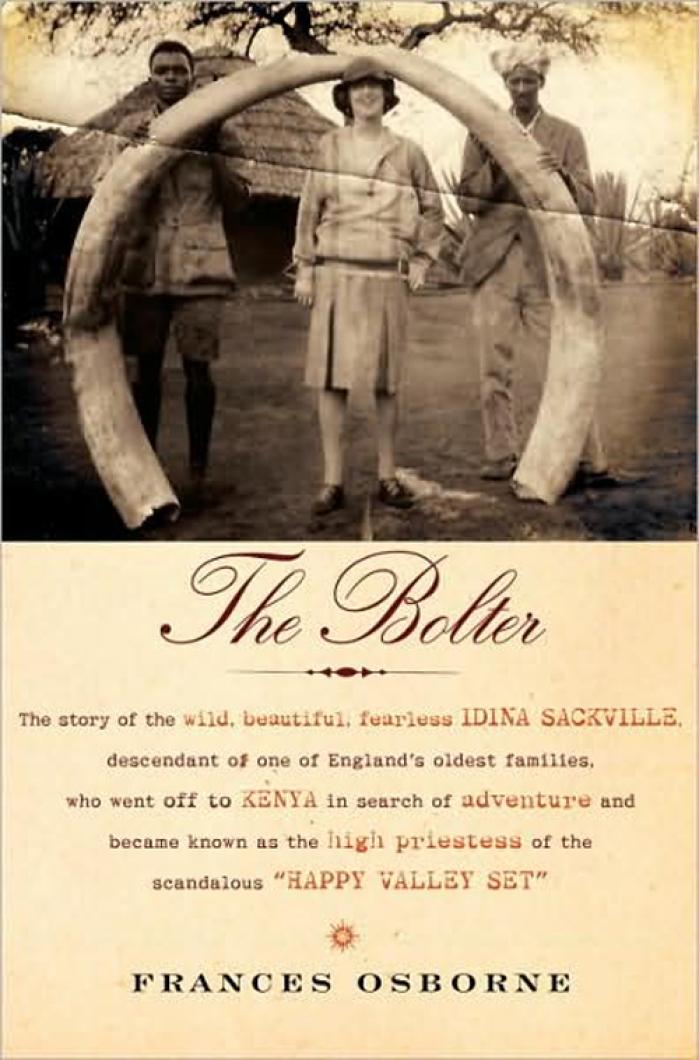

THE BOLTER, by Frances Osborne. Alfred A.Knopf of New York. 283 pages. $30.

Lady Idina Sackville was born in the 1890s to parents who had married for convenience: he for money and she for his title of Earl De La Warr, one of the oldest families in Britain with few achievements to their 800 year-old name but the gift of it to the state of Delaware. The marriage didn’t last.

And so begins Frances Osborne’s biography of her great-grandmother, The Bolter. It is a laundry list of marriages and divorces, with the spaces between “I do” and the decree nisi filled with a dizzying number of bed-partners, not only those of Idina’s but of the family and friends surrounding her.

Simply keeping track of the color and cut of the various wedding outfits is tiring, and as for the never-ending sex, and the drugs (morphine and cocaine) and the alcohol (gin and whiskey for drinking and champagne for bathing) and the fast cars and fast horses and faster women and the public horse-whipping and an attempted murder and a successful one, the several suicides, and the large flowered mirror above the bed (the better to appreciate all those positions), well, prepare yourself for complete exhaustion — and no doubt the movie that will soon follow.

Idina was glamourous, rather than beautiful; sexual, rather than smart. By her own description she was virtually chinless, “a shotaway chin,” but her big blue eyes overcame that unfortunate loss. She knew how to dress and how to wear those clothes on her delicate frame. And, as she was prone to welcoming guests from the depths of her bath so as to allow her the opportunity to dress for dinner in front of them, it’s a fair guess, chin aside, that her frame was very well-formed.

In the world of these self-obsessed, careless people who partied through a depression and two world wars, the only trust that could not be violated was the inheritance trust; retention of ownership was the first commandment. Produce two genetically-approved sons (a spare and an heir) and it was off to the adultery races. So once Idina, at the age of 25, had filled her quota she was eligible to indulge in that sport of kings and aristocrats in which favorite fillies were married and therefore a safer bet.

Let us pass swiftly, as Idina did, over the husbands: Number one is a cavalry officer: rich, handsome and a snoring bore (though tellingly, not to Idina). His best friend (later to become head of British Intelligence) and his batman (considered to be the inspiration for P.G. Wodhouse’s Wooster) promise to be, as do so many of the background characters in this biography, far more interesting than the main players. When her husband’s adultery dance card becomes full to overflowing, Idina, despite his pleas for her to stay, bolts with her “serious” lover. He becomes husband number two, but weakened by the heat of Kenya (the place to which they run) and Idina’s libido (he later described her as a nymphomaniac) this marriage is quickly over. Number three is titled, handsome and eight years younger but shortly after exits through the wide door of their open marriage in pursuit of another. Husband number four comes and goes with a rifle in his hand and many a near miss aimed at any number of Idina’s passing lovers. Husband number five is a pilot and he soon flies away.

One thing Idina learned from her first and third husbands was never to take to her bed, other than to rollick in it. Both good-time boys, they began making their exits while Idina was laid low, first by bronchial illness and later by childbirth. As for the others, if Idina had found it possible to stay faithful she had more than a fighting chance to keep at least one of them by her side. Her final partner was not legally registered. He was a tattooed sailor who presented such a social horror that when Idina visited England and was invited to those houses that would still accept her, he was left behind. Ironically, it was this man who stayed by her side to the end, caring for her in the final years as she suffered from the cancer that killed her at the age of 62.

Is it because these people behaved like children themselves that they so neglected their own? Though Idina’s two boys had spent most of their young lives out of her sight in the charge of nannies, at the ages of three and four she totally abandoned them. Fifteen years passed before she set eyes on her eldest. The reunion took place at Claridges, and for the mother to recognize her son it was necessary that he wore a red carnation. Despite the desperate sadness of this, she still chose that her brother raise her last child and only daughter from her third marriage.

The story picks up pace in Book Two when Idina settles in Africa. Here she is unfettered by others of her “class” who, back in Britain would roundly remonstrate against her lifestyle, perhaps not on moral grounds but certainly on the lack of example she was setting to the middle and working classes.

Once out of the minutiae of family histories and claustrophobic London, Ms. Osborne’s writing broadens and her descriptions of landscapes and skyscapes become evocative; you can feel the morning mists at 8,000 feet, smell the vegetation, and become enveloped in the houses and the gardens that Idina so creatively put together.

Although Idina’s follies and fecklessness are well chronicled, her thoughts on women’s liberation and politics are not offered. Was she a committed suffragette or simply absorbed into her mother’s political world? Her friends swear to her kindness but how did this manifest itself? Was she brave and avant garde or totally sexually driven? We are told she was an avid reader of contemporary novels yet we never learn what she read. Most importantly, how did she feel about the cool abandonment of her children? Idina’s voice, apart from quotations from a handful of letters, is seldom heard and certainly in no depth. Was it that she had little to say?

Perhaps the prospective reader may feel that these days they have heard enough about people in a position of privilege, who spend criminally, bolt on their commitments and indulge in adultery with a spring in their step. However, if there is interest in confirming that history repeats itself you may find The Bolter offers an excellent opportunity to read on.

Frances Osborne discusses The Bolter at 7:30 p.m. on Monday, July 20 at The Bunch of Grapes in Vineyard Haven.

Comments

Comment policy »