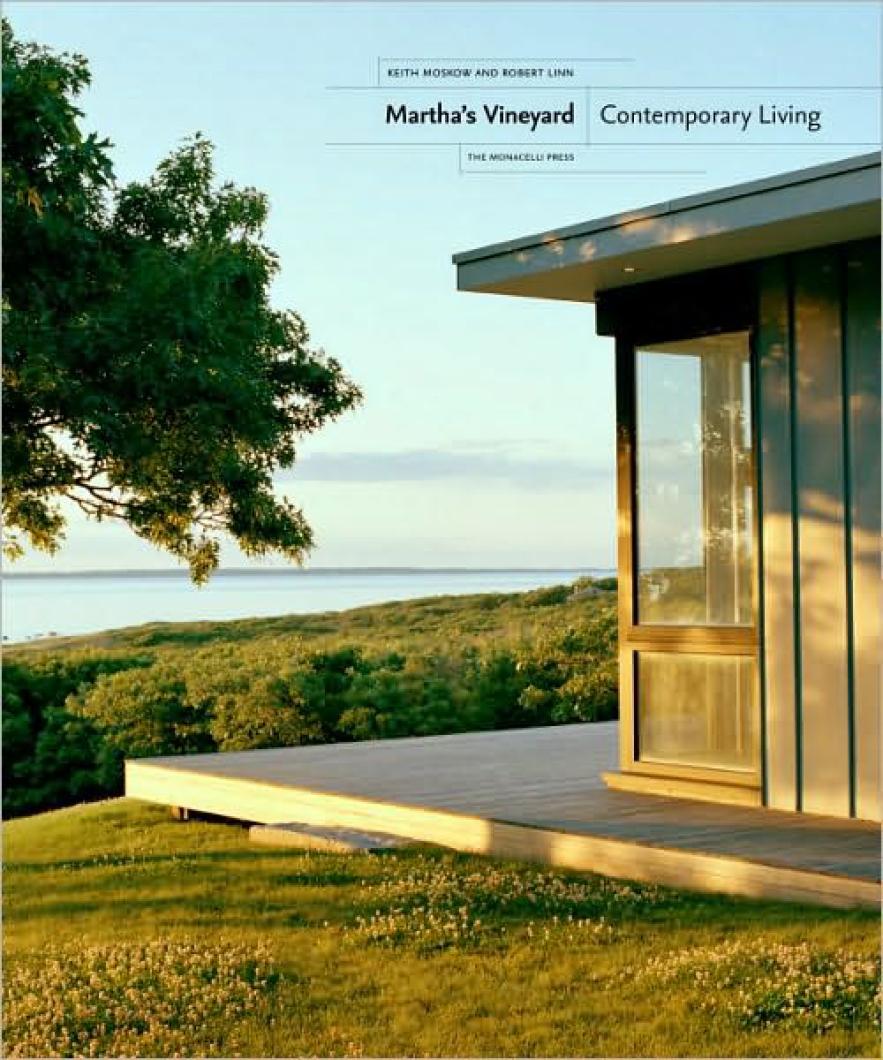

Martha’s Vineyard: Contemporary Living, Keith Moskow and Robert Linn, The Monicelli Press, 224 Pages, $50.

I always approach these architectural pic ture books with trepidation. Most make me jealous. I don’t lust after the houses, but I do envy the passion with which the owners prepare for the photographer’s arrival. The walls have just been painted or recovered, there are no wrinkles in the cushions, and there’s never a stray toy or someone’s socks in the corner. And the flowers — there must be flowers. The implication, of course, is that in addition to having lots of money, the owners in so many ways live better organized lives than I do.

Martha’s Vineyard: Contemporary Living is different. The 25 houses shown, many of which are beautiful, and often quite expensive, really function more as the supporting cast to a vision of the Vineyard itself. It is an ideal Vineyard, but a deeply satisfying one. The houses all stand alone on their own plots — perhaps deck chairs in the foreground, then the gorse and finally the sea. In only one photograph is there a neighboring house and it looks hopelessly ordinary. Many of the houses are shown at twilight. The lights are on and the windows open. A warm summer evening has just begun.

The book also hints at a new epoch on the Island, one in which the land is once again more important than the house, the architect, or the owner. A number of years ago friends insisted I visit with them a newly built house just to get my reaction. It was winter and a time when one could still respectfully explore those parts of the Vineyard unseen during the summer. We traipsed up a lane to see some pipes and a chimney poking up from a small hill. It was only after we walked to the opposite side that I realized that we were looking at a house built into the hill. The front wall was all glass and everything inside was white. The house looked like a bunker for the Strategic Air Command, but it was on Martha’s Vineyard. Perhaps this building could have been more appropriate in the Hamptons where ego and plane-wreck modernism are more the common currency. But not on the Island. There are a number of such houses on Martha’s Vineyard, aching to be seen as “one-onlys,” exploiting the land rather than being part of it, but fewer of these have been built recently. The economy may also have brought us to the tail end of a period of McMansions galore.

Many of the 25 houses, despite their “luxe” have a sense of modesty. They all show an attention to detailing, and the care of the builders who built them. Some to be sure are a bit awkward, several might be just as comfortable in the suburbs of Zurich, and one looks as if it would be happier in the Grand Teton mountains, but these are always the problems when one decides to pick 25, rather than showing just the best. Nevertheless, the predominant theme is of cedar shingles, natural wood and respect for the land.

The past 40 years have been a difficult time for many architects. Schooled as modernists, believing that gable roofs and shingles were signs of middle-class leanings, and having great faith in brushed chrome and white paint, made designing a house on the Vineyard a challenge. This book, I hope, points to a resolution. Rather than ignoring a genre it suggests possibilities within it, and as such is worth having in everyone’s library or even on the coffee table.

Craig Whitaker is an architect and author of Architecture and the American Dream. He owns a home in Vineyard Haven.

Comments

Comment policy »