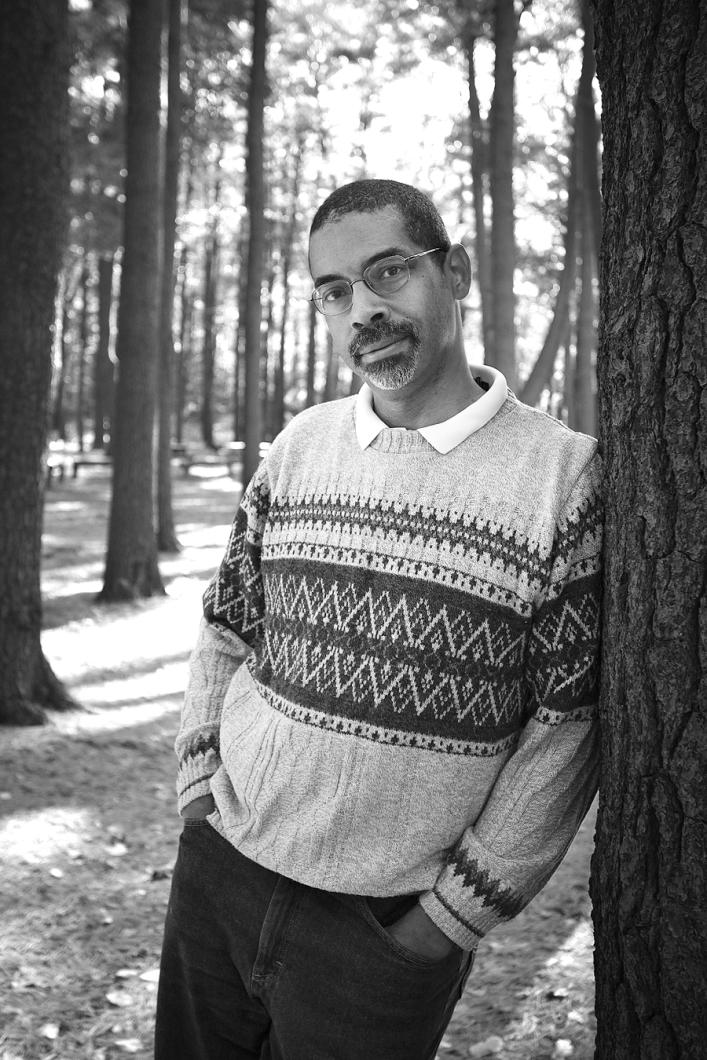

Best-selling author and Yale law professor Stephen Carter deplores those bumper stickers with which people advertise their views on political and social issues.

He’s sorry if that offends anyone, but he really can’t stand them, for a couple of reasons.

First, they are overwhelmingly stuck on the backs of cars; thus they convey the message “Here’s my opinion, I don’t have to look at yours.”

More importantly, though, he objects to them because they are simplistic. They reduce complex issues to “cute little slogans.”

And that, as he said in a lecture at the Vineyard Haven Library on Sunday, is bad for democracy. His reasoning went like this: if a contentious issue could be reduced to a bumper sticker answer, it suggested the solution was obvious, and those who did not accept that obvious, simple answer were “either stupid or evil.”

Thus the bumper sticker phenomenon not only denied the complexity of issues, it denied that reasonable people might differ, and undermined serious debate. The real essence of democracy, he said, was not the right to vote, but the practice of deliberation and debate, conducted in an atmosphere of mutual respect.

And that was increasingly threatened, not only by bumper stickers but by a range of forces from partisan media to the wide, shallow knowledge people access online.

Democracy relied on progressive ideas of inclusion and debate, and was imperilled by the growing trend to “reactionary” sloganeering and “enemies lists.”

The trend, on all sides of political and social debate was a trend toward what one of Mr. Carter’s favorite authors, John le Carre called a “dangerous militant simplicity.”

Which brings us to the central thesis of Mr. Carter’s lecture: Democracy Needs Books. Not just literacy or reading, for in this electronic age people now read more than ever before.

“I’m talking about actual, substantial books that you can hold in your hand,” he said.

Professor Carter now is working on — what else — a new book on the subject. He has published seven previous nonfiction works and four novels, including The Emperor of Ocean Park.

He wanted his audience to know he was not just trying to drum up more business for himself. Nor did he wish to appear too certain of his position about the importance of books to democratic practice. After all, certitude in the absence of full discussion is what he’s against.

What he was working on was “a thesis I’m throwing out for discussion . . . more than a settled view.”

The thing about books was that they signified complexity. They had “heft, weight” and suggested that “ideas need space.”

He cited the motifs of book burning in works like Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 and George Orwell’s 1984. Why did books have to be destroyed?

Because books could betray you by changing your ideas, by awakening the reader’s sense of the complexity of things. The more difficult the book, the more true this was.

“A great work of literature can open our minds to new ways of looking at things,” he said.

Mr. Carter noted worrying trends. The current generation was the first that reads less for pleasure. Politics today worked in ways that did not allow complexity.

And apart from the increasingly-partisan nature of the media people absorb, the very technology of that media worked against deep engagement with specific issues.

He noted research which showed that people who read from a screen rather than a printed page retained as much of what they read but were less likely to have their critical faculties and imaginations engaged by it.

And if there was anything else on the screen, like a news crawl, for example, retention declined. College students had been shown to retain less when they took notes on laptop than when they wrote notes on page.

As for e-books, like the Kindle, well, there just has not been enough study to determine whether they change the way people read and absorb.

He had noticed, over almost 30 years teaching law at Yale, that the students coming to him were “not as good,” notwithstanding the fact that they tended to have higher grade point averages. As a result, he had to spend a great deal more time preparing them to cope with the level of detail required.

He suggested the reason was that they could not maintain focus to the extent of their predecessors, probably because of the constant distractions of the modern wired world.

“All the data about multi-tasking says you can’t do it,” he said. “If you do your law school work while maintaining your Facebook page, you will not do it as well.”

Professor Carter said he now taught legal ethics through the study of books which were not law texts but novels or plays. That was because such literature inspired an understanding of ethical nuance. Even there, though, he had been forced to drop certain texts because they were too dense for the students, so they did not read them or resorted to using condensed notes.

Most of the time in his classes was spent in discussion of the works; then, for maybe 20 minutes at the end, he would lecture on the ethical issue raised.

Physical books had other uses, too. One of the best ways to understand another person was to look at their library, and see which books were well-thumbed and which were there for show.

But even show books had significance. He cited the example of the strange competition that existed among the early Puritan settlers in Massachusetts, to have the biggest, heaviest bible. As though that was the measure of their piety.

The contest seemed silly on the face of it, he said, but on reflection, he figured they were onto something. And that is that books give a “physical weight and volume to ideas.”

He recalled that back in the 1970s, as he was finishing his honors thesis at Stanford, he went one day to get a book from the stacks in the library. He found himself with tears in his eyes, as he looked along rows and rows of shelves. There he was, ready to graduate, and he had read only the tiniest fraction of those books.

“And I wanted to read them all,” he said.

Comments (6)

Comments

Comment policy »