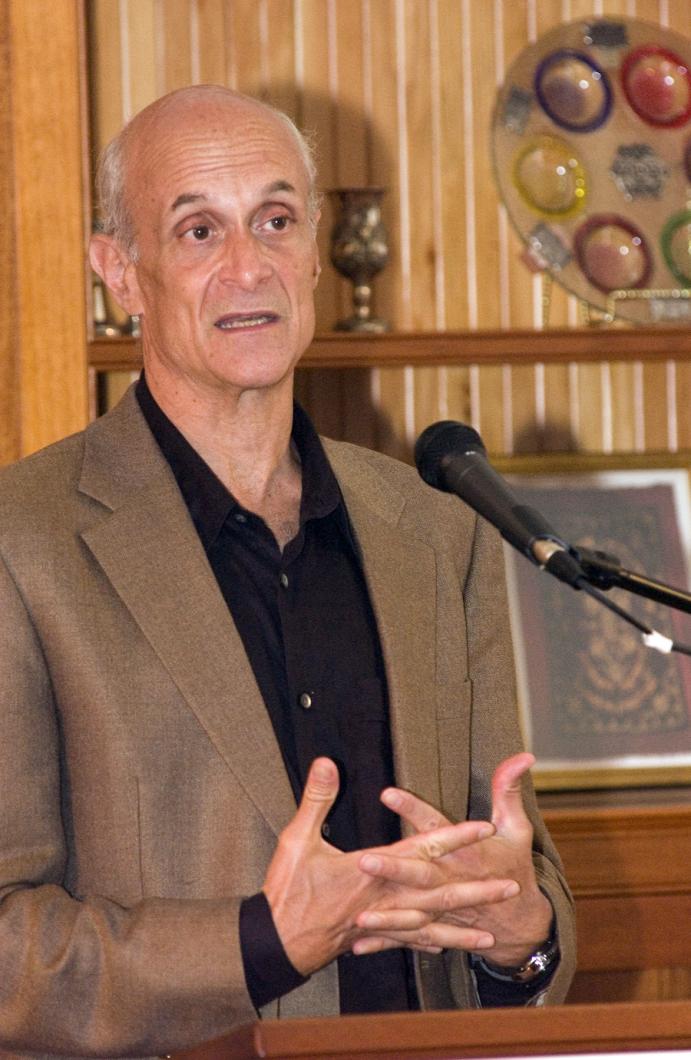

A tranquil summer evening in Vineyard Haven may have seemed a strange place for a spine-chilling appraisal of the nation’s security gaps, but on Thursday night at the Martha’s Vineyard Hebrew Center former Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff sounded a bleak and vigilant tone, warning that we have entered into a new world and our concept of security must change accordingly.

The old world was a binary one where violent acts were neatly divided as either criminal or military. In the old world the United States was equipped to respond appropriately to such threats, with law enforcement and the judiciary responding to criminal acts and the military and intelligence agencies handling threats from abroad. Now we face more nebulous dangers, what Mr. Chertoff terms “quantum security problems,” where those who wish us ill can act in ways that are simultaneously criminal and inescapably warlike. How we respond to such aggressors was the topic of Mr. Chertoff’s talk.

“You could have an individual that we could encounter as a member of Al-Qaeda or the Taliban in some region of Afghanistan, and I don’t think we have any difficulty understanding that we could drop a bomb on him and kill him,” Mr. Chertoff said. “But if the same person is walking along the streets of New York planning to plant a bomb in the city could we do the same thing?”

It is unclear whether Mr. Chertoff sought such sweeping powers but he noted that the country had already done much in the way of hampering terrorist networks with its foreign policy. The invasion of Afghanistan, he contended, came as a major surprise to Al-Qaeda, which had formerly acted from the region with impunity, and helped to disrupt and destroy a sophisticated network of camps.

There still remains a slew of failed or failing states, “ungoverned space” Mr. Chertoff called it, where lawlessness prevails. From these festering wastelands, such as Yemen and Somalia, nefarious agents plot the next major attack.

“It is imperative for us to create order where there is disorder,” Mr. Chertoff said. “Nine-eleven showed us that dealing with these areas is not optional.”

Afghanistan is in many ways still primarily a swath of ungoverned space, particularly in the area surrounding its southern border with Pakistan known as Pashtunistan. With such volatility on either side of the border and Pakistan an unpredictable nuclear power, Mr. Chertoff stressed the importance of commitment to the region.

“The hardest thing for Americans is patience,” he said. “The other side can nurse a grudge for 600 years.”

Even with a sustained commitment in southern Asia, Mr. Chertoff said the threat is far more diffuse than any one country or series of countries. With the Internet, organizations like Al-Qaeda, with satellites as far afield as Somalia, Mali and Indonesia, can wage war with the sophistication and coordination once reserved only for nation states.

He has settled on the appellation “violent radical Islamists” for the enemies of civilization, a title he understands invites criticism for singling out one religion. But he argues that the cause of Al-Qaeda is couched in explicitly religious terms and to deny the religious dimension of extremist thought would be not to fully appreciate the problem. He compared it to the Mafia trials in the 1980s when Mario Cuomo accused then-U.S. Attorney Rudy Giuliani of fearmongering and defamation in addressing Italian-American organized crime, contending that the Mafia didn’t exist. When tapes surfaced of mob bosses referring to their organizations as the Cosa Nostra, it became clear that it was an Italian problem.

As former head of the Department of Homeland Security under the Bush administration, Mr. Chertoff defended the organization’s steps regarding airport security, a topic about which almost everyone in attendance registered some complaint. Rather than being endlessly behind the curve dictating increasingly peculiar rules and regulations about carry-ons and shoes, Mr. Chertoff claimed that the increasingly stringent rules have saved hundreds of American lives. Rather than carrying liquid explosives onto the plane, or an even simpler briefcase bomb, the Christmas Day so-called underpants bomber was forced to contrive an excessively complicated bomb that had little chance of success from the get-go. It was, Mr. Chertoff said, “a forced error” brought about by the new, stricter rules. The same applied, he said, to the Times Square bomber, who used inferior materials to build his unsuccessful bomb as a result of improved intelligence gathering techniques that would have instantly implicated him had he bought large amounts of higher grade explosives.

There is still much more work to do, said Mr. Chertoff, who estimated that the chance of a major biological attack in this country in the next 10 years is “very likely.” He is especially fond of Cipro, the antidote to anthrax, and came close to calling for nationwide federal distribution of the drug. He is also deeply worried about cyber attacks on the nation’s infrastructure. As society grows increasingly dependent on computers for everything from air traffic control to banking, Mr. Chertoff said, it grows increasingly vulnerable.

The theme of the evening was persistence. Responding to groans in the audience at the seemingly endless prospect of war, Mr. Chertoff called attention to the plight of the people inhabiting the desolate outposts we occupy.

“If we pull out of Afghanistan tomorrow, every woman who tried to learn the past few years is dead,” he said. “Every person that taught that woman will be killed.”

Pressed by the audience to predict an eventual conclusion to the endless peripheral skirmishes in failed states, Mr. Chertoff dropped his guard for a moment of chilling honesty: “Sometimes it doesn’t end.”

Comments

Comment policy »