By MEGAN DOOLEY

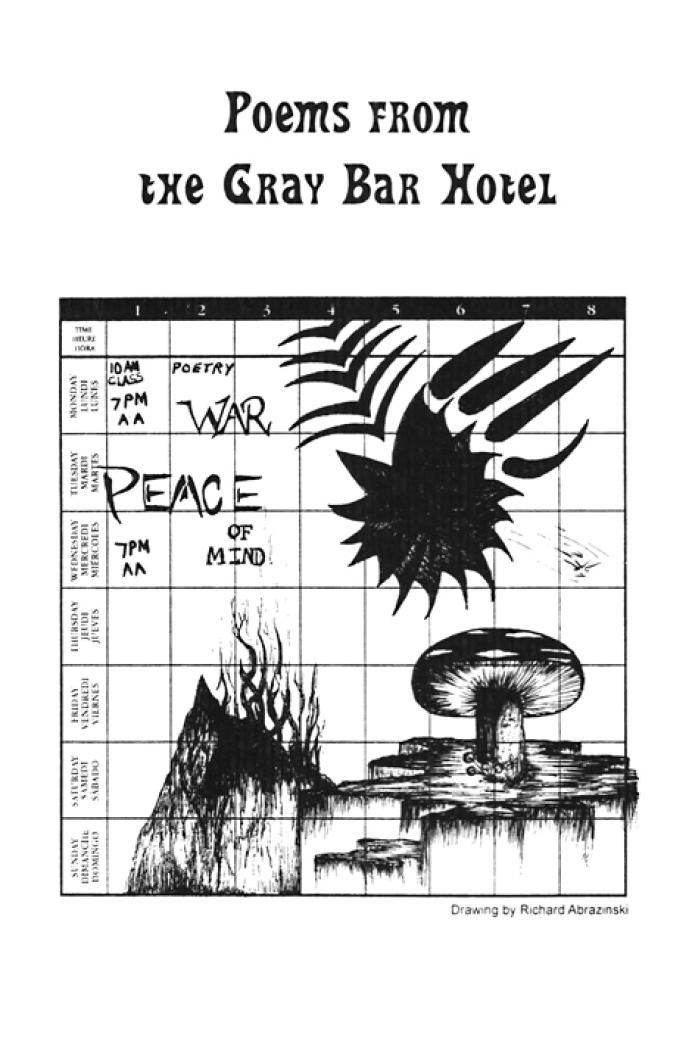

The book is called Poems from the Gray Bar Hotel. The title refers to the nickname that inmates have given to the Edgartown House of Correction, where West Tisbury poet laureate Fan Ogilvie held poetry classes last winter. But Mrs. Ogilvie said the jail is more like a revolving door for prisoners with haunted pasts who often can’t seem to get out of their own way.

“There’s a lot of recidivism, where they get out, they can’t figure it out, and they come back,” said Mrs. Ogilvie this week. “They don’t like it, it’s not a pleasant place to be.” But it becomes familiar, even comfortable, and the cycle ensues. “They don’t know how to get out of the cycle . . . until they can figure something out for themselves, that’s the best thing that they have. That’s the only thing they have,” she said.

She is no savior. Many of her students had little formal education, no experience reading or writing poetry, and no interest in the endeavor. So she concentrated on exposure to some classic poets, including Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman. “We always used a poem to start. We always read a poem. I never tailored it just for their education level, which I could kind of gauge, because I’ve taught so much,” said Mrs. Ogilvie. “I would just use really, really good poems that have a theme that they could understand and write from.”

Mrs. Ogilvie first became interested in teaching prison courses in the 1970s. A friend was teaching at a women’s prison in New Haven, and she asked for the opportunity to take on a course of her own. The plan fell through, but she held onto the hope of teaching inmates through decades of teaching outside of prison walls. Then more recently she bumped into Katy Upson, the education facilitator at the county jail here. The two women worked out a plan for Mrs. Ogilvie finally to teach in the setting she had wanted. “It’s basically kind of an old dream, like a 30-year dream,” she said.

Mrs. Ogilvie said she learned a lot herself in those poetry sessions. She would usually set aside 20 to 30 minutes of the hour-and-a-half class time for the students just to write. Then she would ask that they finish up by the next week’s class. “I learned they don’t have any kind of peace or time alone or downtime to be able to write,” she said.

The poems inside Gray Bar Hotel represent a firsthand, fearless glimpse into the experiences of theses inmates. It’s not always pretty; Mrs. Ogilvie said the book was edited for content, and some material was too sensitive or controversial for publication. But it is honest.

The topics covered are what you might expect from any poet: Love, loss, pain, and of course, captivity.

“I feel forgotten like two-year-old shoes in the back of the closet, or like a week-old tray of food still rotting in the refrigerator. People I held close to me are the farthest from me now. No letters, not one thing that shows I’m still on their mind, or shows that I still exist to them,” wrote an inmate named Demetrio, whose biography at the front of the book reads simply: “Writer extraordinaire.”

“Being caught in a lens, being caught up, caught in a situation, caught up in your own mind, looking for a way out, not always an escape, caught by the look in her eye, the sound of her voice, caught by the seduction of, escaping reality,” wrote Richard, in a poem titled Caught Up.

“Captivity is my enemy, I long for freedom of light. I hear the cell door slam into the night. Captivity, the stranger so close. Freedom, the friend so far away,” wrote an inmate named Ric in My Enemy.

“They write what they feel. They write from the heart. They’re very honest,” said Mrs. Ogilvie about the poets. She said from the beginning, she hoped that the class would come together, respect one another and take the work seriously. They did that, and it paid off with a collection of poetry that gave each inmate poet something to feel proud of.

The work produced also offers insight into the lives of a group of men who seem perpetually stuck in a cycle of drugs, violence, and crime. “Katy very wisely said, ‘You know, Fan, a lot of these guys have been victims as well,’” said Mrs. Ogilvie. They’ve suffered childhood abuse, parental negligence, poverty and drug abuse. “Who knows when the violence started,” she said.

Mrs. Ogilvie said she began to feel better and better each time she left the prison after teaching that week’s class. “I came out pretty high every time I’d been with them,” she said, adding that it was the best class she could remember in her 25 years of teaching. “Yeah, because we’re your captive audience,” Mrs. Ogilvie said one student joked when she told the class of her preference.

The project culminated in a celebration and open reading where the writers were invited to share their work with other inmates, selected jail employees and a special guest. Writer and teacher Judith Tannenbaum, the author of Disguised as a Poem: My Years Teaching Poetry at San Quentin, came to hear the stories of inmates from a little-known jail on Martha’s Vineyard.

“They washed up and they got the nicest clothes they had,” said Mrs. Ogilvie. “They were just so proud of themselves, you could just tell.”

Comments

Comment policy »