In the effort to develop wind energy in the ocean between Block Island and Aquinnah, Massachusetts will follow the lead of the Ocean State.

In July Massachusetts and Rhode Island signed a memorandum of understanding about the possibility of jointly developing wind energy in federal waters between Rhode Island and Massachusetts. At a meeting at the regional high school last Thursday, Grover Fugate, executive director of the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council, announced that although the two states would share in the economic cost and benefit of any offshore wind projects, Rhode Island would take the lead in the development process. Mr. Fugate outlined an ongoing three-year, more than $7 million effort on the part of his state to locate appropriate sites for wind farms in a presentation that drew sharp contrasts with the Massachusetts Oceans Management Plan presented a year ago.

To Islanders still stinging from the Massachusetts siting process, widely perceived as indifferent to Vineyard concerns, the news came as a relief.

At Thursday’s meeting Deerin Babb-Brott of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EOEA) outlined the state’s 12-step environmental review process going forward and asserted that the state’s task force, a group that includes local officials, tribal representatives and planning boards such as the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, would be involved in each step of the process.

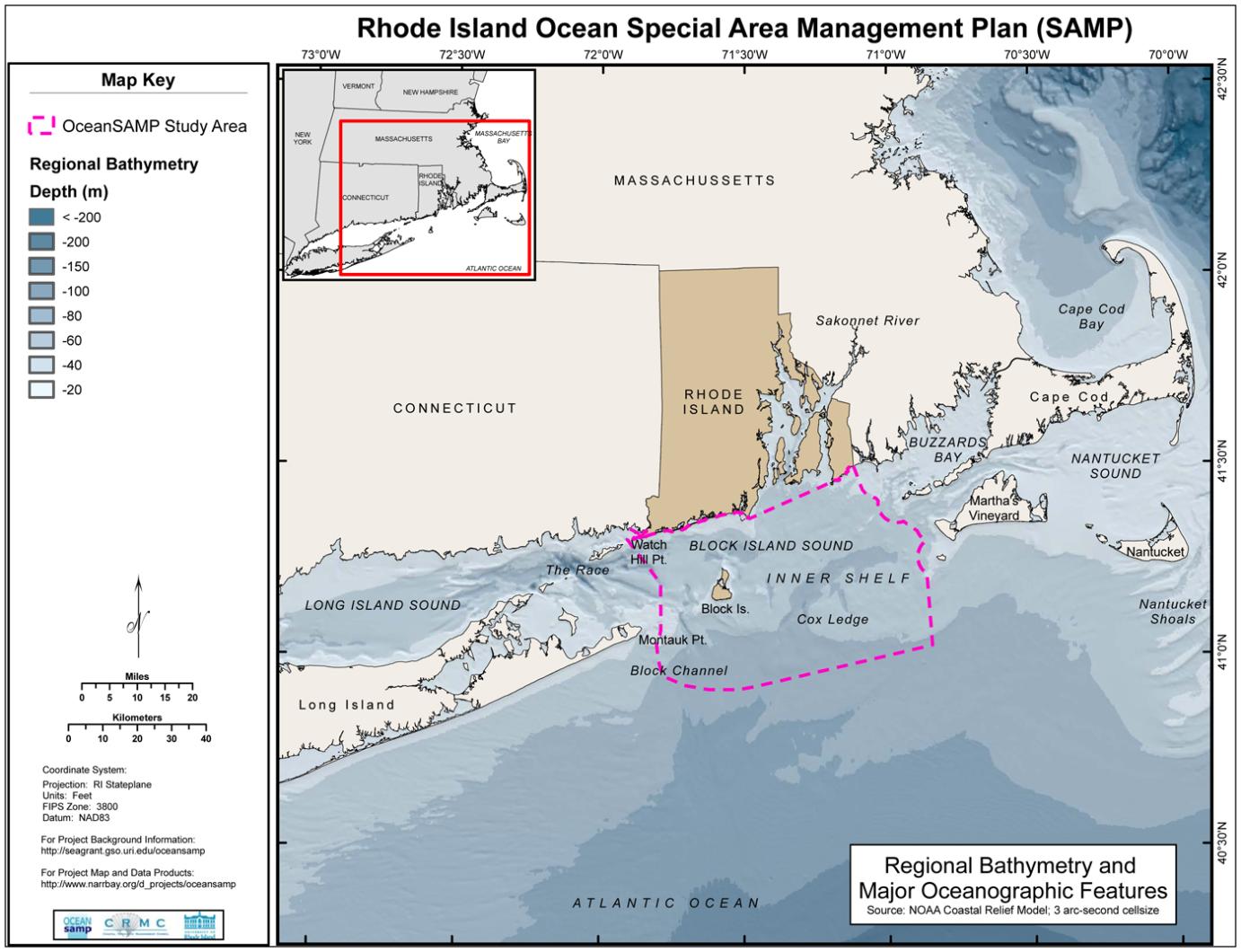

That announcement was eclipsed however, by Mr. Fugate who dazzled the audience with the results of his state’s sweeping study of local waters, presenting maps layered with data about everything from popular shark cage diving areas to submerged and culturally significant prehistoric lands. Some areas, such as those that overlapped with data points compiled from a classified database of right whale and sea turtle migration, were ruled out automatically, as was any development in less than 20 metres of water, as it could interfere with the livelihood of diving duck populations. Shipping lanes, commercial and recreational fishing grounds, the presence of unexploded ordnance and even the geology and rugosity, or roughness, of the ocean bottom — predictive of fertile fish rearing areas — disqualified or discouraged development in large sections of the proposed area.

To amass the trove of data, Mr. Fugate’s department teamed with the University of Rhode Island, employing graduate students, university scientists and legal experts.

“There was very little data when we started out,” he said. “We were originally given $3.2 million, which is not a lot of money for research like this and it disappeared very quickly. The platforms we were using to do geophysical work alone cost $20,000 a day.”

The impetus for the well-funded project, Mr. Fugate said, was the state’s recognition that climate change would significantly affect its population which both depends on the ocean and crowds the tiny state’s more than 400 miles of coastline. He said Rhode Island has already seen the incipient effects of climate change, as demersal fisheries have replaced pelagic ones and Narragansett Bay has come to resemble more of a Mid-Atlantic estuary over the decades.

“Twenty-eight per cent of coastal states account for nearly 80 per cent of the country’s energy use,” he said. “It’s a coastal-derived problem. It makes sense on our part to address that with the tremendous wind resources off the Atlantic coast that offer a significant potential to displace fossil based fuels right now.”

After the presentation audience members pressed Mr. Babb-Brott about the disparity in rigor between the siting process in Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

Mr. Babb-Brott said his team was only given a year pick to prospective sites and had to rely on existing data.

“We would have loved to have had the time and the resources that Grover and his team had to apply to this,” he said. He also said the state’s attention has turned mostly to development in federal waters as the Martha’s Vineyard Commission will be responsible for determining the scale of development in the contentious state waters off of Noman’s, as would Cuttyhunk, which is currently in talks with the EOEA.

And Mr. Fugate defended Massachusetts too, arguing that it is still in early days of wind regulation.

“Rhode Island and Massachusetts are light years ahead of everyone else in the U.S. in terms of this kind of planning work,” he said. “We are advancing this whole planning concept beyond anything that’s ever been done before. We didn’t have a road map at the beginning of this.”

To Vineyard fisherman Bill Alwardt, the two states’ designs on federal waters represented still another slight to an already devastated fishing industry.

“All I see is we’re losing ground,” he said in an impassioned speech to Mr. Fugate and Mr. Babb-Brott. “Why are you picking on the fisherman? All I see is Martha’s Vineyard being picked on.”

Mr. Fugate said commercial fishing presents problems that would have to be resolved but that the states were looking into sites with minimal impact. In addition, he said the windmills would act as artificial reefs that would attract fish and said that he is in talks with the Coast Guard and developers about the possibility of rigging some towers to allow recreational boaters to tie up to them.

Warren Doty of the Martha’s Vineyard/Dukes County Fishermen’s Association was encouraged. “The Rhode Island plan you presented tonight is extremely impressive,” he said.

The forum at the high school came a week after state and federal officials announced that they had agreed to push development in the federal waters south of the Vineyard from nine miles to at least 12 miles offshore and almost entirely off of the Nantucket Shoals. That announcement was welcomed by town officials who have witnessed a softer approach from government wind planners of late.

“I’m getting really encouraged,” said Oak Bluffs selectmen Kathy Burton at a recent selectman’s meeting. “They actually listened to us and restudied the fisheries. Unfortunately this doesn’t affect Cape Wind because it has already been approved.”

A more comprehensive account of Rhode Island’s efforts can be found at seagrant.gso.uri.edu/oceansamp/.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »