When the Civil War began a century and a half ago the Vineyard was decidedly pro-Union, but ever since there has remained one prominent Vineyarder whose allegiance to The Cause has been suspect. He greets many thousands of visitors yearly from his Ocean Park pedestal and his original foot will be on display next Saturday when the Martha’s Vineyard Museum unveils its exhibit We Are Marching Along: Martha’s Vineyard and the Civil War.

“Our guy is a Union guy,” assistant curator Anna Carringer said definitively about the Oak Bluffs Civil War soldier memorial. “It was mistakenly painted the wrong color and money that was put into building it was put up by a Confederate veteran who was living on the Vineyard after the war, so I think that’s attached itself to the story.”

Seven score and ten years ago on April 12 Confederate forces began their bombardment of Fort Sumter. The Vineyard was wary of the South’s naval ambitions.

“In the beginning there was a lot of fear about being vulnerable to attack,” said Ms. Carringer. “Right from the start Vineyarders were trying to raise money to get protection, to get armed and get uniforms for the home guard.”

Luckily the Vineyard avoided invasion but its sons and daughters did not escape the worst of the brutal conflict. Compiled from reports and editorials published in the Gazette and letters home from Vineyard soldiers, as well as items from the museum’s vast collection, the exhibit offers a rare look at the Island’s relationship with a war that although remote was still acutely experienced offshore. Patriotism ran high on the Island and Gazette editor and founder Edgar Marchant, though a Democrat not necessarily moved by the arguments of abolition, proved himself a Union firebrand.

“You should read some of the stuff that he’s writing at the beginning,” said Ms. Carringer. “He’s like ‘hang those secessionists! Let’s throw them in the ocean and let the sharks eat them!’”

“And the sharks aren’t going to want to eat them because they’re so horrible!” added museum curator Bonnie Stacy, channeling Mr. Marchant’s indignation.

Vineyarders who left the Island for the front lines endured endless marches, the perils of 19th century medicine and that most intractable malady, homesickness.

“A man can’t get along and grow very fat on government rations alone,” wrote union soldier and future Gazette owner-editor Charles Macreading Vincent. “Especially when he has a delicate appetite and is so situated that he is deprived of the staff of life, that is to say, herring.”

Luckily for Mr. Vincent and his fellow Islanders abroad there was a corps of devoted Island supporters that labored to make life easier for the Union soldier.

“There was definitely a lot of patriotism, especially on the part of the women,” said Ms. Carringer. “They knitted blankets, stockings and underwear and sent boxes to the soldiers and founded a number of ladies’ soldiers’ relief societies.”

Mr. Vincent was also consoled by the unlikely sight of a beloved Vineyard-New Bedford ferry, the Monohansset, at port in South Carolina where it had been rented by the government for use as a dispatch transport. The sight of the ship, a painting of which is displayed in the exhibit, Mr. Vincent wrote “was good for sore eyes.”

In many ways life continued as normal on-Island with camp meetings and the agricultural fair carrying on unaffected. In the Gazette, blithe recommendations on hen-keeping from Nancy Luce would appear next to the reports from the distant southern theatre.

Vineyarders shared in the unrealistic expectations of their fellow countrymen who predicted a brief if mildly unpleasant war.

“If you read the editorials and especially at the beginning it’s like, it’s summer, let’s go to the beach and put all of this hostility behind us,” said Ms. Stacy. “The war’s almost over, southern people, why don’t you come up and vacation here.”

Closer to the battlefield, though, the gruesome reality of combat was plain. Most unsettling in the museum exhibit is a medic’s kit, filled with rusting and invariably sharp metal tools, from bone saws to trepanning devices at a time when anaesthesia was grimly unsophisticated. The Vineyard’s Elisha Smith who survived the abattoirs of Antietam and Gettysburg, having been shot in both battles, succumbed eventually to tetanus at a hospital and died.

Other records of Island soldiers are agonizingly incomplete. A 15-year-old Wampanoag boy named Alfred Rose enlisted in May of 1864 and was dead by July, cut down during the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Va.

“We don’t know much about him except that he was from Gay Head and he died,” said Ms. Stacy.

Also featured in the exhibit are the exploits of former whaling captain and naval man Thomas Peakes, who was captured by Confederates, a wardrobe of gray and blue uniforms for children to try on, and newspaper excerpts and broadsides that capture the local outcry over conscription practices in the commonwealth where the quota for soldiers took a toll on an Island where a third of its able-bodied men were either at sea whaling or already serving in the Navy.

“[Conscription] is such a small part of the grand story of the Civil War but for the Vineyard it was huge,” said Ms. Carringer. “It took up a lot of editorial space in the Gazette. So the exhibit shows that for people here on the Vineyard, as is true through all major events in history, we experience them in a much different way.”

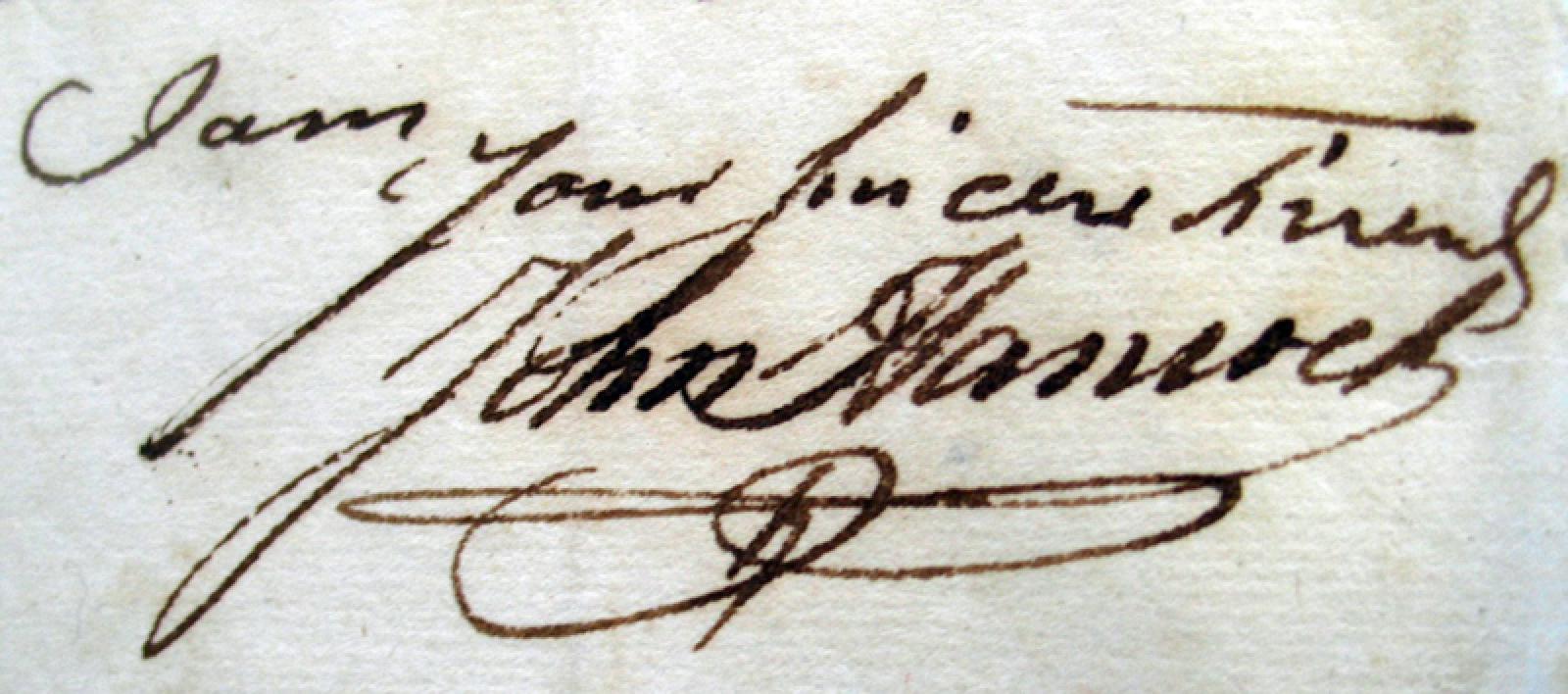

Also this weekend the museum will be opening what will become a revolving exhibit called Spotlight, which will feature some of the more miscellaneous but no less fascinating artifacts from its collection. The exhibit includes two stuffed heath hens from the museum’s veritable roost of the taxidermied specimens in storage, a letter to Tisbury’s James Athearn from John Hancock and the pulpit from the Bradley Memorial Church, which sports two distinctive hand-shaped impressions at either corner of the podium.

“Unfortunately we don’t have pictures of Rev. Oscar Denniston actually preaching but when we pulled this out to exhibit it we noticed these corners that were very rubbed down,” Ms. Stacy said, referring to marks left by the pastor of the Island’s first African American church. “We can just picture him there standing and preaching. I don’t know why else that would be worn that way.”

The opening and reception for both exhibits will take place tomorrow, April 23, from 3 to 5 p.m. at the museum. Admission is free to members and $7 for nonmembers.

Comments

Comment policy »